This pamphlet is part of an upcoming campaign on the ongoing effort of the Canadian government to terminate First Nations sovereignty and identity. Because of the surprise announcement of an agreement with the Algonquins of Ontario, we are making a download of this pamphlet available early. If your community is at a treaty negotiating table, you need to read and understand this short pamphlet. Print it out and pass it around your community!

The recent announcement by the Trudeau government that Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada is opening 20 “exploratory tables” to possibly develop new terms for the land claims and self-government processes must address the current core federal mandates listed below. We reject the euphemistic changes to the policy that replaced “extinguishment” to “modification” to “certainty” to “recognition” without ever changing the termination plan.

THE POLICY

What is the Comprehensive Land Claims policy?

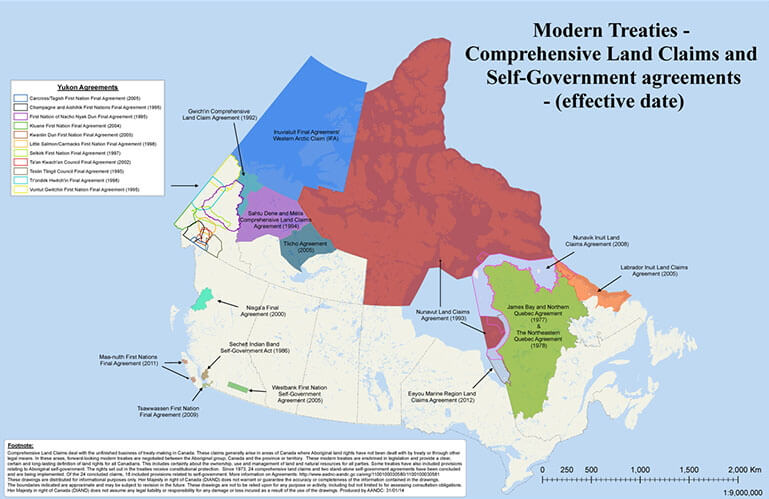

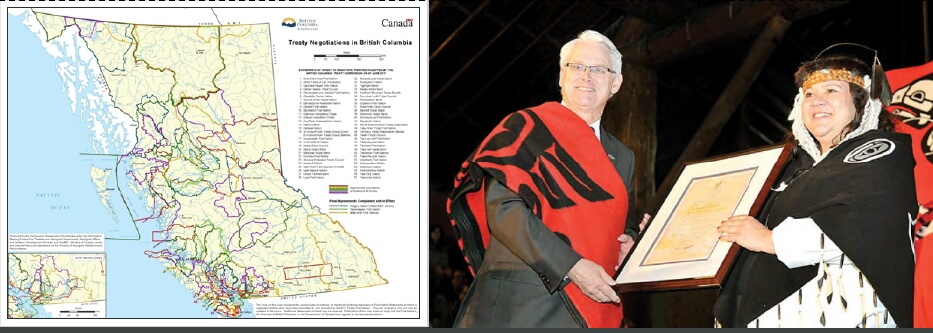

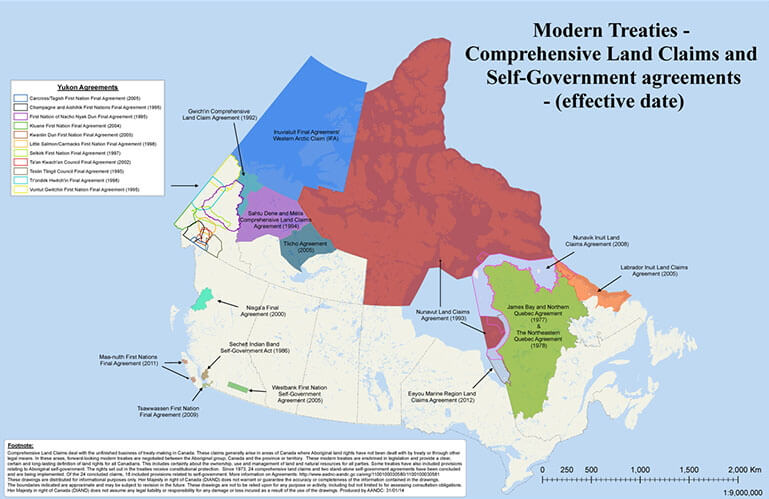

The Comprehensive Land Claims policy is a federal policy that was introduced in 1973 as a political process to resolve all outstanding land grievances on all Indigenous land in Canada not subject to historic land treaties. It includes Inuit and First Nations land, but not Métis land. Though there are a number of land settlement processes in Canada, such as the British Columbia Treaty Process and the land claims tables in Ontario, Quebec and the Atlantic, these regional processes are governed under the terms of the federal Comprehensive Land Claims policy.

What negotiators do not make clear from the start is that the policy involves a number of absolutely non-negotiable federal core mandates, which are essential for community members to know.

- Extinguishment: You must consent to the extinguishment of your Aboriginal title. The lawyers and negotiators call this the “modification” of rights or “non-assertion.” These are legal weasel words: none of the legal protection for Aboriginal title lands will apply on modern treaty lands.

- Private Property: You must consent to the elimination of Indian Reserves by accepting all settlement lands as fee simple (private property). Fee simple lands can be bought, sold, and lost to outsiders. Unlike Indian Reserves, fee simple lands are not governed under federal jurisdiction or under the Indian Act. But this does not make them sovereign Indian land. Rather, fee simple lands fall under provincial jurisdiction and must be governed to comply with provincial land regulation, as well as applicable federal regulation. This is the scenario critics call the transformation of reserves into “ethnic municipalities.”

- Land Selection, aka Surrender: The government has a cash/land formula that is not public, but can be determined by averaging out every Agreement in Principle and Final Agreement that has been signed, roughly $25,600 per person and 9 hectares (23 acres) per person. In the British Columbia Treaty Process, for example, negotiating groups cede an average of 95 percent of their traditional lands.

- Third Party Interests: You must respect existing Private Lands/Third Party interests, This means you must consent to the alienation of Aboriginal Title territory and give up all right to compensation for past infringements.

- Incorporation: Your band becomes the legal entity of a corporation, with powers and privileges defined in the Final Agreement. You are no longer a First Nation, but a business entity under the law.

- Taxation: You must give up on-reserve tax exemptions and begin paying income taxes within an established period following approval of the Final Agreement. When you have to start charging tax on sales, and also paying taxes for your employees, it will entirely or largely remove your competitive advantage.

- Governance: You will have no jurisdiction in the following matters: powers related to Canadian sovereignty, defence, and external relations; management and regulation of the national economy; maintenance of national law and order and substantive criminal law; protection of the health and safety of Canadians; federal undertakings and other powers. In other words, you will have no control over economic trade, no say in federal undertakings like highways or hydro dams that take place on your territory, and no autonomy in negotiations with other nation states. Your law making authority, which negotiators will exaggerate, will be subject to federal or provincial / laws and oversight in the event of jurisdictional conflict. Any decision you want to make that overlaps with provincial jurisdiction will require participation and agreement by the province.

- The Inherent Right policy: You will assimilate your governance system into the framework of the Canadian Constitution and be expected to “harmonize” your laws in a manner “which is indispensable to the proper functioning of the federation.” In contrast to having sovereign authority or jurisdiction over your lands, based on exercising Indigenous law, you will be expected to join federation, just like other Canadians, with no specific Indigenous rights.

- Funding Framework: You will eventually lose federal support for programs and services as the province / territory takes over responsibilities for programs offered to all Canadians and you are expected to make up for budget shortfalls through local, own-source-revenues. You will have moderate taxation powers over local matters, such as property tax of your members on your treaty entitlement lands, but these are also concurrent with provincial / territorial jurisdiction.

There are several other core federal mandates, but these are the most crucial in terms of destructive change to the negotiating group.

How Do I Access the Policy?

You cannot. A glossy overview of the goals of the policy is available, but none of the federal core mandates are publicly defined. The federal core mandates and some regional/local variation are contained in secret federal Cabinet documents for each negotiation table under the oversight of a Federal Steering Committee made up of inter-departmental officials reporting to the federal Cabinet.

Who can participate in the Comprehensive Land Claims policy?

While the Specific Claims policy deals with specific parcels of reserve or historic treaty lands that were lost, the Comprehensive Land Claims policy is meant to deal with the total territorial base of an Indigenous nation. So why are “Aboriginal groups” negotiating at the tables as bands, or clusters of bands, without consent from the nation? For some Indigenous nations Aboriginal Title is held at the community level; for other Indigenous nations Aboriginal Title is held at the national level. The federal government seeks to negotiate with “willing partners” either as an entire Indigenous nation or “Aboriginal groups” of an Indigenous nation. The Supreme Court of Canada has stated that the proper title-holders that exercise territorial rights are Indigenous nations and the historical, cultural, social and political organization of each Indigenous nation is different.

THE Process

Those negotiating on your behalf may also have negotiated the process of undertaking community consultation and gaining community consent. Then again, there may be no established guidelines negotiated that specify how the process must unfold to be considered valid.

Here are some questions you have a right to know the answers to:

- How many meetings a month must be held to keep community members updated on negotiations?

- What are the agreed protocols for posting notices?

- For those who cannot attend meetings, what steps are being taken to ensure information is circulating to all community members?

- What process is in place to give community members a balanced account of the negotiated agreement, especially given the complexity and inaccessible legal language of the agreement?

- What measures are being taken to ensure progress in negotiations, so that money is not being misspent that the community will be on the hook to repay?

- What are the eligibility criteria for “members” or “beneficiary status” and what percentage of the population of eligible members must vote to ratify the Agreement in Principle? Is this number the same for the Final Agreement?

- How many votes, by percentage, must be cast for the Agreement in Principle or Final Agreement to pass?

If there are no answers to these questions (i.e. your negotiators failed to address these procedural questions), then you have some room to demand a say in the criteria for the process of negotiations. Understanding and shaping the process of land claims negotiations will help you strategize on how to support, defeat, or influence the vote.

What kind of transparency is required in the negotiation process?

According to Canada: Section 13 [4.2] Ratification: “Canada requires clear and adequate evidence that the negotiated agreement is acceptable and that the members of the Aboriginal group have given consent to the agreement. Ratification processes can be negotiated, but Canada must be satisfied that all members have an opportunity to participate, that all relevant information is available to eligible voters, and that ratification procedures are transparent, fair, democratic and recognized as binding.”

If the community has no access to information regarding current negotiations, does this change the legal status of the vote? Can this nullify the vote?

The negotiating group must argue that a lack of consultation nullifies the vote because the stakes are too high for a small group to push through extinguishment of the community’s land rights. They could refer to Canada’s own standards, as stated above, in order to persuasively argue that the ratification procedure lack transparency, fairness, and democratic standards. Furthermore, if every consultation presented only the positive gains of the settlement and failed to mention the core federal mandates outlined above or other negative outcomes, you can make the case that the process lacked transparency and integrity.

Can those opposed to the treaty remove yourselves from the process? What happens if you do not vote?

Then you have no modern treaty rights – you lose your status in the corporation.

THE LOANS

If you vote “no” to the treaty, are you still on the hook for the millions of dollars your treaty group borrowed in loans?

The negotiating group must argue against being on the hook for this loan money and there is at least one tool at your disposal. The Xaxli’p First Nation signed a framework agreement in November 1997, but they had a change of heart and pulled out 10 years later. Indian and Northern Affairs Canada almost immediately began sending them a bill for $27,249 / month to repay their almost $2.5 million loans, which would have bankrupted the band and sent them into third party management. The band filed a submission with the United Nations Committee for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD). Canada was forced to respond to CERD and put Xaxlip’s loan in abeyance.

THE AGREEMENT IN PRINCIPLE (AIP) AND FINAL AGREEMENT (FA)

Is the AIP legally binding?

No. But it signals that you are ready to continue the path towards signing a Final Agreement. It also defines the limits of what can be in the Final Agreement. Big changes in the final round of negotiations are extremely difficult to obtain.

What happens if your community pulls out of the treaty agreement or votes no?

The government and your negotiators will want you to vote in favour of the AIP because a “no” vote is a vote of non-confidence that will discredit their efforts. Therefore, the pressure to vote for the treaty will continue to increase. If the community votes against the AIP, the government can immediately try to collect loan repayments borrowed by your band for negotiations. Or, they may try positive inducements, like offering money for a “yes” vote. But ultimately, what happens when you vote “no” against the treaty is that you save your land for your grandchildren and for future generations by not signing away most of it to the province in which you are based.

TITLE & RIGHTS

How does the Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia (2014) Supreme Court of Canada decision affect modern treaty negotiations across the country?

The Tsilhqot’in decision, and the Delgamuukw (1997) decision before that, should have led to major changes in the land claims policy based on what the Supreme Court of Canada said about who holds title to lands in BC. The Supreme Court of Canada in both cases said that Indigenous peoples hold underlying title to lands based on their prior occupation to assertions of Crown sovereignty and settlement. If Indigenous title underlies Crown title, then why is the burden of proof for showing title on First Nations? Should it not be on the provincial Crown? The Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs issued an analysis in 2016 following the Tsilhqot’in decision, finding inconsistencies between the policy and Section 35(1) rights in light of the Supreme Court of Canada decisions.

What negotiators say

If you register land in the provincial system you will still have authority, jurisdiction, and law-making authority over land.

The reality

Your authority, jurisdiction and law-making authority will be subject to provincial and federal regulation and oversight.

Residents will have “clear title” and they will be able to sell their land on the open market and get mortgages.

There is no market for most reserve housing in their current state and you can attract and attain investment presently to your land with 99-year leases.

Province and Canada will continue to fund all current programs.

Funding will gradually ease off over a 6-8 year period.

You do not give up your Aboriginal rights. You will also continue to be eligible for all programs and services available to all Aboriginal people, and you will continue to be Status Indians.

This is a blatant lie. You will be expected to start earning money from own-source-revenue and property tax.

You do not have to extinguish your Aboriginal title.

The legal jurisprudence that protects Aboriginal title lands will no longer apply on your fee simple lands.

A BETTER WAY

What alternatives exist to the comprehensive land claims policy?

- Creation of a new policy that recognizes and affirms Aboriginal title;

- Recognition and Implementation of inherent Indigenous laws and jurisdiction in planning and management of lands, territories and resources;

- Economic rights and environmental protection to broader treaty territories.