In a landmark move that adds wind to the sails of indigenous struggles to protect sacred lands everywhere, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has passed a resolution declaring that all protected areas and the sacred lands of Indigenous Peoples should be ‘No-Go Areas’ for destructive industrial activities like mining, dam-building and logging.

Motion 26 was passed during last week’s World Conservation Congress; a quadrennial event that brought together almost 9,000 government officials, scientists, business leaders, academics, indigenous representatives and civil society groups in Hawai’i to set the global conservation agenda.

The Motion urges governments to “respect all categories of IUCN protected areas as No-Go Areas for environmentally damaging industrial-scale activities and infrastructure development.” It also calls on businesses to “withdraw from exploration or activities in these areas, and not to conduct future activities in protected areas.”

The Motion’s success marks only the second time in history that the IUCN, the world’s largest conservation organization, has taken a sweeping global stand to protect nature from mining and other extractive industries. And this major precedent owes much to Indigenous Peoples.

As hundreds of indigenous nations gathered in a stunning alliance at Standing Rock last week, another diverse group of indigenous sacred site custodians made the trip to Honolulu. There they raised awareness of the critical importance of sacred lands in struggles to safeguard indigenous rights, protect nature and prevent runaway climate change.

Thanks to the work of these custodians and civil society allies, Motion 26, which had attracted significant opposition from within IUCN’s business membership before the Congress, passed almost unanimously.

Supported by the IUCN Council, the highest elected advisory body in the IUCN, the motion also got Yes votes from the governments of Russia, China and Canada. The USA abstained and Australia and South Africa both voted No to the motion.

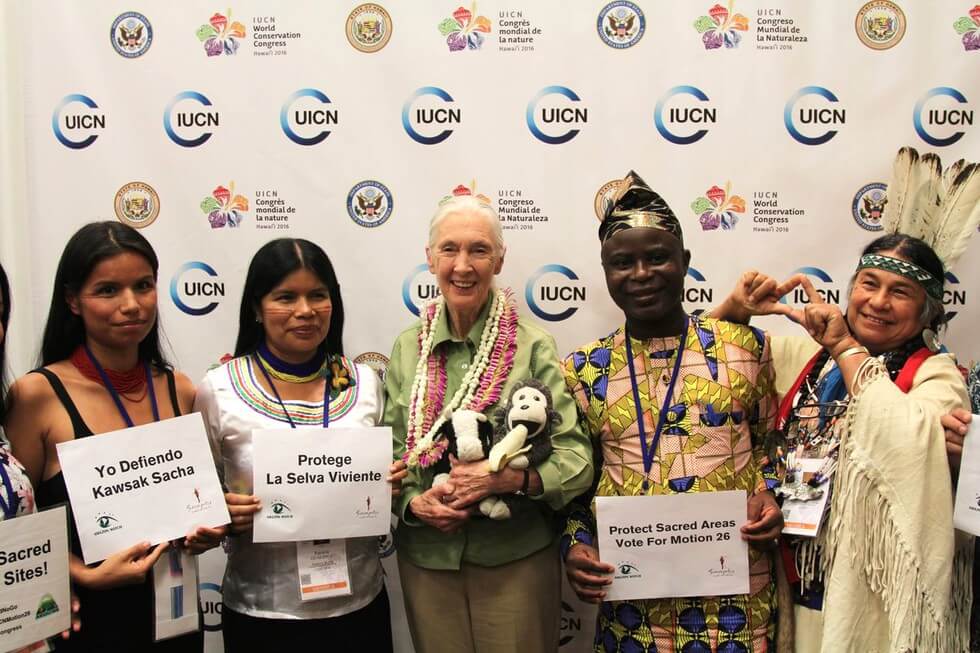

At the World Conservation Congress, the indigenous delegation supporting Motion 26, made up of representatives from the U’wa People of Colombia, the Kichwa of Sarayaku, Ecuador, Winnemem Wintu, US, Gabbra herdsmen, Kenya and others from Benin, Papua New Guinea, Russia and Mongolia, released a powerful statement that highlights the complex existential relationship between sacred lands and Indigenous Peoples, and their importance for conservation.

In their Statement of Indigenous Kahu’Aina Guardians of Sacred Lands, the custodians describe a united understanding of sacred natural sites as natural places, such as mountains and springs, which are “nodal points, responsible for the harmonious and healthy functioning of Mother Earth.”

As places where profound spiritual energy and knowledge are held, the custodians say that sacred sites are crucial to the transmission of indigenous knowledge and ecologically attuned governance systems down the generations.

The cultural and physical survival of Indigenous Peoples, and therefore the realization of their rights under the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, is contingent on the continued existence and health of sacred lands, say the custodians.

Failure to heed this message and recognize the existential connections between Indigenous Peoples, their cultures and their lands will lead to further failures to protect nature and combat climate change, says UN Special Rapporteur on Indigenous Rights Vicki Tauli-Corpuz.

“Conservation organizations often fail to take into account why the forests are still standing. Often it is the indigenous people who have lived there since time immemorial who protected and preserved these lands … indigenous people and local communities are the best proven stewards of their traditional lands and resources, and respecting their rights is critical amid the climate crisis”, says Corpuz, whose statement is backed up by recent research.

At sessions throughout the Congress, the delegation of Indigenous custodians highlighted how extractive industries disproportionately affect Indigenous Peoples due to their umbilical connection to sacred lands.

Aura Tegria, a member of the U’wa Tribe from Colombia, described how threats to Mount Zizuma, a sacred site for the U’wa, are affecting her people.

The presence of energy mining projects within U’wa territory accelerate climate change and violate our mandate to protect, take care of and safeguard our Mother Earth, carrying us toward a physical and cultural extermination.

Hundreds of other indigenous communities around the world have similar stories to tell—many of which have been covered by IC—but the true depth of the impacts are rarely understood by non-indigenous peoples.

In their statement, the custodians powerfully translate the realities for all audiences, describing “industrial activities in all their manifestations – mining, oil and gas extraction, dams, logging, corporate agricultural expansion, industrial-scale wind and solar power, and other extractive practices” as responsible for “multi-generational psychological and emotional trauma for indigenous communities.”

Indigenous sacred site custodians with Dr Jane Goodall

This trauma is spreading globally, as demand for commodities—from fossil fuels to palm oil and timber—intensifies the threat that extractive industries pose to sacred lands and protected areas.

Earlier this year, a WWF report revealed that over half of all natural World Heritage Sites (114 of 229), supposedly the most zealously protected areas in the world, are under threat from mining and other destructive industrial activities.

This pattern is replicated in the lands and sacred sites of Indigenous Peoples, which are increasingly seen as areas of untapped economic potential by mining, logging and dam building companies, amongst others.

Recent research by environmental think tank, Global Witness, has revealed that indigenous communities suffer disproportionate levels of physical, as well as cultural and spiritual, violence as they honor their obligations to defend their lands. The group found that in 2015, of 185-recorded killings of environmental defenders, 40% of the victims were indigenous.

In 2003, at the IUCN World Conservation Congress in Durban, the world’s largest conservation organizations pledged to respect the rights of Indigenous Peoples to their lands as part of a ‘new paradigm’ for conservation.

It was hoped this would be a turning point for indigenous rights after more than a century of oppression, in which conservation was carried out with the aim of vacating landscapes of Indigenous Peoples through mass dispossessions and violence.

Yet, thirteen years on from Durban, Indigenous Peoples around the world continue to be evicted from their traditional lands and denied their rights to make way for conservation initiatives, whilst mining companies and other industries move in.

In the Congo Basin, the creation of at least 26 of 34 protected areas involved displacing the Indigenous Peoples who lived there, including in the Boumba Bek and Nki National Parks in Cameroon.

Another chilling example comes from Botswana, where the San people now face instant death at the hands of sharp shooters for ‘poaching‘ on lands they have hunted on for millennia. These hunting grounds now lie within the Central Kalahari game park, where Gem Diamonds’ Ghagoo Diamond Mine, opened in 2014, spans the entire ancestral territories of the Gana and Gwi Bushmen.

Similar patterns, in which Indigenous Peoples are dispossessed and national authorities then fail to protect the lands they have taken, are observable all over Africa and Asia, says Tauli-Corpuz.

“We can agree with the goals of conservation, but if these protected areas are then being overrun by mining companies, what is the point of conservation?” she asks.

In this context, Motion 26 represents a stride in the right direction. Containing recognition of the leading role indigenous communities have to play in conservation efforts and “the need for respect of Indigenous Peoples’ right to free, prior, and informed consent”, it is a move towards decolonizing the norms of global conservation.

“Motion 26 is historic”, says Nigel Crawhall, Director of the Secretariat for the Indigenous Peoples of Africa Coordinating Committee and a proponent of Motion 26. “It is the broadest ever coalition on protected areas and conserved landscapes and represents a new solidarity between professional conservationists and traditional owners and custodians. The Durban World Parks Congress called for a rights-based approach to conservation and inclusion of Indigenous Peoples in decision-making. Motion 26 puts that into action beyond the limits of national parks.”

A number of other motions approved at the Congress also give cause for optimism that the ideas and attitudes driving conservation are changing.

For example, another Motion passed during the Congress (Motion 48) calls on government, the private sector and financial institutions to protect primary forests and to “meaningfully engage and support Indigenous Peoples and local communities in their efforts to conserve primary forests, including intact forest landscapes.”

IUCN members also voted to create a new membership category for Indigenous Peoples organizations at the Congress. This is the first time in the IUCN’s history that a new membership category has been created.

The move will give Indigenous Peoples an official presence in the IUCN’s decision-making structure, enabling them to help determine the future direction of conservation policy on issues such as indigenous rights and sacred lands.

Though Motion 26 is not legally binding on governments or businesses, supporters say that it can be an effective tool for indigenous and local community activists struggling to protect sacred natural sites.

“By adopting this measure the IUCN has blown wind into the sails of indigenous campaigns for territorial defense and offered civil society a tool to help strengthen national level protected area norms to include sacred natural sites”, says Amazon Watch’s Andrew Miller.

Caleen Sisk, Chief of the Winnemem Wintu of northern California and one of the custodians present in Hawai’i, says “The challenge now is to identify a mechanism that will successfully make these sacred places permanent No-Go Areas – where indigenous knowledge and rights are respected.”

Chief Caleen Sisk of the Winnemem Wintu tribe, USA, and Chief Appolinaire Ousso-Lio, Benin, interviewed at the World Parks Congress

“We still need enforceable laws to save our sacred sites,” adds Sisk, stressing that the long-term success of Motion 26 relies on its implementation.

Winning concrete protections for sacred sites at the national level is a task Indigenous Peoples and their allies will have to negotiate in their own contexts. But growing recognition from, and roles within, influential international conservation groups like IUCN can only help.

Patricia Gualinga of the Kichwa indigenous community of Sarayaku, Ecuador, says that the success of Motion 26 will inspire her community to secure the protections they seek for their forest home.

“For us, the Indigenous Peoples who promote Kawsak Sacha (the Living Forest), we are hopeful following the IUCN adoption of Motion 26. This will help us continue advancing and fighting to see it implemented from our perspective as territorial guardians.”

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.