The III Continental Summit of Indigenous Communication in Bolivia promised to be the most important event for indigenous media in 2016. Unfortunately, the gathering was marred by disagreement. The government set out to define the agenda; the attending indigenous communicators set out to resist it.

The summit took place from Nov. 15 to 19, 2016, in Tiquipaya, Bolivia and included a large state presence. The indigenous communicators quickly felt displaced by the omnipresent state. This led to the creation of an independent board that made its own declaration parallel to that of the official (and government party) summit.

The Third Summit of Indigenous Communication in Tiquipaya

A people without a voice are a dead people: communication is essential in order to create an awareness of the people and to legitimize their struggles. In this sense, the people’s resistance through their autonomy contains an important communication component for saving memory and defining organizational strategies at a local and international level.

It is in this spirit that the idea of continental summits for indigenous communication arose in 2009 during the Fourth Continental Summit of the Peoples of Abya Yala in Puno, Peru. It was there that communication was raised as an essential issue in the construction of the autonomy that a proper summit needed. The aim was to bring about areas of resistance through communication, turn back the invisibility of indigenous peoples in mainstream media and amplify the relevance of indigenous experiences.

The continental conferences of indigenous communication are born as autonomous spaces that meet weeks before the People’s Summit in order to present their agenda for general approval.

The first summit of communication was held in November 2010 in the autonomous indigenous reservation of La María Piendamó, Cauca, Colombia. A second summit was organized in October 2013 in Santa Maria Tlahuitoltepec Mixe in Oaxaca, Mexico, where Bolivia’s candidacy was approved for the third summit of indigenous communication.

The third summit was held in November 2016 in Tiquipaya, near Cochabamba, Bolivia. The meeting brought together about 1,500 people in the buildings of the Universidad del Valle under eight core topics: communication for decolonization; legislation and legal framework; training; advocacy strategies; gender equality; sovereignty and technological challenge.

Delegations arrived from Guatemala all the way to Argentina, with a strong Andean presence from Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. The Bolivian peoples were the most represented—for example, the delegation from Beni had over 70 people.

Many chewed coca leaves, and all discussion areas had several cameras. Bolivian police, with Bolivian and Abya Yala flags on their shoulder, were in several areas of logistics: at the entrance of the auditoriums they made note of the participation, provided information, and distributed food to participants. The formal atmosphere seemed at times more like a United Nations meeting than a community conference.

The cement buildings of the university campus offered ample meeting spaces, however this took away from the community aspect. In the coliseum, one could attend long speeches by the Ministers of Foreign Affairs, of Decolonization and of Communication, where they talked about the “good life” and the indigenous concept of sumak kawsay. Thematic tables were located in different buildings and floors, discussing various topics from the right to have TV networks to the role of indigenous architecture in redesigning public spaces.

The table on training discussed three main proposals: an itinerant school for communicators, a virtual platform, and possible forms of diploma and degree qualification so communicators could practice their profession in various media outlets. Other tables considered the importance of circulating experiences between different processes of preliminary, free and informed consultation in order to consolidate strategies of resistance.

There were complaints, mainly due to logistics failures (lack of food) and delays, such as the final plenary session that took place a day late when many participants had already left. In terms of the legal framework, they commented that attention needs to be paid to the source of funding and the conditions that go with it: “The one who finances is the one who imposes conditions”. For some, this was the pivotal point that sealed the disagreement.

A co-opted summit

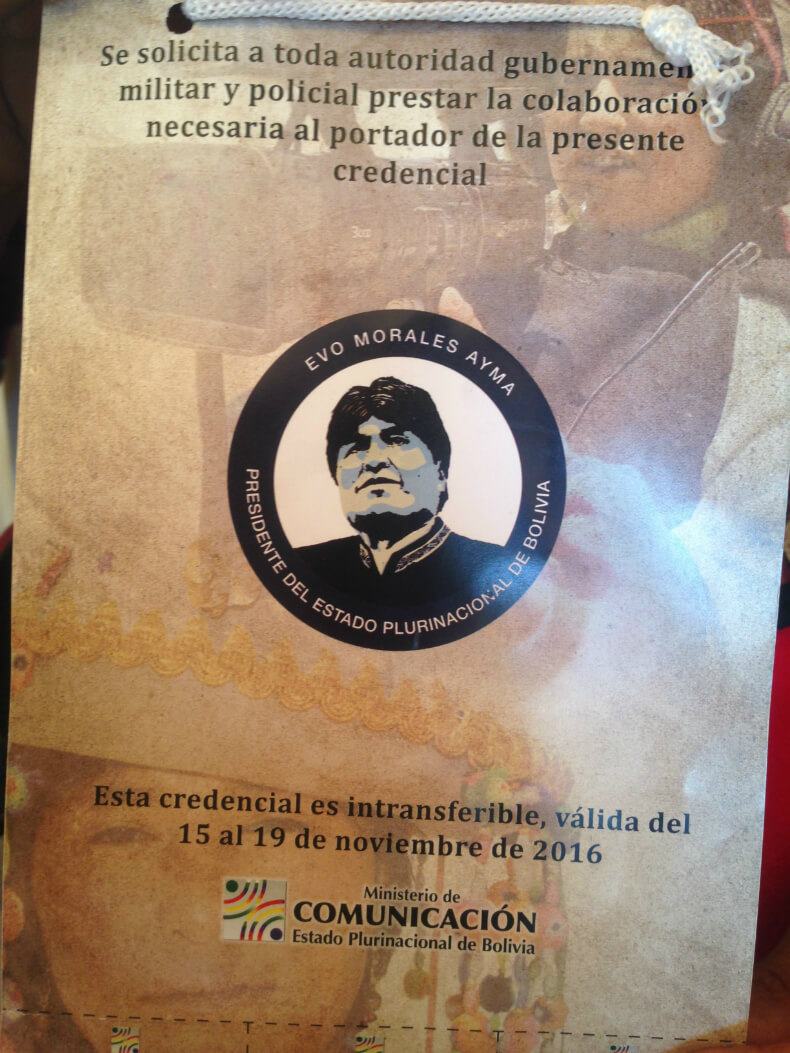

The summit received support from the government of Evo Morales, and it was impossible not to notice. The face of President Evo was in all event materials —from the informative brochures to the credentials that each participant had hanging on their chest. Evo opened the summit, expressing a pro-government and almost electoral tone by closing his speech with a “Viva Bolivia! Viva Evo!”, and he earned the nickname Ego.

Young communicators like Angel Apaza Cotrado of the Organization of Aymaras Women (UMA) who traveled two days from Puno to get there, expressed their disappointment: “Evo’s opening felt more like a political campaign and some tables focused on what happens in Bolivia and not on regional issues”.

Angel Apaza Cotrado (left) and Manuela Picq

Several indigenous communicators denounced excessive government intervention and felt that their community space was invaded by the state beyond the worship of the President: they claimed that areas were taken by state representatives, that the Ministry of Communication not only supported the event but that he also controlled the agenda, and that procedures not at all community oriented did not allow any indigenous communicator influence.

Representatives of Ecuador opposed the idea of Ecuador’s Ambassador in Bolivia speaking in the plenary session, suggesting that a government that criminalizes indigenous peoples can not come to speak on their behalf at an indigenous summit. The Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE), an organization that now celebrates 30 years of existence, made its position clear in that regard: “it is the people’s summit, not the government’s”.

The opposition created an “autonomous table” off campus, under tents in the parking lot, without electricity, away from the microphones. Communicators from the whole region regrouped there, disaffected with a “hijacked” summit: communicators from Mexico to Argentina, from the Wayuu and Aymara peoples, from members of organizations such as the Regional Council of Cauca in Colombia (CRIC), the Confederation of Nationalities Kichwas of Ecuador (ECUARUNARI), the Network of Indigenous Communicators of Peru (REDCIP), SERVINDI, and the Bartolina Sisa National Confederation of Campesino, Indigenous and Native Women of Bolivia.

Even the renowned Cuban Jose Ignacio Lopez Vigil, special guest of the ruling party, stated that “there was a major mistake” on the part of the Ministry of Communication of Bolivia in its treating the summit as a government space. “The whole facade was made up of Bolivian authorities” he added.

The Bolivia failures were predictable. The tension between the government authorities and the resisting communicators reached its peak in Bolivia but it already had precedents. At the Summit of Oaxaca, the organizers invited President Peña Nieto for having supported the organization of the conference and communicators of organizations such as CRIC left the meeting in protest. During the third summit, in addition to the independent board and participants returning early, communicators from the Bolivian department of Beni protested the government authorities during the final closing.

The two summits of Bolivia: the official declaration and the actual space

As Lopez Vigil said, the Tiquipaya Summit was marked by lights and shadows. New horizons, such as the creation of an Itinerant School for indigenous communicators, were generated. In the legal field, they agreed to create a legal commission to defend the rights of media at the community level. In addition, they set out to create an Organization of Indigenous Communicators of Abya Yala, similar to other news organizations in the world, or a continental connection.

But there were actually two summits: the party-line one taken over by the government of Evo Morales and the autonomous space in resistance.

The official statement of the summit failed to hide state interference, stating in point 14 “Bolivia is a pioneer in indigenous communication”. It maintained a political vacuum of conventional institutions by promoting gender equality and dispatriarchalization by “promoting the active participation of women in communication.” And, Guatemala was chosen to host the next summit.

What was suggested at the autonomous table is that the problem went beyond Bolivia, a complaint placed before one government and another government, and yet another, and that the challenge was to build a system truly independent from state influence.

The independent board became a space of its own which showed solidarity with indigenous and peasant movements in defense of their territories and water, and in resistance against extractive industries without prior consultation, from Standing Rock in the United States to Jujuy in Argentina. The independent board first positioned itself as its own space with a declaration clarifying their differences with the pro-government summit. The space then adopted a statement of its own; and it established a road map for the coming years.

A communication conference will be held in August, 2017 in Cauca, Colombia, during the week for the Liberation of Mother Earth, prior to the Sixth People’s Summit. Delegations from Ecuador offered to organize a preparatory communication event in 2018 and the delegation from Peru offered an international event in 2019 in Cusco. All with the goal of re-articulating indigenous communication with the struggles in defense of water and territory in the Abya Yala.

It is ironic that a plurinational state with an indigenous president might seek to invade the autonomous areas of self-determination of the Abya Yala people. The conference of indigenous communication was born out of the diversity of peoples precisely in order to resist the homogenizing control of the states.

Now that the meeting of indigenous communication has resulted in a failure full of disagreement and that two paths are being created, let’s hope that these two distinct spaces, one of more institutional tone and the other categorically activist, will enter into constructive forms of competition in order to generate more diversity of experiences and training to bolster indigenous communication, each in their own way.

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.