On October 12, 2015, the day of Indigenous Resistance, Carlos Pérez Guartambel entered Ecuador with a Kichwa passport. It caused confusion for Immigration authorities who said “We have never seen such a passport before.” Not long after, they determined that it was “not a valid document.”

Guartambel, an Indigenous lawyer and president of The Confederation of Kichwa Peoples of Ecuador (ECUARUNARI) invoked the Ecuadoran Constitution to defend his Kichwa passport. “The first Article of the Constitution establishes Ecuador as a pluri-national state, and over twenty articles recognize collective rights,” he argued. To issue a passport, he insisted, is a core dimension of Indigenous Peoples’ right to self-governance and self-determination.

Immigration authorities did not know what to do. After 30 minutes of hesitation, officials accepted the Kichwa passport as a form of ID, stamped Guartambel’s immigration card (not the passport) and allowed him to enter Ecuador.

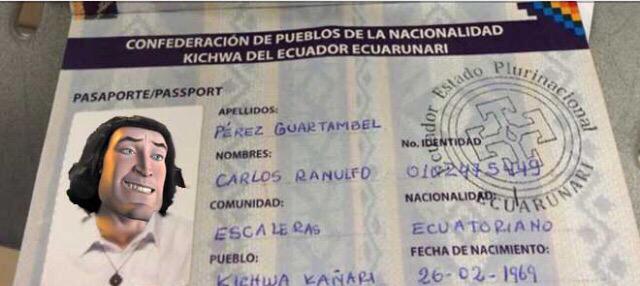

Within a few hours, however, Ecuadoran state officials reversed themselves and denied the validity of the Kichwa passport. This can be seen in a video released by the Department of Immigration in the Ministry of the Interior. Minister Serrano ridiculed the Kichwa passport as a “fantasy” on Twitter, posting a montage of the Kichwa passport with the portrait of a cartoon character. The Foreign Affairs Minister followed, and social media was invaded by official aggressions ridiculing Indigenous political authority.

El pasaporte de fantasía presentado por el señor Pérez Guartambel, me gano el personaje!! Vale la pena una risa!!

Unofficial Translation: The fantasy passport presented by Mr. Perez Guartambel won him the character! it is worth a laugh!

— José Serrano Salgado (@ppsesa) October 14, 2015

The government’s aggressiveness indicates that Indigenous passports are not mere acts of fiction. To the contrary, they constitute legitimate practices of self-determination. The use of a Kichwa passport to enter Ecuador marks a milestone in Andean politics.

It was the first time that Indigenous authorities issued a passport in Ecuador. Indigenous movements celebrated the episode as a victory in the name of self-determination. The press gave extensive national coverage to Guartambel’s October 12 arrival with his Kichwa passport in hand. Later that afternoon, the Council of Government of ECUARUNARI, an organization founded in 1972 by 18 Indigenous Peoples and representing 14 different nationalities, met in Quito to distribute over 300 passports, including one to Salvador Quishpe, the Governor of the Amazon Province of Morona-Chinchipe. During the passport ceremony, the Kichwa leadership insisted that Indigenous passports were as valid as ancestral medicine, inter-cultural education, and Indigenous justice–all recognized in Ecuador.

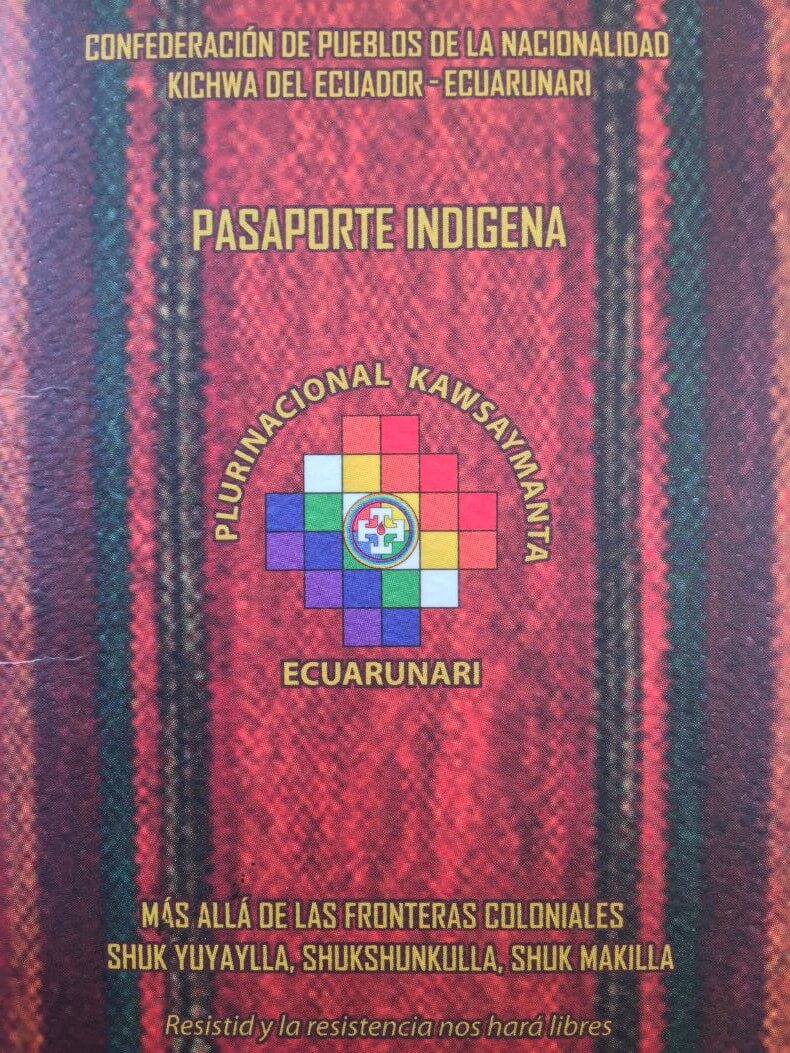

The Kichwa passport itself represents Indigenous philosophy and politics. The cover features a Chakana, the millenary Andean cross representing a complex concept of the cosmos, framed by text in Kichwa and Spanish – “Plurinacional Kawsaymanta” and “Beyond colonial borders-resist and resistance will make you free.”

Front and Back cover of the Kichwa Passport (Photo © Manuela Picq)

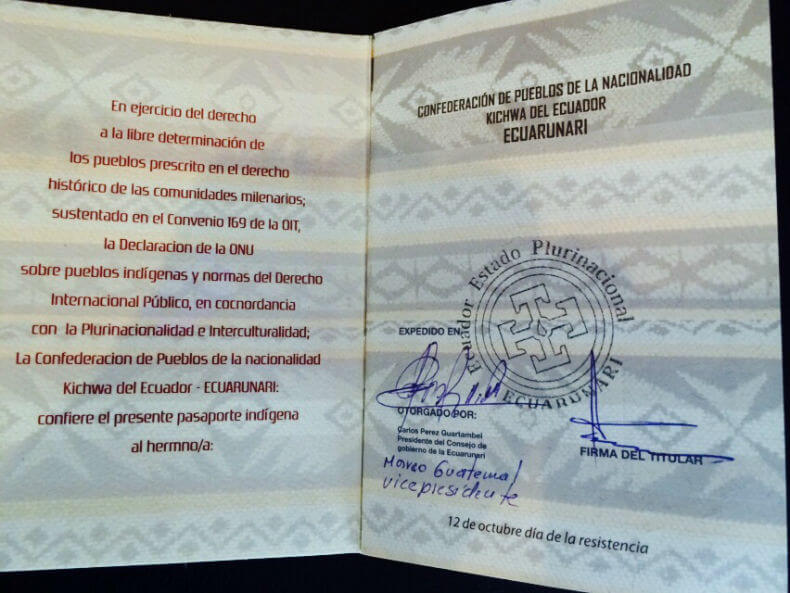

On the passport’s back cover are ECUARUNARI’s flag and signs of Andean cosmovision, alongside the names of the 18 peoples that constitute the organization. “A people who forgets its past is a people with no future.” Inside, the opening page cites the rights to self-determination articulated in the International Labour Organization’s Convention 169 and the UN’s 2007 declaration on the rights of Indigenous Peoples. ECURUNARI’s stamp validates the passport and the holder’s identity.

Inside the Kichwa Passport (Photo © Manuela Picq)

Pages are decorated with background images of historical leaders like Tupak Katari, Manuela León, Dolores Cacuango, and Lázaro Condo, with their sayings printed in Kichwa and Spanish. Inside the back cover a text reminds us that Indigenous peoples constitute about 5% of the world’s population and play a stewardship role in preserving about 85% of the world’s biodiversity.

The Kichwa passport on its own represents the unique cosmovision of the Andes; yet, it becomes even more relevant for its place in broader Indigenous battles involving Indigenous passports used as acts of resistance in the face of colonial states.

Today’s Kichwa passport echoes the case of Aboriginal passports, when in 2010 Australia’s Aboriginal Provisional Government (APG) issued its own passports for Sri Lankan asylum seekers in the face of Australia’s Commonwealth Government detention of the “Merak Refugees,” thus willfully refusing to fulfill its international obligations under the 1951 UN Refugee Convention. The issuance of Original Passports not only condemned the inhumanity of Australia’s asylum policies, it also represented an alliance between migrants and first peoples pushed from their lands. Passports expressed the political authority of native peoples who do not recognize state legitimacy as the sole, sovereign power.

The initiative for a Kichwa passport is also anchored in a specific case of immigration policy. The idea emerged when Guartambel’s partner had her visa suddenly revoked and she faced deportation last August accused of “participating in politics.” Manuela Lavinas Picq, a French-Brazilian journalist and academic, was beaten and arrested along with Guartambel at the peaceful protests of August 13 and was subsequently detained as an illegal immigrant. Her expulsion from Ecuador was part censorship, part political vendetta against the Indigenous leader. The original idea to give Picq a Kichwa visa to enter Indigenous territory evolved into the creation of a Kichwa passport in a country officially defined as a pluri-national state.

The 2008 Constitution defines Ecuador as a pluri-national state, establishes the concept of universal citizenship, and guarantees collective rights to self-determination. President Rafael Correa even declared himself opposed to state borders and immigration policies designed to exclude migrants at the 2015 UN General Assembly. In practice, however, Ecuador’s Indigenous Peoples continue to be pushed out of their territories and immigration policies are manipulated to silence and censor political dissidence.

In Australia, Robbie Thorpe from the Aboriginal Tent Embassy spoke of the hypocrisy of a colonial state that claimed authority to deny asylum to a land where it never exercised legitimate legal sovereignty. Migrants today face the same racist and imperialist policies that have dispossessed Aboriginal people for centuries. In Ecuador, Guartambel asserted his people’s authority to issue passports to consolidate the shared sovereignty of Indigenous and non-Indigenous nations. In both Australia and Ecuador, the power to issue passports is to challenge state-defined borders.

As a diplomatic act, Kichwa passports evoke the long history of Indigenous passports in Canada and the US. In 1923, and in what was perhaps the first recognized use of a Haudenosaunee passport, Deskaheh made his own voyage from Turtle Island across the Atlantic Ocean in a bid to further Haudenosaunee nationalism. His destination was the League of Nations in Switzerland, where he lobbied for national recognition so that his people would be protected from the meddling of the Canadian government in their affairs in direct contradiction of the principles established in the Two Row Wampum Treaty and other international agreements. Though ultimately unsuccessful, the Netherlands insisted on Deskaheh’s petition being presented before the League of Nations despite backlash from Canada and allies such as Britain, who would have otherwise been successful in preventing its presentation from being considered. Similarly, in 1977, the Netherlands supported calls for international recognition of Haudenosaunee passports despite adamant international opposition. At that time, twenty-eight states agreed to accept Haudenosaunee passports, though this number has fallen in recent years due to countries (including the Netherlands) reversing their position on the matter.

The Haudenosaunee passport gained center stage in 2010 when the Iroquois Lacrosse team tried to use it to attend the World Championships. The team missed the championship because the British government refused to recognize the passport issued by the Six Nations Confederacy, even after U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton intervened in the case. Unable to enter to Canada on their own passports, the delegation ended up driving back to Canada after taking a flight to Plattsburgh, N.Y. Iroquois women reiterated the stand for native passports in 2015. The Haudenosaunee under-19 women’s lacrosse team withdrew from the FIL U19 Women’s World Championship in Edinburgh, Scotland, because they were forbidden to use Rotinoshonni-issued passports.

While these efforts had limited impact, the promotion and recognition of Indigenous rights in contemporary world politics is a major battle for legitimating self-determination. The Six Nations Confederacy points out that the notion of self-determination goes back to their first treaty with the Dutch government in the 17th century, called Guswhenta, or the Two Row Wampum belt treaty. Similarly, ECUARUNARI’s decision to list the ILO Convention 169 and the 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples inside Kichwa passports reminds states of their legal obligation to recognize Indigenous self-determination in the here and now.

A core question is what passports actually mean in today’s world. More than a travel document, they express national identity and one’s place in the international society of nations. It is in that sense that Indigenous Nations issue passports, contesting the obligation to hold a colonial passport for international travel. They are the primary way in which the vast majority of people prove and express their citizenship as a form of external constitutive relation. Legal and other scholars focusing on self-determination tell us that this external recognition and pressure between states has been a large part of the reason why the claims of Indigenous Peoples, at least in the Americas, New Zealand, Australia, have been gaining force since 1945.

It is in this sense that a Kichwa passport embodies important Indigenous struggles for political recognition. It is not merely a token gesture. Rather, it is a legal claim that powerfully contests centuries of colonialism. It is the practice of self-determination.

Manuela Lavinas Picq is a scholar of International Relations. She is professor of International Relations at Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ), Ecuador, and former Research Fellow at desiguALdades.net, Freie Universität Berlin.

Marc Woons is a philosopher whose work focuses primarily on contemporary Indigenous-state relations. He is currently a researcher at the Research in Political Philosophy Leuven (RIPPLE) Institute at KU Leuven, Belgium.

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.