Revolution, counterrevolution, or coup d’état? The turn of events in Bolivia after the October elections has been so rapid, surreal and tragic that some of us are still adjusting to our new reality. There are so many opinions inside and outside Bolivia, most based along ideological lines, that try to fit Bolivia into a predetermined role. Bolivia, however, remains a complex and divided country, along ethnic lines as well as the vast geography of a country three times the size of Germany. From the frosty Andes plateau that stretches across the backbone of the country with its “white city”, the historic capital Sucre, home to the Supreme Court and the country’s judiciary; its rivalry to the de facto capital La Paz, home to the congressional assembly and presidential palace where Evo Morales ruled for almost 14 years; and Santa Cruz, the business capital located in the agricultural breadbasket in the east where the protests began.

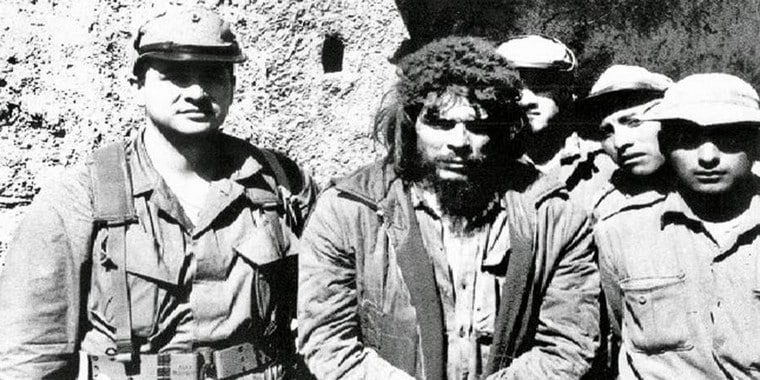

Bolivia is a land that has always been hard to understand. Che Guevara came to Bolivia to start a continental Revolution in the ’60s and was captured and executed. So why did the oppressed Indigenous Bolivians not rally behind this iconic white savior back then? To start, Bolivia already had a Revolution, a decade before in the 50’s, which brought Land Reform, citizenship to the Indigenous, the right to education, and more. However, what is more important to note about Guevara’s arrival is that he did not arrive to a Costa Rica, or to a monolingual Latin-American country. He arrived to a Bolivia, when the most spoken language was still Quechua. Bolivia was probably the last former Spanish colony in the Americas to have Spanish successfully imposed as the predominant spoken language, and not until the ’70s.

The irony of Che Guevara’s end, when he became a martyr, was that an indigenous Aymara soldier (trained by the U.S.) found him; of course his white general took all the glory. So who joined Che’s guerrilla group? Mostly urban white and mestizo middle-class Bolivians; the only indigenous member was the porter. Bolivia was hard to read back then and now. Anyway, the competing narratives and alternative storylines about the Electoral Fraud/Military Coup in the aftermath of the October elections are well known. I just want to share my views on the main characters and my experience as an Aymara-Bolivian from La Paz, who worked as a diplomat for the Bolivian Foreign service from 2011 to 2017, first in the Bilateral Relations Office in charge of the USA desk in La Paz and later at the Permanent Mission to the United Nations Organization in New York, in charge of the 2nd Committee of the United Nations General Assembly: Sustainable Development and Macroeconomic Policy and also as Bolivia’s interim Political Coordinator to the Security Council between 2016-2017. I hope this might provide some subtle insights.

“The irony of Che Guevara’s end, when he became a martyr, was that an Aymara soldier (trained by the U.S.) found him; of course his white general took all the glory.”

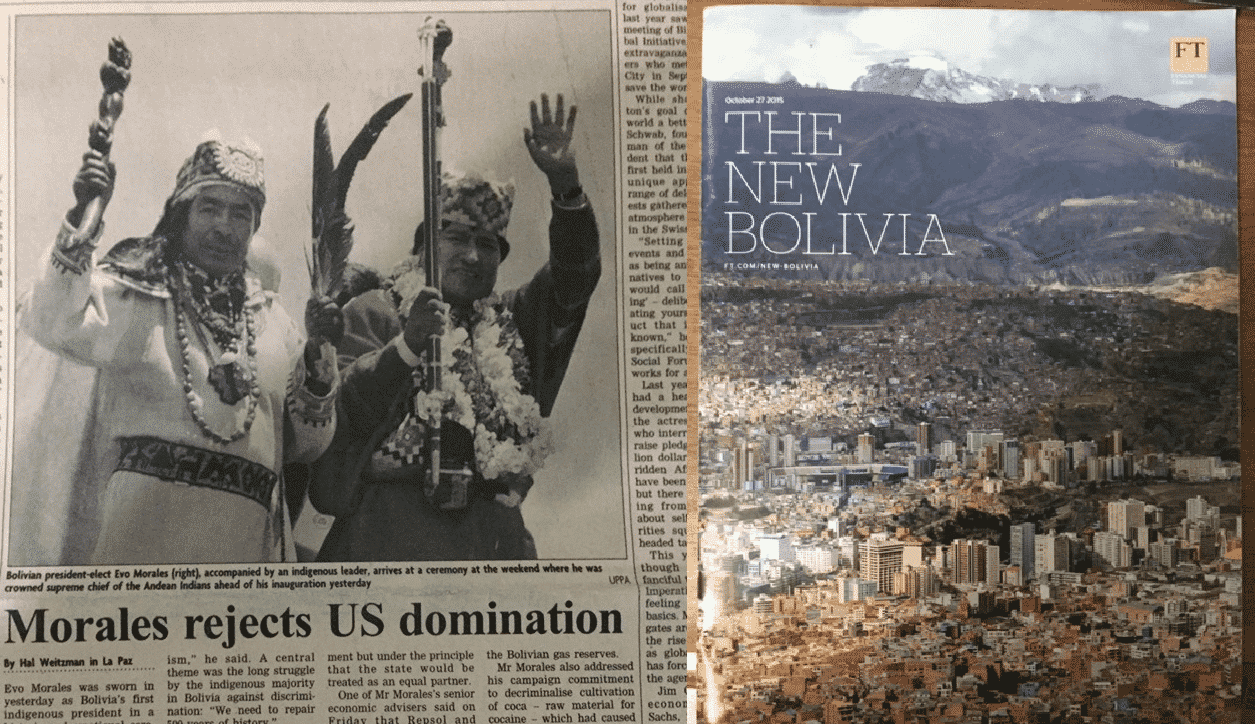

The last time Bolivia made it to the front page of the Financial Times (that I remember) was in 2006. Evo Morales, an Aymara Indian, had been elected as our first Indigenous President, in the most Amerindian Nation of the Western Hemisphere. He brought hope of social justice to the Indigenous in an extremely unequal and racist country (politically and economically). He was the product of the social movements and indigenous struggles from 2001 (the Water War) to 2003 (the Gas War), much like Chile today, but with a strong ethnic element that ended with the Aymara Massacre of more than 70 people in El Alto, remembered as Black October 2003, and the collapse of the Neoliberal State. His government actually delivered on the demand of refounding the nation and drafting a new Constitution. He was our Nelson Mandela. Sadly he ended up turning into Bolivia’s Robert Mugabe. He resigned on Nov. 10 and fled into exile to Mexico on Nov. 12, 2019, after almost 14 years in power. He could easily have been the best president Bolivia ever had. When did it all start to go downhill?

He was our Nelson Mandela. Sadly he ended up turning into Bolivia’s Robert Mugabe. He resigned on Nov. 10 and fled into exile to Mexico on Nov. 12, 2019, after almost 14 years in power. He could easily have been the best president Bolivia ever had. When did it all start to go downhill?

As former Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva mentioned, Evo’s mistake was running for a 4th term, when the Constitution had two term limits. His first terms enjoyed the support, participation and good will of social/indigenous movements as well as progressive intellectuals, feminists, environmentalists and other activists. The project was to decolonize the State through a “Proceso de Cambio”: Process of change. The economic policy was sound and pragmatic, record GDP growth rates, low inflation, better natural gas contracts, and redistributive social policies, targeted to the poorest. Poverty was cut in half and millions entered the middle class. I saw first hand at the United Nations how indigenous symbols, traditions and demands became a banner for the new government in diplomacy and at the multilateral organizations: The human right to water, the rights of Mother Earth, and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). And for the first time the country was genuinely sovereign from the IMF, the US or the EU.

In the 2014 election Evo was extremely popular, reaching two-thirds of the Congress, and virtually controlled all the Powers of the State. In his own words, Evo Morales said, “Independence of powers is a tool of Imperialism” (Always referring to U.S. Imperialism). By then he had built a strong clientelist political machine with himself at the center and no successors. He turned increasingly authoritarian. His party failed to build a movement and had to depend on the classic cliché of the Latin American “Caudillo” with a strong cult of personality.

Essential to the construction of this political machine was his main ideologue and vice president: Alvaro García Linera, a white Bolivian, Marxist self-taught intellectual and former guerrilla fighter. His vision and “his people” within the government became hegemonic; the “revolution” had taken over the state. Evo claimed that the social movements had asked him to run again, but the social movements were co-opted or had vested interests, like the coca growers. Any dissent or self-criticism within the party was silenced, and many progressive intellectuals gradually left. Any potential Indigenous successor was beheaded (not literally, but politically) and Evo was convinced that he was irreplaceable. His development policies were extractivist: fossil fuels, mining, hydroelectric dams over Amazonian rainforest. He reached an alliance with the elites of Santa Cruz, the eastern business capital and major trading hub for natural gas with Argentina and Brazil, to promote large-scale agricultural industry, deforestation and biofuels.

The Vice-president had accused foreign NGOs of brainwashing the Indigenous into protecting the rainforest and expelled these NGOs. Evo began to contradict his discourse of protecting Mother Earth and the Indigenous. The repression of indigenous peoples marching against a road that would cut through the Isiboro-Secure National Park and Indigenous Territory (TIPNIS) in 2011 was a turning point and a clear sign of the decline. These policies reached a peak with the burning of over 5 million hectares of forest in Chiquitania, the vast Pantanal wetlands and the Amazonian basin in 2019 to expand the agricultural frontier.

“Morales Sworn In. First indigenous Bolivian president cautions US.” Financial Times: Monday 23, 2006

The Resistance came from an unprecedented social movement of Millenials, young Bolivians, many of them students, who had only ever known one president: Evo Morales and his increasing authoritarianism. These were not the traditional social movements from 2 generations ago, this was a new wave that could be considered a “Bolivian Spring”. Their ranks swelled with progressives and middle class Bolivians to over two million protestors on the streets in cities across the country very angry at reports of systematic electoral fraud, later confirmed by the Organization of American States. These Bolivian voices were sidelined by the international media, even as they simultaneously championed student protestors in Ecuador, Chile, and Colombia, who demanded similar things: accountability from their governments, economic opportunities and against a patriarchal state and the abuse of power of the ruling classes.

After the “rapid count” of the CNE (National Electoral Commission) was stopped on election day Oct. 20, university students in the city of La Paz started to protest in front of the Electoral Tribunal. They were convinced that there was fraud and that Evo had stolen the vote for the second time (the first time being Feb. 21, 2016, when Evo Morales lost a referendum on a re-election amendment to the Constitution). Evo dismissed the students as being paid with money or grades. The blockades just increased in the cities, especially in upper and middle class neighborhoods like Zona Sur. Entire families emptied their homes to form blockades on the streets of their neighborhoods with flags and cords known as pititas that inspired its own hashtag #pititas while inspiring derision from Evo Morales, who considered the pititas pitiful. I thought they were going to get tired, but the movement only got stronger in all the main cities across Bolivia, and other groups such as teachers and medical doctors joined in. In neighborhoods like mine there were night marches, and the chants were clear about why the middle class, millennials, and progressives in the cities were protesting. The chants were:

– “This is not Cuba nor Venezuela, this is Bolivia, respect Bolivia”

– “Dictatorship No, Democracy Yes”

– “I do not want to live in a Dictatorship like Venezuela”And the famous chant :

-“Quien se rinde?” (Who gives up?)

-“Nadie se rinde!” (No one gives up!)

-“Evo de Nuevo?” (Evo again?)

-“Huevo Carajo!” (F%$^ No!)

Evo underestimated these new political actors and their peaceful protests. He would mock the protests, saying that he could give them seminars on how to make a real blockade like the mass mobilizations he organized of “Cocaleros” (coca growers) that make up his base. These new generations of millenials and digital natives that started to vote during the longest government we ever had, organized themselves by social media and were angry at the attempts of Morales to cling to power. They resembled the Hong Kong students; they were convinced that Bolivia was heading towards a totalitarian regime and were fighting for Democracy. They were from different ideologies including the left and many were environmentalists who had protested the burning of the Chiquitano Forest. The more active were from the UMSA, the main State University. Also, they were not only from La Paz, since a big part of the UMSA students come from El Alto. These groups blockaded the country for 21 days until Morales resigned, and considered this their victory.

On November 10, after 21 days of civil protests following the controversial results of the October elections and the OAS report which contained irregularities in the electoral process, Evo Morales resigns and international news outlets such as the BBC start covering the unfolding crisis

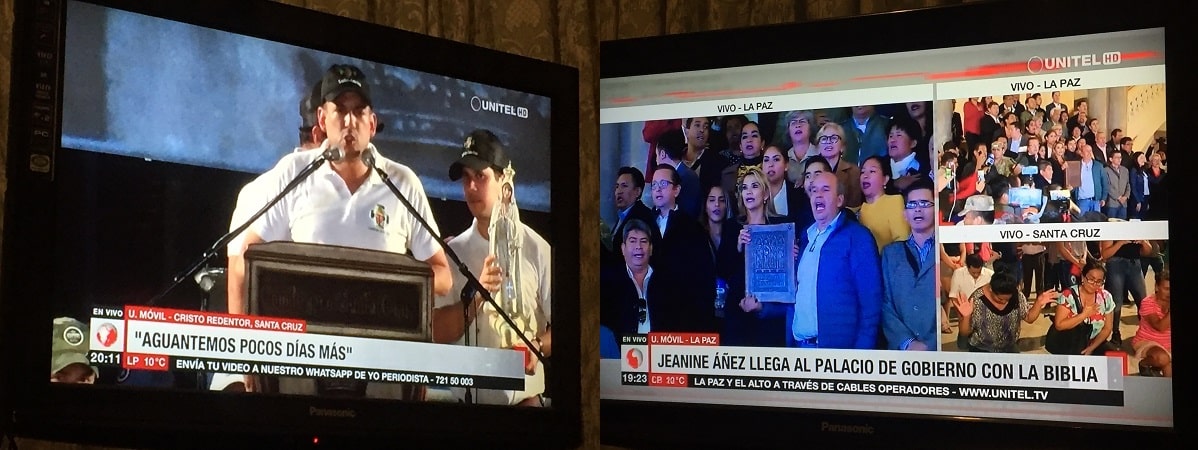

Fernando Camacho was a virtually obscure character until he rose to fame on the back of the protests in Santa Cruz, emerging as a young and daring civic committee leader, calling for massive protests across city armed with the Bible and prayer. His rallies (cabildos) were monumental, Hollywood style, like a scene from the movie Independence Day. He attempted to fly to La Paz three times, but each time he was blocked from entering the city by the supporters of MAS (Movimiento al Socialismo: Movement toward Socialism, Evo Morales’ ruling party), who occupied the airport trying to stop him. He allied himself with the Civic Committee leader of Potosí, Marco Pumari, giving the committees a national presence as a unified front. His rallies in Santa Cruz were impressive, and Camacho dared to give an ultimatum to the President to resign.

During its long government, the MAS had managed to form alliances with the Santa Cruz elites, who became incredibly wealthy during Evo’s presidency. It was not enough. The MAS also underestimated Santa Cruz, the new economic capital of the country. The Santa Cruz-based opposition had become increasingly angry at the tendency of the Morales government to concentrate resources and power on the central government at the expense of state autonomy, and at the accusation that they were separatists; but they were especially furious at the burning of the Chiquitano forest in July and August, and the refusal of the government to call for international help.

On the day that Evo Morales tendered his resignation as president of Bolivia, Fernando Camacho entered the empty Government Palace with a Bible and a Cross, and fell on his knees. Fifteen minutes later, he claimed, Evo had resigned. Most of the civic leaders attended the proclamation of interim President Jeanine Añez, cheering from the balcony of the Government Palace. Fernando Camacho was holding a huge Bible, as if the religious demagogue were mimicking a mythic scene from history when the Spanish Conquistador Francisco Pizarro and Father Vicente de Valverde used a massive bible when they judged and executed the last Incan Emperor, Atahualpa.

Left: Fernando Camacho flanked by the Virgin of Cotoca, the patron saint of Santa Cruz.

Right: “Jeanine Añez arrives at the government palace with a bible”

The size of the massive protests in the cities across Bolivia increased by the day in the 21 days since the contested election. The government flew in coca growers and indigenous peoples to protect Plaza Murillo, the government square. The police were overwhelmed and had to protect the MAS supporters that came to La Paz and Cochabamba–coca growers and miners using dynamite in counter-protests to make noise–were outnumbered by the groundswell of popular protests against Evo Morales’ rule. The Police had to feed the counter-protestors. The Army did not go to the streets to repress the protestors and requested a written order from Morales to repress the city protests. At some point the Police in Cochabamba declared mutiny against Evo Morales and the other cities followed. They were exhausted and resented the treatment of the Government. There were already people dead in Santa Cruz and Cochabamba.

More opposition miners and students started to come to La Paz, from Sucre and Potosi. Many were kidnapped and beaten by MAS supporters in Oruro and in Challapata; armed groups and snipers shot at the caravans of protesters. These armed groups were not from the Bolivian Army or Police, implying foreign mercenary interference. This was one of the main reasons the Army suggested the President should resign. Up until this point on Nov. 10, the Army was not involved in any repression, and El Alto and the countryside had not taken part in the blockades and protests before the resignation.

After President Morales tendered his resignation, the MAS supporters started to mobilize. These were days of terror. Bolivia actually did not have a president for over 50 hours, no one to ask for security. It was really a social media war of fake news mixed with real events. The messages that went viral were different according to the part of the city. The government had hired squads of paid digital warriors, known as “guerreros digitales”, over a year ago. In La Paz, the messages were that the “MAS hordes” (hordas masistas) were coming down from El Alto or the countryside to burn houses and sack businesses. In fact the house of the Dean of the UMSA University was burned, as well as the house of a journalist from the University TV. over sixty-four buses of the city were also burned. In El Alto and the indigenous communities that surround La Paz the messages were about the extreme racism of Fernando Camacho, the bible bashing fanatic from Santa Cruz, that he had taken over as President and also that the people from La Paz were coming to attack El Alto.

The only TV channel that did not have State propaganda was the University TV, which broadcasted allegations of Electoral Fraud by statisticians, the Organization of American States, and the UMSA University. The State tried hard to cover all the airwaves. Evo Morales was in campaign mode for almost 14 years, using the resources of the State, traveling on his Helicopter or private jet to remote towns of the indigenous countryside inaugurating schools or soccer fields. Almost all the commercial TV channels had spots of the Ministry of Communication (the largest budget of the ministries running in the 100’s of millions $U.S.) playing every 5 minutes or less, trumpeting the achievements of his Cultural and Democratic Revolution.

After Evo flew to Mexico, the Indigenous campesinos, the MAS militants of El Alto and the coca growers from Chapare (the six federations of coca growers of which Evo was still the leader while being president) started pro-government counter-protests, with chants that included references to civil war. At this point it looked as if there were two Bolivias. Now the protests really turned violent.

From exile Evo played the Race card, positioning the crisis as a coup of the military and of the racist, fascist and coup mongering Right (la derecha racista, fascista y golpista), and encouraged his followers to besiege the cities (where most of the white and mestizo people live) to starve them of food and fuel. He called on them to topple the interim government, considered to be a right wing dictatorship. The only solution to pacify the country, according to Evo, was his return to Bolivia. His stronghold of coca growers in Chapare cut the natural gas pipeline that supplied Western Bolivia in Carrasco, Cochabamba, shutting down industrial activity and marched towards the city. The MAS supporters in El Alto took the main gas and fuel distribution center for La Paz in Senkata, with the danger of causing a mass chain explosion in the natural gas pipeline system of La Paz and El Alto. The Army and the Police had to intervene these protests that ended in over 30 deaths. The images of the indigenous counter-protestors who sacked businesses and terrorized citizens in La Paz and El Alto became a symbol of violence and terror. Police stations were burned, along with the house of opposition leader Soledad Chapeton, mayor of El Alto (MAS supporters had burned the city hall in 2016, leaving many deaths). Regional electoral courts and the houses of MAS politicians were also burned. It was all out war.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (ICHR) an organ of the Organization of American States issued a preliminary report on its visit to Bolivia between November 22 to 25, denouncing grave violations to Human Rights after the elections of October. The killings of Sacaba in Cochabamba and Senkata in El Alto were considered massacres by this commission. The interim government did not agree with the preliminary report, but invited ICHR to return with an independent investigation team for further investigation. The saddest part is that the city population no longer had much sympathy for the indigenous, as they did in 2003 after the Black October massacre. It was heartbreaking to see the people of El Alto, mostly Aymara, march towards La Paz with the coffins of their dead, and the Army firing tear gas grenades at them.

Many questions still remain. Were the Indigenous used as “cannon fodder” as they have been throughout Bolivian history in this modern day cold war between the Right and the Left?

Civil War? Was this a self-fulfilling prophecy? The seeds were certainly planted. It is enough to watch videos of the Vice President manipulating and patronizing the Indigenous people in their villages, talking at them like children: “we must support father Evo”, “if He leaves the sun will set and the moon will flee” “there will be crying”, “the Right will come and take away everything from our wawas (Aymara for babies)” “They will take your house away”. Evo Morales was sure the Indigenous would come to his rescue. Shortly after the protest began former Minister of Presidency, the infamous Juan Ramon Quintana, interviewed by Sputnik Russia, warned of a modern day Vietnam war if the Right ever took power.

What actually made an impression on me was an Indigenous woman who supported Evo, claiming that the k’aras (white in Aymara) had governed us for almost 200 years, and they won’t even let us govern for just 14 years.” (they actually believe that if Evo was not the President, there will never be an Indigenous President again, and it makes sense since that was true from 1825 until 2006). This shows how the country is divided, since anti MAS protestors could not understand indigenous supporters of the MAS.

Evo Morales when first inaugurated claimed that the “Indigenous” had come to take power of the Bolivian State for good, not as temporary tenants, but as the landlords, the legitimate owners. The problem was that He ended up convinced that only “Him” represented and was the “Indigenous”, not anyone else. He had also claimed that they would have to take him dead out of the government palace.

Left: An indigenous ceremony of inauguration at the ancient city of Tiwanaku, one of the first Andean Empires. Right: The New Bolivia was a paid conference to attract foreign investors to Bolivia, organized by the Financial Times in New York in 2015, when the economy was growing at its peak

The Evo Morales government truly changed history in Bolivia, because it started as an unprecedented government of the social and Indigenous movements. It is hard to measure, but regarding race relations, it restored dignity to indigenous peoples, because their cultural assets: the languages, the ways of life, the cosmovision and the traditions became official symbols of the state. In a sense it empowered all Bolivians, because of the “can do” attitude of the former President who had a strong belief that Bolivians could live to their full potential, by looking inside and at their ancient civilizations and to stop seeing themselves as less than their neighbors. From being one of the poorest countries in the Hemisphere, we saw possible natural gas connections to thousands of homes, mass public transport, an aerospace program and even a nuclear program. It was a success story of a democratic left wing government, while it remained democratic. For a small economy, by being sovereign from Western powers, I could witness how Bolivia had its own prominent voice at the multilateral international fora like the UN. Since we were not conditioned to Foreign aid, we could say anything we wanted to.

What I could rescue the most are the first administrations of Evo Morales, because the World expected an alternative to the Neoliberal or Capitalist system, in the midst of the ongoing major global environmental crisis. The environmentalist wing within the government was mocked as the “Pachamamistas” (Pachamama being Mother Earth) and it constructed a discourse of an alternative development model to Capitalism. This wing revolved around former Foreign Minister David Choquehuanca. The model was called “Suma Qamaña”: Living well in harmony with mother earth, which came from the Andean indigenous peoples. The inclusion of the terms “Mother Earth” and Development in “Harmony with Nature” was fought hard in intergovernmental negotiations of all major UN Sustainable Development Conference outcomes from Rio+20 to Agenda 2030 and it is present in the 17 Sustainable Development Goals. The concept of People’s’ Diplomacy was championed by holding alternative conferences with civil society, like the 2010 World Peoples Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth held in Tiquipaya, Bolivia in the face of the failure of the UN Climate Change conferences.

Just as the 52 Revolution had opened the gates of public office to mestizo Bolivians, the MAS government opened the door to many indigenous Bolivians into the State apparatus. This was especially a radical change in Ministries like the Foreign Relations Ministry, which was a bastion of traditional elites. Before the MAS, an indigenous person no matter how well educated even from a top foreign university could not get in the Foreign Service without the social capital of the white elites. I witnessed this first hand.

On the other side, the Marxist wing had a State capitalism model that worked with extractivist development policies. This was called “Economic Liberation”. The main theorist was Vicepresident Garcia Linera, who wrote many books and openly explained the different stages of the revolution, which had to go through capitalism, industrialization, and the rise of a new plebeian indigenous elite that would join the traditional white elite. The end will eventually be socialism. So, during the MAS government the size of government more than doubled, with the goal of building a strong state. Carlos Gil, a large private foreign investor/contractor with the government has called the Vicepresident “the manager” of the state. Many state companies were formed, from Brazil nut processing factories to a new State Airline. Unfortunately few of these attempts were actually profitable. The common practice of the state was taking over an existing market where there was a dominant private company, by taking the company out of business, through tax or legal resources, since all institutions responded to the Executive.

In the end, these two different views clashed, and the marxist wing became hegemonic. The state needed to generate funds for the social policies like the many conditional cash transfers to the poor, which included the elderly, children and pregnant women. In short the MAS government was a democratic and cultural revolution built by the social and indigenous movements in democracy that was eventually captured by a totalitarian model. The government saw itself as the “good guys”, so in their view they were allowed to remain in power by all means necessary.

Coming back to the October 2019 events, the Morales-García Linera government underestimated the ability of the middle classes and Santa Cruz to protest. They believed that having a stable and strong economy and a high GDP growth rate would compel the upper and middle classes to resign themselves to their fate of having the same president for almost 20 years or indefinitely, circumventing the constitution. Evo Morales looked up to strong leaders like Vladimir Putin. However, the shameless corruption cases, political persecution and abuse of power at all levels gave Evo the unmistakable image of a tyrant. They were sick and tired of his government. He expected another Black October massacre and for the Indigenous to save him, but it was clearly not 2003 anymore. El Alto was split; the hard-core MAS supporters had to terrorize the other citizens of El Alto by threatening to burn their houses, if they did not join the protests.

The interim government was clearly far right, but managed to get Congress to call for new elections and pacify the country at a high human cost.

The modern cable car system, an air subway: Mi Teleférico, which became one of the first mass public transportation systems of its kind, that inspired the Dominican Republic and even Disney world in Orlando, Florida. It stands as a symbol that an Indigenous president brought modernity to Bolivians

-November 24, 2019, Law 1266 is unanimously approved in Congress, which includes the MAS majority. Congress was never closed. This law nullifies the October 20 election because of Electoral Fraud, based on the report of the OAS. It also calls for new elections.

-December 7, 2019 At a MAS party congress in Cochabamba the historic CONALCAM (National Confederation for the Process of Change) is officially dissolved. The CONALCAM was the organization of the main social movements aligned with the MAS government. It was composed by CSUTCB (The Campesino workers union of Bolivia), COB (The Bolivian workers’ union), CONAMAQ (Confederation of Indigenous Ayllus and Markas), CIDOB (Confederation of Indigenous from Eastern Bolivia), Bartolina Sisa (Confederation of Indigenous women). Many of them became independent again or had two parallel organizations. At the congress the only remaining sector was the “Interculturales” or Coca Grower unions that staunchly support the MAS.

Bolivia is a land of epic revolutions and surreal landscapes. Unfortunately every structural political change in the country always pays the price of the working class in indigenous blood. There are many mixed emotions, much confusion and sadness at all the events and especially the deaths. The country is racked by post traumatic stress, and people fear that the social gains and the empowerment of Indigenous peoples will be taken away. It is like an upside-down world now. Evo and his government were so almighty that no one expected he would ever fall… I certainly hope the descriptions of these characters involved and events will help to better understand the context of what just happened and is happening in Bolivia. The simple binary discussion of whether there was a coup or not superficially conceals the pain, terror and confusion of a divided nation.

I finish full circle from the silver color line of the Cable cars (Telefericos) across the breathtaking view of the snow capped peaks of the Eastern range of the Andes (Cordillera Real), this line hovers above the sky in between La Paz and El Alto passing through the “Ceja” (the brow of the city and a landmark of El Alto), where an anachronistic gigantic steel statue of Che Guevara stands with his foot stepping on what is supposedly the neck of an American eagle (a symbol of US Imperialism), but what it really looks like is a Condor, the totemic symbol of the Andean Indigenous peoples (much as in baroque colonial art, the indigenous artisans would insert hidden messages). Around the statue plaza, the ever present informal economy of thousands of mostly Aymara merchants from poor to working class, selling anything that can be imagined continue their stoic everyday attempt to make a living ignoring the Che Guevara statue…

Gilber Mamani is an indigenous Aymara-Bolivian from La Paz, who worked as a diplomat for the Bolivian Foreign service from 2011 to 2017, first in the Bilateral Relations Office in charge of the USA desk in La Paz and later at the Permanent Mission to the United Nations Organization in New York, in charge of the 2nd Committee of the United Nations General Assembly: Sustainable Development and Macroeconomic Policy and also as Bolivia’s interim Political Coordinator to the Security Council between 2016-2017.

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.