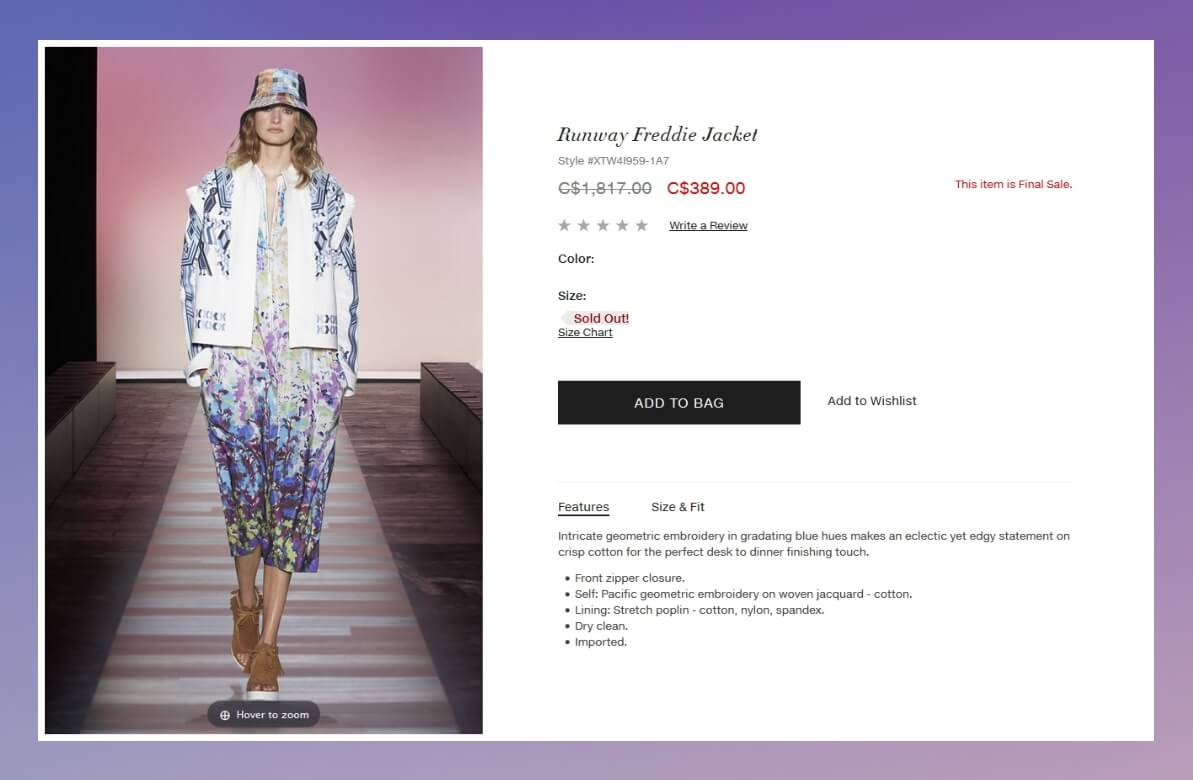

With $1400, you could buy an iMac or a trip to Europe. You could also buy a designer jacket made by the fashion label BCBG Max Azria, a white one with intricate blue geometric patterns running over the sleeves and down the body. It is expensive, it is pretty, and it is inspired by designs stolen from indigenous Maya communities.

Such appropriation is at the crux of work that is being carried out by Angelina Aspuac and her colleagues at the Association of Maya Weavers in Guatemala. During a lecture that was delivered at Amherst College this past spring, Aspuac, a Maya lawyer and activist, and former president of Asociación Femenina para el Desarrollo de Sacatepequéz (AFEDES – Women’s Association for the Development of Sacatepequéz), talked about the harms of intellectual theft. The BCBG jacket is an example of the parallels that exist between this phenomenon and traditional forms of extractivism: corporations extract knowledge from indigenous communities so that they can export them as commodities in the global market, all without compensating or recognizing those communities in any way.

Intellectual theft is just as harmful and violent to Maya ways of life as territorial dispossession.

Angelina Aspuac (right) accompanies a weaving workshop in Chichicastenango. Every community has its own design traditions. Maya weavers regularly meet to share knowledge, analyze designs, and systematize the traditional güipiles within and across communities.

Aspuac ties dispossession of Maya land (physical property) to the theft of Maya textiles and designs (intellectual property).

Maya ideology values the practice of utz’ k’aslemal, or “living well,” in which vida – life – is inherently connected to the land, the day, the night, the air, the earth. The Maya people need their land to survive, for it provides them with food. But clothing, too, is necessary for survival. In fact, Aspuac describes the stealing of land and the stealing of textiles and designs as equally dispossessive. She fears that as fewer and fewer Maya wear indigenous clothing and weave using indigenous techniques, their way of life will become seen as something of the past – something shown in museums but not viewed as a dynamic part of the modern world. But she points out that, ironically, as Maya stop conducting their traditional forms of cultural practice, non-indigenous people around the world are increasingly using Maya culture for their own benefit.

The designer jacket described earlier is just one of the many cases of theft of indigenous knowledge by the fashion industry; Designs are being stolen, weaving techniques are being erased and machines are replacing the weavers. Put another way, the textile tradition is being industrialized, which erases the knowledge and practice of weaving as a crucial part of Maya lifeways.

The process is as important as the product, but in this act of cultural dispossession the former is being ignored completely. What’s more, due to effective advertising and easy accessibility, people buy Maya-inspired clothing from multinational clothing corporations without ever being exposed to real Maya textiles or understanding Maya philosophy.

Weaving güipiles is a slow process that engages inter-general knowledge, community memory, and Maya mathematics. It takes months of work to weave one güipile and they are passed on across generations.

According to Aspuac, the pattern on BCBG’s jacket is an almost exact replica of a traditional Maya pattern, from which the Maya could read and tell a folk story. Without knowing the meaning behind this story, or caring to learn, BCBG cut and flipped the pattern for use on jackets, shoes, bags, and swimsuits.

The company sells the altered designs at high prices, assigning new meanings and values to the appropriated textiles.

Another example can be found on BCBG’s designer shoes. The Maya use specific textile patterns that are only used on shoes worn by traditional authorities. Now, the designs are used upside down on shoes worn by random non-indigenous people around the world.

“Textiles elaborated by Indigenous Peoples Are Heritage of the Peoples”

The definition of extractivism lies in large corporations accumulating profit through the large-scale production of extracted resources. The exploitation of textiles and intellectual property for profit by companies like BCBG and its commodification and slow erasure of Maya identity certainly lend credence to our calling the extraction of indigenous knowledge a form of extractivism.

When companies steal Maya knowledge without compensating or even citing their origin, they participate in what Rob Nixon calls “slow violence.” Nixon uses the term to refer to slow, long-term processes of climate change, but the principle can be used here to depict the slow-moving yet equally destructive appropriation of Maya territory.

If the company were to rip güipiles (a traditional blouse) off the bodies of the people wearing them and sell those stolen goods in stores, they would be committing an act of violence that Nixon labels “spectacular,” overtly and physically harmful and obvious for all to see (a spectacle). However, BCBG’s acts of “slow violence,” which gradually devalues the Maya as a source of worthwhile knowledge and production, are far more difficult to recognize, and far more difficult to condemn.

Challenging the violent dispossession of the fashion industry is the focal point of the Association of Maya Weavers in Guatemala. In most cases of anti-extractivism and indigenous-led demonstrations for self-determination, the connection between the land and the colonizer practices of big corporations is direct: people defend the land on which they have lived for generations from being exploited by a greedy outside force for its own benefit. The case of the Maya weavers, however, shows us how a society’s culture and intellectual production are valuable resources, intrinsically tied to the land. The protection of culture is just as essential to self-determination as is the protection of territory.

In an article from 2012, Jeff Corntassel and Cheryl Bryce discuss the link between self-determination and the preservation of cultural heritage. They highlight decolonization in local contexts; for example, in discussing the Lekwungen indigenous community, Corntassel and Bryce write that “by resisting colonial authority and demarcating their homelands via place-naming and traditional management practices, [their] everyday acts of resurgence have promoted the regeneration of sustainable food systems in communities and are transmitting these teachings and values to future generations” (160). The general principles in the passage are the same as those found in the efforts of the Maya textile weavers: the Maya’s (rightful) claiming of their traditional textile designs and methods of production demonstrate “an everyday practice of [indigenous] resurgence and decolonization” (153). Corntassel and Bryce are concerned with the idea of revitalization and restoration because it centers around the reclamation of an indigenous cultural practice. Fortunately, in the case of Maya textiles, the tradition is not in a state of needing to be revived from the past. It is currently alive, but endangered; Aspuac and other women are fighting to make sure that they do not lose it permanently.

The Council of the National Movement of Weavers (Ruchajixik ri qana’ojb’äl) holds monthly meetings to exchange knowledge and articulate the politics of collective intellectual property rights. Hundreds of collectives from across Guatemala participate in the defense of textile heritage.

The fight for proper recognition of Maya intellectual work is a fight for a sustainable way of life – sustainable in that it connects the Maya to their land, and sustainable in that it is tied to the continuation of their culture and heritage. In resisting the theft of their intellectual property, Maya weavers are accounting for the presence of three generations: their own presence; the presence of their ancestors, all the women who came before them and who passed the knowledge and traditions down; and the presence of future generations, to whom the current weavers will pass on their knowledge.

The stealing and appropriation of Maya textiles and designs contributes to the slow erasure of indigenous peoples from the cultural map of the world. The concurrent dispossession of indigenous land only furthers the issue at hand, for it contributes to the slow erasure of indigenous peoples from the geographic map of the world. By spreading awareness of these dual forms of dispossession, Aspuac and other weaver-activists affirm their power as a people who contest historical forms of exploitation, who refuse to be wiped out.

Aspuac describes the very tools that corporations use to steal land and designs from the Mayas – convoluted legal processes – as able to be used by the Maya against those same corporations, to ensure that the stealing stops. As we continue to think of ways to combat extractivist processes of large multinational corporations, however, we are left questioning the productivity of fighting capitalist western corporations with the very tools created by capitalist western states, such as legal defense. We think back to Corntassel and Bryce, who emphasize that the search for self-sovereignty should neither be nor have to be conducted within this western framework by describing “indigenous self-determination [as] something that is asserted and acted upon, not negotiated or offered freely by the state.”

On April 19 2017, the Movement of Maya Weavers presented a project of law to protect collective intellectual property rights (Law 5247) to the Commission on Indigenous peoples at the Congress of Guatemala.

We question, like Donna Haraway asks us to in her 2014 talk on the “Cthulucene,” whether we need to imagine new ways of thinking to appreciate the issue at hand. To imagine new forms of governance, perhaps, ones that condemn the stealing of indigenous land and culture without resorting to terms like “legal rights,” and that value the Maya way of life not because it is “property,” but simply because it is their vida.

Sunna Juhn is a recent graduate of Amherst College, where she majored in American Studies and French.

Emily Ratté is a recent graduate of Amherst College, where she majored in Sociology and Asian Languages and Civilizations.

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.