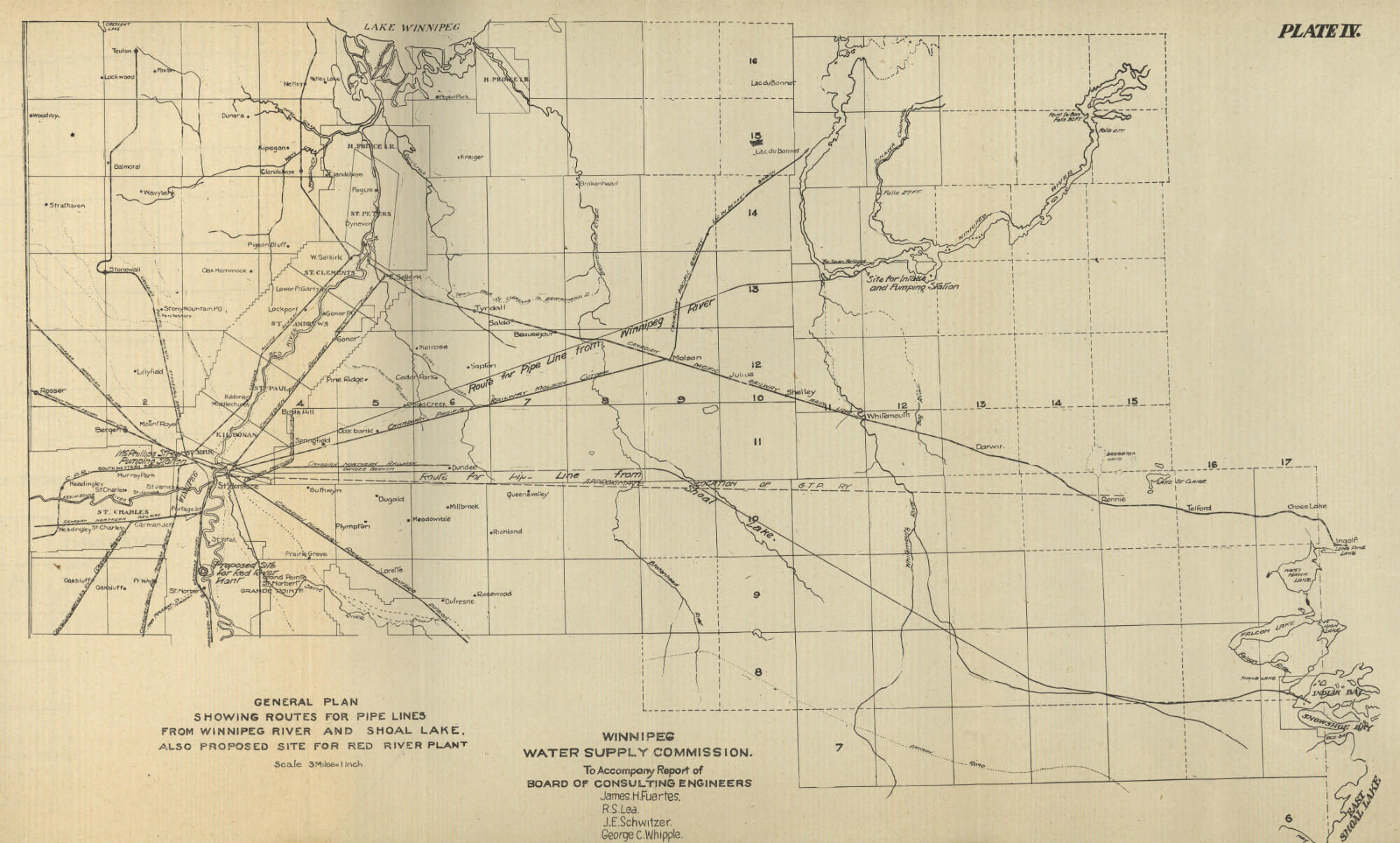

In 1914, Winnipeg was the third-largest city in Canada, out-growing its rivers and wells for potable water. City fathers cast their eyes eastward, to Shoal Lake, for a solution. It was simple: build an aqueduct from Shoal Lake to Winnipeg, and let the water flow. For most of Winnipeg’s citizens that’s where the story ends. For Shoal Lake #40 First Nation on the other end of the aqueduct, that is only the beginning.

Winnipeg’s decision to build an aqueduct had serious repercussions for Shoal Lake #40 First Nation. Not only was the Ojibwa community dispossessed of land that included ancestral burial grounds as well as their village at the mouth of the Falcon River, they were forced to move to an adjacent peninsula. That same peninsula was subsequently severed from the mainland by a canal diverting coloured Falcon River water away from Winnipeg’s intake.

The community has struggled with its man-made isolation ever since.

It is now 100 years since Shoal Lake #40 became a captive island community within their own territory. The community acknowledged the occasion by inviting their friends and supporters to be with them for a day when they might have a chance to explain their story to the world. Maude and Mark of the Council of Canadians Ottawa office were invited but couldn’t make it. So I said I’d go. About two hours east of Winnipeg the adventure began…

It was a remarkable day, in the true sense of the word. It’s a whole different world there, only 30 km south of the Trans-Canada highway. Turning off there’s a fine paved road at first. Then not. A few kilometers in, black top gives way to gravel, and then to full suspension-wrecker for the next 25 clicks, winding through bush, past rez homes, open grassy areas, trees, a lake. It’s lush and green this time of year.

The road comes to an abrupt end at the edge of the lake. There’s a railed barge, a tiny ferry with a required two-person crew that takes four cars at a time on a 5-minute ride across the bay from Shoal Lake 39 FN–who has a road–to Shoal Lake 40 FN–who doesn’t have a road, except in winter, when deep cold lets community members get to the Trans-Canada over packed snow through what looks like a quad trail in the bush. There is a bridge on the winter road. It spans Winnipeg’s 1914 diversion canal that cuts them off from the mainland. The bridge connects two portions of winter road, but the rest of the year it goes to nowhere, and community members have to take the barge or boat across the bay to come and go between home and everywhere else.

Map by Ken Harasym

So, a road through the bush in winter, boat across the bay in summer. That leaves spring and fall. One woman told of how she once maneuvered her canoe across the bay during breakup, one foot in the canoe, one pushing forward on the rotting ice to pick up family members stranded on the other side with their groceries, trying to come home. She got them home. That time. Her story was one of a dozen or more told by Shoal Lake members during a sharing circle at the event. Many detailed the harrowing experience of falling through lake ice into black water below. Multiple times. It boggles the mind. With few exceptions, the speakers were tearful, expressing a deep and abiding frustration at seeing appeal after appeal for relief from their isolation fall on deaf ears.

There is endless irony, of course. A 1914 letter–on display in the media room at the event–from the government in Ottawa to the Kenora Indian Agent reads, in part:

“…the Greater Winnipeg Water District has made application for two portions of Indian reserve No.40 … and have also applied for Indian Bay including the islands therein…”

The letter concludes,

“The Corporation of the city of Winnipeg has the power to expropriate the lands required, but you may assure the Indians that their rights will be safeguarded by the Department.”

So, Winnipeg got their water. According to band chief Erwin Redsky, Shoal Lake got almost nothing for the loss of their “best land,” nothing for the water, and certainly nothing to correct their artificial isolation.

An agreement in 1989 did promise Shoal Lake #40 an annual income of the interest from a $6 million trust fund and “every effort” on part of both Winnipeg and Manitoba to provide alternate jobs and economic opportunities to replace the normal cottage and tourism economy available to a community on a beautiful lake 2 hours from Winnipeg. In the 25 years since the agreement, however, not one full-time job or any viable economic opportunities have been offered–largely because of the lack of secure access to the community. Both Winnipeg and Manitoba are in full support of secure access, however Canada has thus far refused to correct the problem they created when they expropriated land and gave it to Winnipeg 100 years ago.

On top of that, infrastructure costs are so high–because of Winnipeg’s water diversion canal–that the people of Shoal Lake #40 are now in their 18th year of a boil water advisory, and still awaiting funding for a basic water treatment plant.

As irony goes, it gets even better. The Canadian Museum for Human Rights, situated in Winnipeg, apparently has a feature display involving pools of “healing” water as a way to encourage visitors to “reflect on human rights.” Whose water are they using? Yup. The richness of the farce–can we use the word shallow in here somewhere?–is not lost on the Shoal Lake FN community, who used the occasion of 100 years of enforced isolation to remind CMHR staff present at the event of their mandate to educate the public about human rights issues, including those so very close to home.

Canadian Museum for Human Rights, The Forks, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada (Photo: boblinsdell on flickr. Some Rights Reserved)

“Has the power.” Many of us on the Winnipeg end of the aqueduct still miss seeing the foundations of colonialism in this story. Those words in that letter of 1914, vested by colonial laws made by arrogant colonial governments, enacted to this day in colonial courts, presume to speak for peoples that Canada has starved, dispossessed, hounded, lied to, and stolen from. Harsh charges, true. Can we face our culpability?

One last story from the sharing circle. An elder related how in 2007 he walked with his 10-year-old grandson and other members of his family and community from Shoal Lake to Winnipeg to meet with CMHR organizers to talk about their plight. He told his grandson, “If we walk, they will listen.” He said the boy’s eyes were wide with hope, certain that if people only understood the truth, some of the injustices would be amended. Well, we know how that went. The Federal government, having promised a water treatment plant, has reneged, saying that lack of access to the community would make it too costly. Last word on an all season road from the community to Highway 1? Asked for 1/3 funding, Federal Minister Bernard Valcourt wrote in January 2014: “A formal funding commitment is not achievable at this time.”

That 10-year-old boy is 17 now. A tall, quiet, handsome young man, he recently told his grandfather, “Grandpa, we walked for nothing.”

What’s so remarkable about all this? When I finally arrived at the Shoal Lake 40 community centre for the gathering marking 100 years of living on a man-made island, 100 years of ‘living on the wrong end of the pipe’ as someone said, it was a perfect summer day. Laughter rippled through the open air under the big round tent as guests arrived. We were welcomed with warmth and graciousness. The host community kids played nearby, crawling into and out of a lap as they needed to. Youth worked as ambassadors, taxied guests to and fro in fishing boats, provided information and directions, served food, loaded and unloaded tables and chairs. The women cooked two meals (Oh the fry bread and walleye!) for 100 people. There was a pervasive air of kindness and respect between community members, a kind of unspoken understanding about the essential nature of relationship, extended on this occasion to those of us who live, at their expense, in comfort and prosperity.

It’s remarkable that the people of Shoal lake even bothered to speak to us, let alone continue to provide us access to their water after enduring a century of isolation, exclusion and loss.

Linda is a settler using Shoal Lake #40 water in Winnipeg.

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.