Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities are stewards of natural resources and nature. We have been conserving our territories for thousands of years. Each indigenous community has its own territory. For indigenous nomadic pastoralists our territory consists of summering grounds, wintering grounds, migration routes, stopovers and mid-way stations with different ecological, social, economic and cultural assets. These assets include forests, rangelands, wetlands, lakes, rivers, coasts, seas, and many other types of ecosystems and wildlife.

A key approach available to Indigenous communities to protect their territories and strengthen their territorial rights is called Indigenous Peoples’ and Community Conserved Territories and Areas (ICCA). ICCAs were defined by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), an international organization composed of civil society groups and governments with observer and consultative status at the United Nations.

An ICCA recognizes the territorial rights of Indigenous communities and their role in biodiversity conservation. ICCAs do not have to be recognized by local or national governments, but getting such recognition can help communities and governments to strengthen Indigenous Peoples’ control over their territories and enable them to prohibit harmful activities such as industrial logging, monoculture tree plantations, mining, or construction in such areas.

These days, GIS digital maps are proving a really useful tool for Indigenous Peoples to delineate their own customary territories, which are often different from official maps. Many local communities are learning how to use the technology and working with experts in participatory mapping activities. Participatory GIS has turned into a sort of “counter mapping” enabling local communities to make their own maps and models, and using these for their own research, analysis, assertion of rights and resolution of conflicts over land. Such mapping exercises also motivate community members to keep on defending and conserving nature and their territories as they have done for thousands of years, in spite of the difficulties they encounter.

The Centre for Sustainable Development (CENESTA), a Civil Society Organization working in Iran and a founding member of IUCN, has been advocating for ICCAs for decades. This photo-essay captures CENESTA’s experience supporting Iranian Indigenous communities in mapping out their territories.

Nomadic pastoralists from the Qashqai Tribal Confederacy cross a bridge on their traditional migration route. They migrate once a year in search of new pasture for their animals. Their migration route is considered one of the longest and most difficult.

Indigenous nomadic pastoralists from the Lak Tribal Confederacy on their migration route.

An Alachiq is an elegant traditional tent used by the nomads of the Shahsevan Tribal Confederacy from northern Iran.

Indigenous women from the Shahsevan tribal Confederacy camped in their tents (Alachiq) in their summering grounds. They display a two-humped Bactrian camel. The Shahsevan have an age-old relationship with these camels, which have served as transport on their migratory routes for centuries. The Shahshevan believe that the camels bring blessings to their lands, which are an important habitat of the Bactrian camel.

Indigenous territories in Iran are increasingly threatened, as in other parts of the world. Pictured here is the encroachment of farms and orchards into nomadic rangelands. This decreases rangeland areas and endangers the livelihoods of the pastoralists. Participatory maps can help to determine invasions, barriers and land use changes in Indigenous Peoples’ territories. Such maps can help communities to advocate for their lands and rights.

Industrial development within indigenous nomadic territories creates pollution, destroys rangelands and pasturelands, and harms human and animal health.

Urban development into nomadic territories creates obstacles for migration. Communities are forced to migrate in trucks and the their livestock face many risks on the road.

Concrete roads hamper nomadic migration. Alternative migration in trucks causes pastoralists to arrive prematurely at their summering or wintering grounds, much sooner than the natural vegetation is ready for their arrival.

Community members analyzing a map during a Participatory GIS (PGIS) mapping exercise. PGIS

places control on access and use of culturally sensitive spatial data in the hands of those communities who generated it.

Community members working on hand sketched maps. Through such maps, they can delineate their territories which consist of both ancestral domains and current areas.

Community members using topographic maps. Such mapping exercises usually depend on the communities and how familiar they are with maps. In some communities hand sketched maps are the best way to start working on territories, while others are open to printed and topographic maps.

Community members using Google Earth. For those communities that start working on hand sketched or printed maps, CENESTA carries out various workshops to match the print maps to Google Earth until the exact boundary of the territory is known and is acceptable to the community.

Pictured here are women and children in the mapping activities.

A key to success in the mapping approach is participation of all generations from the communities. All of them have different knowledge. Elders know best about ancestral domains, while men are well informed about summering and wintering grounds, and women may know more about medicinal plants and other ecological assets. The younger generations know a lot about incursions into their lands. All of them know well of migratory routes. It is important to include children in such processes so they can learn from their elders and fulfill their future responsibilities for conserving and defending their territories.

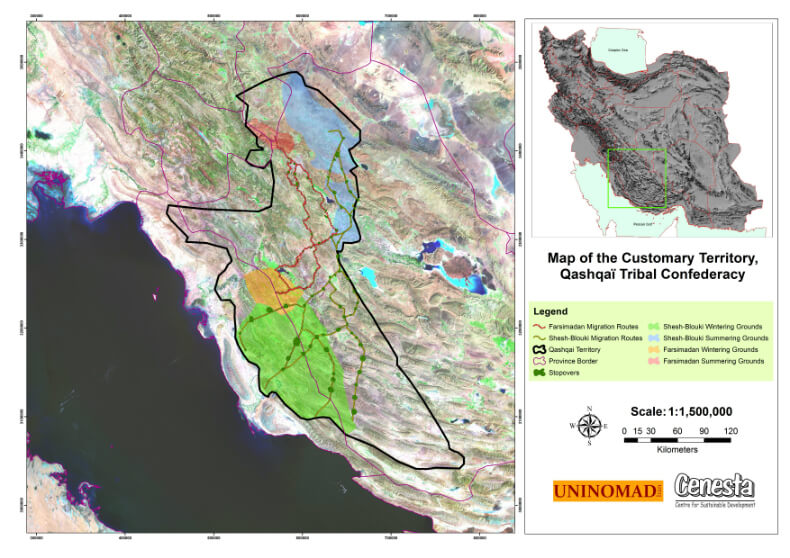

This is what a completed GIS map of a community territory could look like. Pictured here is a map of the Qashqai tribal confederacy territory.Facilitator for preparation of map: Ghanimat Azhdari

Community representatives in negotiation with government officials. They compare their maps with governmental maps finding inconsistencies. As they have demarcated all the threats and incursions into their territories, they have a powerful tool to advocate for their removal.

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.