“He will try to buy the land from you, but do not sell it; keep it for an inheritance to your children.”

~ Asiniiwab (Little Rock)

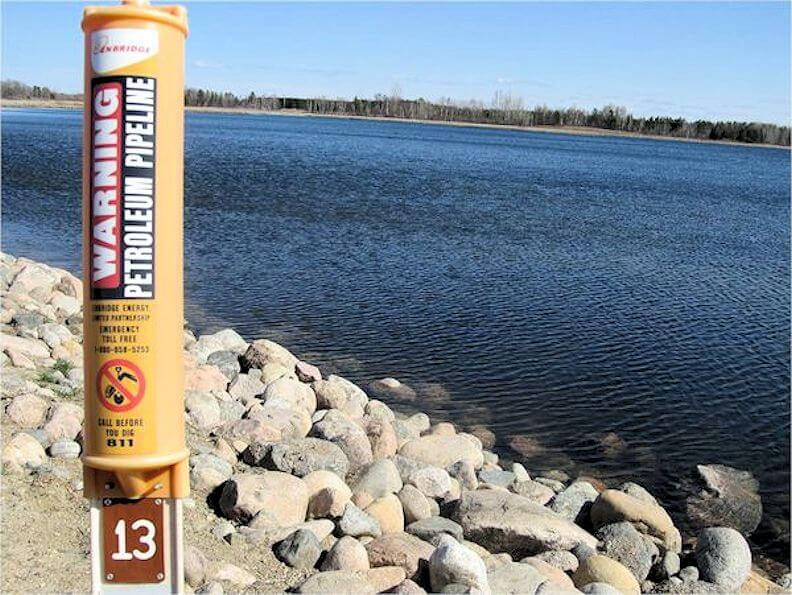

On February 28, 2013, a .45 acre of Red Lake ceded land became the focus of Anishinaabe land defenders and pipeline activists. Led by Red Lake member Marty Cobenais, the Nizhawendaamin Inaakiminaan (We Love Our Land) group established an encampment over the Enbridge pipelines at Leonard, Minnesota. Cobenais said at the time, “We plan to camp on this land until the pipelines cease to pump oil through them.”

Although the encampment wasn’t sanctioned by the Red Lake Tribal Council, a Red Lake District Representative visited the site and informed Cobenais that the pipelines were illegally on Red Lake land and the council wanted them removed.

A sacred fire was lit and a medicine pole was erected. The camp continued through the late winter into the early fall. It was supported by environmentalist and activist groups including the Indigenous Environmental Network and MN350.

Through its educational tours at the camp, Nizhawendaamin Inaakiminaan successfully created a broad awareness of the destructive hazards associated with Enbridge and its pipelines. However, the effort to shut down the pipelines was unsuccessful. With the dispersal of the camp in the fall, there were hopes that Darrell Seki, the newly elected chairman of the Red Lake Band, would press forward by charging Enbridge with trespass and force a removal of the pipelines.

The area where the Enbridge encampment was located has deep roots in the history of Miskwaagamiiwi-zaaga`igan (Red Lake). Before the treaty making period, the area was part of the vast domain of the Red Lake Ojibwe-Anishinaabeg that extended west into North Dakota and into parts of Manitoba and Ontario. Numerous small hunting and trapping communities, largely composed of clans, inhabited the area between Red Lake and North Dakota.

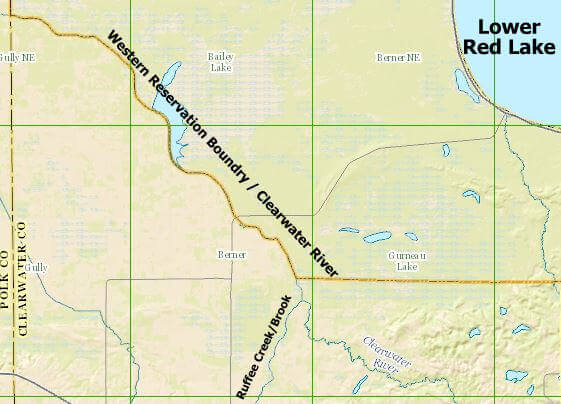

Lakes provided locations for settlements and rivers served as routes to the Red River fur trade. The Gaa-waagamig-zaaga`igan (Clearwater River) flowed west and emptied into Miskwaagamiiwi-ziibi (Red Lake River) which flowed westward to drain into Miskwaaziibi (Red River); Miskwaaziibi flowed north into Manitoba and drained into Lake Winnipeg.

Niiyo-Gaade-ziibiins flowed west out of Niiyo-gaade-zaaga’igan and turned north to drain into Gaa-waagamig-zaaga’igan approximately 15 miles upstream. The creek and the lake were named after a Red Lake Ojibwe man who lived there – Niiyo-Gaade, or Four Legged.

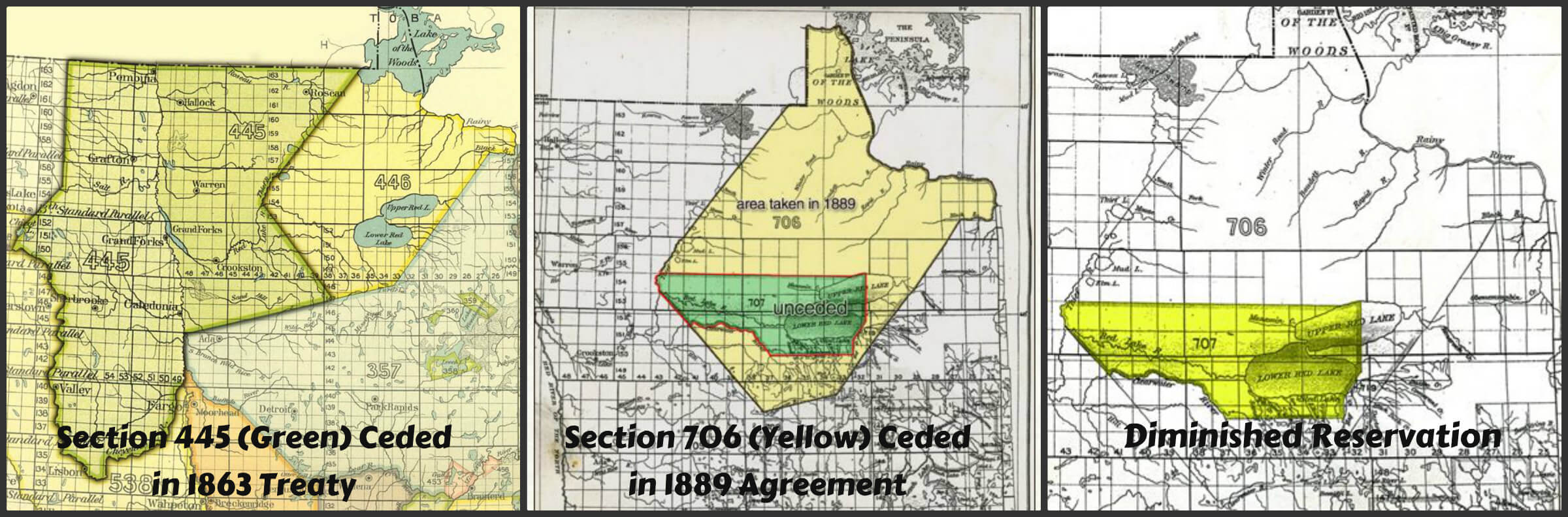

Under the Old Crossing Treaty in 1863, over 11,000,000 acres were ceded in North Dakota and western Minnesota by the Red Lake and Pembina Bands. After the treaty, Red Lake was left with a land base of 3,260,000 acres. In the 1889 Agreement, another 2,905,000 acres were ceded including Niiyo-gaade-zaaga’igan.

However, before the 1889 Agreement was signed, the Red Lake unceded lands were trespassed upon by timber companies who roamed through the region to clear-cut the virgin forestland. Homesteaders followed in their wake. As early as 1886, settlers began to move into the area under the guise of the Homestead Act of 1882, although the Act was not legally binding on land that had yet to be ceded.

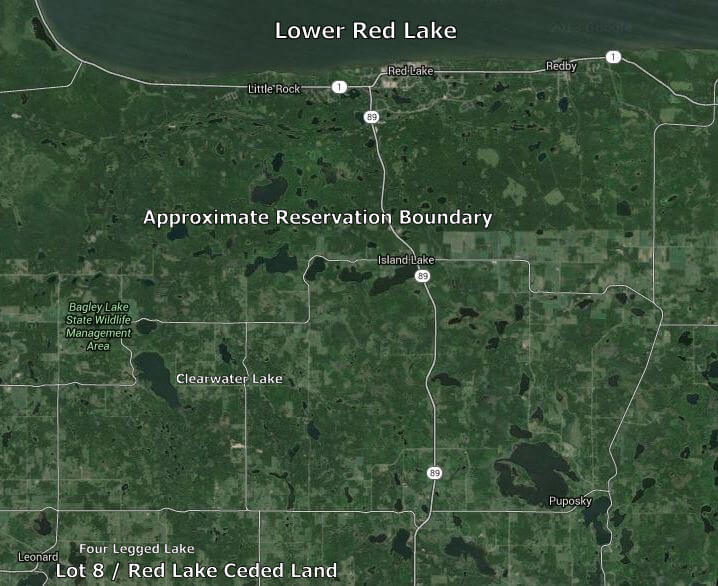

In 1902, the area disassociated itself from its Ojibwe roots, and, under the tenets of Euro-American colonialization, the area became Clearwater County. Niiyo-Gaade-zaaga’igan was renamed Four Legged Lake and its creek became Ruffee Creek after Charles A. Ruffee, who wrote the “Report of the Condition of the Chippewa.” Today, the Clearwater River (formerly Gaa-waagamig-zaaga-igan) marks the western border of the Red Lake Diminished Reservation.

In 1945, Oscar Chapman, Assistant Secretary of Interior, signed an Order of Restoration that restored unsold ceded lands of the Agreements of 1889 and 1904 to the Red Lake Band. According to the Order:

“Whereas, according to the records of the Commissioner of the General Land Office there remain of such ceded lands 157,000 acres, more or less, which have been opened to settlement and sale and which now are or hereafter may be classified as undisposed of, for which the Indians have not been paid, and which are of little or no value for the original purpose of settlement but which will prove of value to said Indians of the Red Lake Reservation if restored to tribal ownership…”

The size of the tracts varied from over 600 acres to as little as .30 acres. The small tracts had little use in terms of property; many were located on the edges of farm fields or within woodlands. In 1999, the tracts were recorded in the Federal Register including Lot 8, a .45 acre tract, located at Four Legged Lake in Clearwater County.

However, Lot 8 wasn’t a useless tract of land located in the middle of a swamp or field. Its value was disproportionate to its size. Each day, millions of dollars flowed through the four pipelines buried three feet under its surface.

The history of trespassing that began with the timber companies and homesteaders continued in 1949 when the Lakehead Pipe Line Company built a pipeline that crossed a tract of unceded Red Lake land, Lot 8, at Four Legged Lake. Additional pipelines followed in 1954, 1963, and 1973. In 1968, Enbridge bought Lakehead and continued the trespass by replacing the old pipelines with the Alberta Clipper and Southern Lights pipelines.

In addition to trespass, there was a dark side to the pipelines. During the Enbridge encampment, Tito Ybarra, a protester from Red Lake, said: “It’s not a question of if these pipes will leak—it’s just when, and where. The oil and chemicals they use to harvest and produce this oil are very, very toxic. It gets into the groundwater, which gets into the rivers and streams, and it causes cancer. It’s been poisoning communities up in Canada.”

A Kalamazoo-type spillage at Lot 8 presents a grave danger to Red Lake lands. A spill at West Four Legged Lake, where Lot 8 is located, would enter Ruffee Creek (also called Ruffy Brook), flow north for approximately 15 miles, and join the Clearwater River. From where the two intersect, it is about a mile to the Red Lake border. Although such a spillage wouldn’t reach Lower Red Lake, it would affect a critical fish and wildlife habitat on the western border.

On December 21, 2015, the Red Lake Tribal Council issued a release to tribal members:

Enbridge and the Band have agreed to exchange land, and Enbridge will pay 18.5 million for the trespass at the Four Legged Lake property. Within a month, Enbridge will place 18.5 million in an interest building escrow account. In exchange, the Band will designate one or more parcels of land within the 1863 treaty area/1889 agreement for Enbridge to purchase on behalf of the Band and will begin the fee to trust land exchange. Red Lake’s constitution and federal regulations require that the land coming into trust must be of equal or more value than the land coming out of trust. Once the land exchange is complete, the Band will take possession of the total value in the escrow account including any interest.

The Council will vote to either accept or deny the agreement during the December 22, 2015 Special Council Meeting.

At the special meeting on December 22, the Council released a 6-page document to tribal members – “A History of the Enbridge Pipeline Trespass and Negotiations.”

The Pipelines and the Trespass

The BIA issued a Notice of Trespass, which the Band requested that the BIA not act on because negotiations were underway, and

Enbridge installed the two new pipelines (Alberta Clipper and Southern Lights) on a slightly different route so that they would not pass across the Band’s Lot 8 Lands.

The Negotiations

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Alternatives / Litigation:

If Red Lake were to litigate the trespass, it would enforce the existing Notice of Trespass in Tribal Court. It would have two options:

The Settlement / The Land Exchange:

According to Red Lake’s attorneys handling this matter, the settlement for $18.5 million is the best agreement that any tribe, anywhere, has received from a pipeline or energy company, and the land exchange and land acquisition provide tremendous benefit to Red Lake. The Tribe will choose the land it gets in exchange for the Four-Legged Lake land.

Contrary to popular belief, Lot 8 is not located on the Reservation, but approximately 16 miles from the Reservation border.

A massive oil spill could, in fact, affect fish and wildlife habitats along the Reservation border. Ruffee Creek drains into the Clearwater River approximately 1 mile from the western border of the Reservation.

There are several inconsistencies in the December 21 Letter and the December 22 Enbridge Agreement.

The December 21 Letter states: “Enbridge and the Band have agreed to exchange land, and Enbridge will pay 18.5 million for the trespass at the Four Legged Lake property.” The last sentence reads: “The Council will vote to either accept or deny the agreement during the December 22, 2015 Special Council Meeting.” According to sources, the council accepted the agreement on Friday, December 18. Why the presumption that the council would “accept or deny” the agreement on the 22nd when the decision had already been made?

One glaring inconsistency in the Enbridge Agreement can be found under Pipelines/Trespass that states: “Enbridge installed the two new pipelines (Alberta Clipper and Southern Lights) on a slightly different route so that they would not pass across the Band’s Lot 8 Lands.”

If the pipelines were moved off of Lot 8 in 2009, then how does one explain that the encampment was right on top of the pipelines at Lot 8 in 2013? Then there is the matter of the map. The map clearly shows pipelines crossing Lot 8. If the pipelines had been moved “on a slightly different route,” then there wouldn’t be a need for an $18.5 million trespass payment and land exchange.

Despite these glaring inconsistencies, the December 22 Agreement makes it clear that the Band is giving up the trust status of Lot 8: “Red Lake gets to choose the land it gets in exchange for the Four Legged Lake land.” This means that the Band will no longer retain possession of Lot 8 and Enbridge’s pipeline will remain in place. Of course, there is the question of who will own Lot 8 – Enbridge, the township, the state? Regardless, Enbridge will continue to pump its tar sands through the pipeline.

In giving up Lot 8, the council absolves itself of any responsibility of an Enbridge spill, proclaiming outright that “Red Lake avoids the possibility of having to deal with an environmental disaster and contamination at Four Legged Lake in the future.”

Like Pontius Pilate, the tribal council is attempting to wash its hands of any environmental guilt and shift the blame elsewhere.

For Anishinaabe activists, the selling of Lot 8 is the loss of a strategic point in the opposition to pipelines. The Band had the perfect opportunity to demand the dismantlement of the pipelines on Red Lake land or in the very least force Enbridge to reroute their pipeline at the company’s expense. Instead of going down this path the tribal council acquiesced, effectively sanctioning the history of trespass at Four Legged Lake. In so doing, it allowed Enbridge to continue counting daily profits from its poisonous makade-ginebig (black snake).

Beyond the obvious concerns of Native environmentalists, there is a sense of frustration and betrayal among many Red Lakers. Tribal members weren’t allowed to accept or deny the Enbridge deal through a referendum vote; rather, the decision was made behind closed doors by a council that was elected to protect the homeland.

The decision has also led to concerns and criticism of the tribal council. Children have asked if the pipeline will destroy the lake. Some members have questioned how much money was taken under the table. Others have called for a referendum vote or a recall election.

The essence of the anger was best described by one tribal member: “The integrity of our nation was sold.”

That sense of integrity emanates from the Red Lake ogimaag (leaders) who, in 1863, 1889, and 1902, maintained the homeland despite tremendous pressure from the government to open the land up to extractive companies and settlers. But the danger of losing the homeland is always present. Once a door is opened not only does it never close, it slowly opens wider.

The integrity that flows in the blood of Red Lakers for their homeland is found in the words by Asiniiwab (Little Rock), an ogimaa who was present at the 1863 Old Crossing treaty negotiations:

“My friend, it is only twenty boxes of money you want to give me for that road and river; and how long before you cease from using it? Ever since I can remember, and perhaps since the world was made, the river has given me sustenance…you say that the land is not of much value to us. It is of great value to us. By your use of it you have made a great deal of money…the river furnished me a living. I drank its water. The beasts that engendered on its shore gave me the clothing I wore. You say it was of no value to us. It is there where we used to get everything we had.”

©2015, All Rights Reserved, Robert DesJarlait

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.