“It is too long until the year is over because we would very much like to return to our country, because we are unable to stay here forever, yes indeed, it is impossible!”

In October 1880, when Abraham, a 35-year-old Christian Inuk from Hebron, Labrador, wrote these words, he had been in Germany for less than one month. His decision to travel to Europe had been most difficult. First, because the Moravian missionaries were totally opposed to the idea of seeing baptized Inuit displayed like animals in front of European crowds. Second, because he would be leaving his mother behind. But, Johan Adrian Jacobsen, a 27-year-old Norwegian hired by German menagerie owner Carl Hagenbeck, had arrived at a time when Abraham and his family were suffering from great poverty. Abraham therefore saw Jacobsen’s offer to earn money in exchange for demonstrating his way of life to the public, as a sign from God that this was the path away from misery. The opportunities to see Europe’s splendours, to meet with Moravian missionaries he had befriended in Labrador, and to visit Herrnhut, the center of the Moravian church, were also strong incentives. So, when Jacobsen promised to supply Abraham’s mother with all the provisions she would need until his return, Abraham let himself be convinced to embark on the voyage.

Hebron, on Labrador’s north coast. (Photo by France Rivet)

Abraham was accompanied by his wife Ulrike, 24, and their two daughters Sara, 3, and Maria, 9 months. A young single man from Hebron, Tobias, 20, also decided to join them. Finally, as Jacobsen’s interpreter, during a trip to Nachvak fjord, Abraham convinced a traditional Inuit family of three: Tigianniak, a 45-year-old shaman, his wife Paingu, 50, and their daughter Nuggasak, 15.

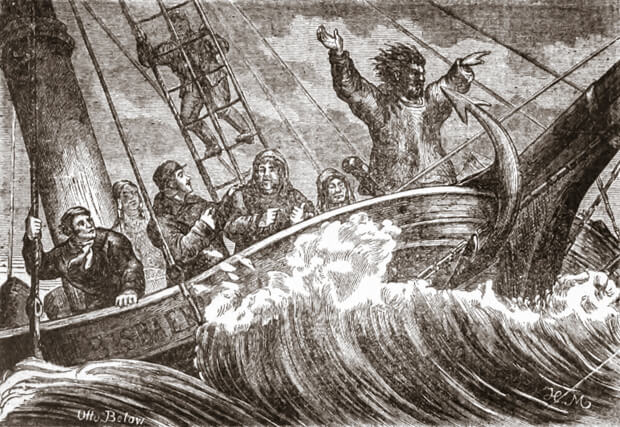

Tigianniak crossing of the Atlantic. Illustration by Hoffmann

The group departed for Europe on August 26, 1880. The crossing of the Atlantic was most challenging for the Inuit as they all greatly suffered from sea sickness, and as Abraham reported, they had lost hope of ever seeing land again. But, on September 24, the Eisbär with the Inuit, their dogs, their kayaks, their fishing and hunting gear, and their personal belongings safely arrived at its destination: Hamburg. The group was immediately taken to Carl Hagenbeck’s residence. For the next two weeks, his backyard, home to his menagerie, was buzzing with activity as visitors came to see the exotic animals, and the Eskimos.

On Friday, October 15, 1880, the group boarded the train for the overnight trip to Berlin. It did not take long for the crowds and the constant noise to start bothering the Inuit.

The very first sentence of Abraham’s diary reads,

In Berlin, it is not really nice since it is impossible because of people and trees, indeed, because so many children come. The air is constantly buzzing from the sound of the walking and driving; our enclosure is filled up immediately.

Abraham also quickly realized that coming to Europe was a mistake:

In different kinds of ways we have been lured, but even all this I didn’t recognize… It became clear to us how well we were taken care of in our country, yes indeed, long and great are the blessings we receive… We often suffer from colds, too, are often sick in Berlin, and are very homesick. We miss our land, our relatives, and our church. Yes indeed, we had to learn from our mistakes.

Labrador Inuit in front of a hut – illustration published in Prague’s Svetozor weekly newspaper, 1880.

The Inuit were exhibited at the Berlin zoo for one month. Their tour then took them to Prague, Frankfurt, and Darmstadt where, on December 14, tragedy struck: the young Nuggasak suddenly died.

Johan Adrian Jacobsen noted in his diary,

At 8 o’clock in the morning we awoke to the shout “Nuggasak is dead!” You may well imagine our shock. The physician diagnosed a rapid stomach ulcer as having caused the death. The poor parents did not stop crying from morning until evening. Of course it also had a very depressing effect on the others and on us as well.

The group moved on to Krefeld, near the Belgian border, where they were exhibited at the Bockum Zoo. It is here that they celebrated their last Christmas. In the evening of December 25, Paingu suddenly fell ill with the same symptoms as Nuggasak. For the next two days, doctors came and reassured the group that there was no need to worry: Paingu was suffering from rheumatism. Unfortunately, at 7 p.m. on December 27, ten minutes after the doctor had left, Paingu died. She was buried in the Krefeld cemetery the next day.

“The husband [Tigianniak] is very sad, of course, and expressed his wish to be able to accompany his wife and daughter soon”, reported Jacobsen.

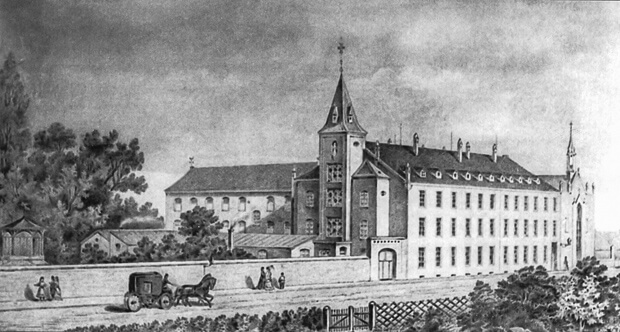

Alexianer Hospital in Krefeld, 1883. (Courtesy of Alexianer Hospital)

Two days later, 3-year-old Sara became ill. For the first time, doctors recognized the signs of smallpox. The child’s admission to the hospital was most urgent. Jacobsen fought with Abraham and Ulrike who did not want to part from their child, but, in the end Abraham accompanied his daughter to the hospital. He described the sad events as follows:

[…] little Sara stopped living, peacefully, with a great rash and swellings […] After two days of being sick, she died in Krefeld. While she was still alive, she was brought to the hospital, where I went with her. She still had her mind, while I was there. She prayed with the song Ich bin ein kleines kindelein (I am a little child, you see). When I wanted to leave, she sent her greetings to her mother and little sister. When I left her, she slept; from then on, she did not wake up anymore. For this we both had reason to be thankful. While she was still alive we went to Paris and travelled the whole day and the whole night through.

The five surviving Inuit arrived in Paris on December 31, 1880. As requested by the authorities, they were vaccinated upon their arrival. They were exhibited from January 1 to 6 at the Jardin d’acclimatation, in the Bois de Boulogne, and for a few days, they dared think the worst was behind them.

On January 8, 1881, Abraham wrote his very last letter to his friend, Brother Elsner.

Our superior does buy a lot of medicine, no doubt, but all this still does not help; but I trust in God that He will hear my prayers and will collect all my tears, every day. I do not long for earthly possessions, but this is what I long for: to see my relatives again, who are over there, […] My dear teacher Elsner, pray for us to the Lord that the evil sickness, will stop if it is His will; but may God’s will be fulfilled. I am a poor man who’s dust.

The next morning, Abraham, Ulrike, Maria, Tobias, and Tigianniak were admitted to St-Louis Hospital in Paris where, from January 10 to January 16, 1881 they died, one after the other.

Jacobsen, who had been admitted to the hospital alongside the Inuit, because of intermittent fever, wrote in his diary:

Ulrike died this morning at 2 o’clock – the last of the eight – horrible. Should I be indirectly responsible for their death? Did I just have to lead these poor honest people from their home to find their graves here on foreign soil? Oh, how everything became so totally different than I had thought. Everything went so well in the beginning. We had only now gotten to know each other and begun to hold each other dear.

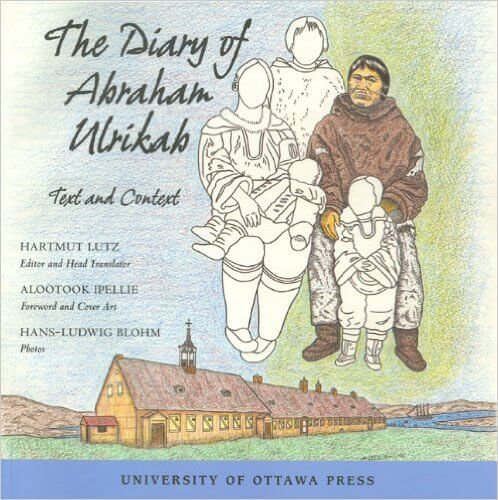

Cover of “The Diary of Abraham Ulrikab: Text and Context” by Hartmut Lutz

Following the Inuit’s death, some of their belongings, including Abraham’s diary, and the money they had earned for their work in Europe, were returned to Hebron, Labrador. There, Moravian missionary Kretschmer translated Abraham’s diary to German. A copy of his translation was discovered in 1980 by Canadian ethnologist James Garth Taylor, who brought it to the attention of the 20th century public. Twenty-five years later, in 2005, German Professor Hartmut Lutz–assisted by his students–produced a new English translation and further researched the story. Their work was published in the book, The Diary of Abraham Ulrikab: Text and Context.

In summer 2009, as I was traveling on a cruise ship along the Labrador Coast, I met master photographer Hans-Ludwig Blohm who introduced me to Abraham’s story. I had never heard of ordinary people being exhibited in zoos just because they came from faraway lands. I was shocked, fascinated, and moved by Abraham’s words. But, the story was incomplete. The book was silent on what happened in Paris after the Inuit’s death. Where had they been buried? What happened to their remains?

On board the ship, Hans and I met Zipporah Nochasak, a Labrador Inuk who’s family originates from Hebron and wears the same name as Nuggasak, the first of the Inuit to have died in Europe. Zipporah had just discovered Abraham’s story and was still very much upset. My mother tongue being French, I promised Hans and Zipporah that I would investigate whenever time allowed.

About a year into my research, I uncovered documents about anthropologists in Paris having studied Paingu’s skullcap, as well as the plaster casts of the brains of Abraham, Ulrike, and Tobias. I immediately emailed museums in Paris to inquire if they had such items in their collections. The next morning, a reply arrived from Mr. Philippe Mennecier, of the Muséum national d’Histoire Naturelle:

Mrs. Rivet we have the regret to inform you that we do not have the brain casts, but we do have the skullcap as well as… the fully-mounted skeletons of the five Labrador Inuit who died in Paris in January 1881.

Mr. Mennecier’s email also explained where the Inuit had been buried, and how their remains made their way into the museum’s collection. I was speechless. The possibility that the Inuit’s remains would still be in Paris had never crossed my mind. As I tried to figure out the implications of such an announcement, I remembered how the Inuit longed to return to Labrador. The Museum’s email was opening a door to having their wish come true.

Abraham and Tobias in their kayaks – illustration published in Prague’s Svetozor weekly newspaper, 1880.

Within a few weeks, I was sitting in Mr. Mennecier’s office. He explained that the museum would not dispute a request for repatriation as the remains have an identity. That said, such a request must be funneled through our two countries’ diplomatic channels, and be initiated by either descendants, or the Inuit’s community of origin. Since life had decided that I was the one to be told about the Inuit remains still being in Paris, I felt that it was my responsibility, my mission, to do everything I could to bring them back.

I informed the Nunatsiavut government (the self-government of the Labrador Inuit), as well as the diplomatic authorities in Ottawa, Paris and Berlin. The Nunatsiavut government confirmed that something had to be done, but before they could put the wheels in motion, it was mandatory for them to get a comprehensive picture of the past events.

Over the next three years (2011-2013), I traveled to Europe to gather as many 19th century documents and photographs as possible. I also searched for artifacts associated with Abraham and his group, and for the remains of the three Inuit who had died in Germany.

Along the way, film producer Roch Brunette (Pix3 Films), heard about Abraham’s story and my research through a local newspaper article published in the Ottawa-Gatineau area. Intrigued, he called me up. A year later, he had gathered the support of Canadian TV broadcasters as well as the required financing to start filming a documentary, Trapped in a Human Zoo.

The filming started in September 2014, as I headed to Nain, Labrador’s northernmost community, to present the results of my 3-year investigation to the Nunatsiavut government, and to Nain’s elders committee. The elders listened very carefully, asked several questions, and reached a consensus: the remains must be brought back home. This visit to Nain also served as the public announcement of the finding of the remains.

Nain Elder Johannes Lampe (left) speaking with The scientific head of the Anthropological Collections of the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, Dr. Alain Froment. (Photo by France Rivet)

The filming of the documentary provided the opportunity for Johannes Lampe, Nain’s chief elder and Nunatsiavut’s former Minister of culture, to retrace Abraham’s footsteps in Europe.

Johannes Lampe and Hartmut Lutz at the Museum of Ethnology, Hamburg. (Photo by France Rivet)

For two weeks, in fall 2014, Johannes immersed himself in Abraham’s story. He navigated on the Elbe River to get a feel for what the Inuit first saw when they landed in Europe (coincidentally, he did so on the exact same date that the Inuit sailed into the Elbe River 134 years earlier); he walked around the zoos where they showed their way of life to the European crowds; he met with the descendants of Johan Adrian Jacobsen, and Carl Hagenbeck, the two men who recruited and orchestrated the Inuit’s exhibition; he talked with Professor Hartmut Lutz, the translator of Abraham and Jacobsen’s diaries; he visited archives and saw original documents in which the Inuit’s names had been written; he held artifacts that represent tangible proofs of the Labrador Inuit’s presence in Europe; and, Johannes felt the homesickness that affected his countrymen in 1880.

The most moving and disturbing moment of the trip was undoubtedly seeing the human remains which are preserved in the museum’s reserves among a collection of 18,000 skulls and 2,000 skeletons. As the curators explained, this collection was mainly built in the late 19th century, at a time when anthropologists were aiming to sample all of mankind, to study human diversity. Nowadays, this collection is accessible only to researchers upon justification. That said, the 200 or so remains which have an identity are off limit to any study. We were granted permission to see the Labrador Inuit remains as our visit was in the context of an eventual repatriation request.

All parties involved have demonstrated that they want to continue collaborating towards the remains being returned home. Even Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper and French president François Hollande gave their blessing when, on June 14, 2013, they signed the Canada-France Enhanced Cooperation Agenda in which we find the following commitment to: “Work with the appropriate authorities to help to repatriate Inuit bones from French museum collections to Canada.”

For Johannes, seeing the remains convinced him of the necessity to bring them home:

We feel Abraham and his family wanted to come back home to their homeland. That is a wish that has to be granted. Most certainly we, as the descendants of our ancestors, have a responsibility to do what our ancestors have asked. […] I have come here to be a representative of the Labrador Inuit of today, to see the Labrador Inuit of yesterday, the human remains, and so I have seen with my own eyes, and I have felt what it is that Labrador Inuit feel. Very sad, and at the same time, I am happy that Labrador Inuit will now know that the remains of Abraham, and his family, are in Paris, and that we have something to work on.

The Nunatsiavut government is currently in the process of defining its policy on the repatriation of human remains and burial objects from archaeological sites. Public consultations were held in June 2015. The results of these consultations will be made public in the fall 2015 before being taken to the Nunatsiavut Executive Council for final review and approval. This step must be completed before the official request for repatriation is forwarded to the federal government.

The Nunatsiavut government is also trying to identify living descendants of Abraham’s and Tigianniak’s families. If any descendants are identified, they will be invited to discuss the next steps in the repatriation process.

As Johannes explained, through the mysterious appearance of a butterfly in the library of the Museum of Ethnology in Hamburg, even the spirits found a way to tell us that they are delighted with the actions currently being taken in this world. It should be just a matter of time before the spirits can be set free, before the remains come home, before the Labrador Inuit community can finally close the loop on this tragic story, and hopefully, before little Sara is reunited with her family.

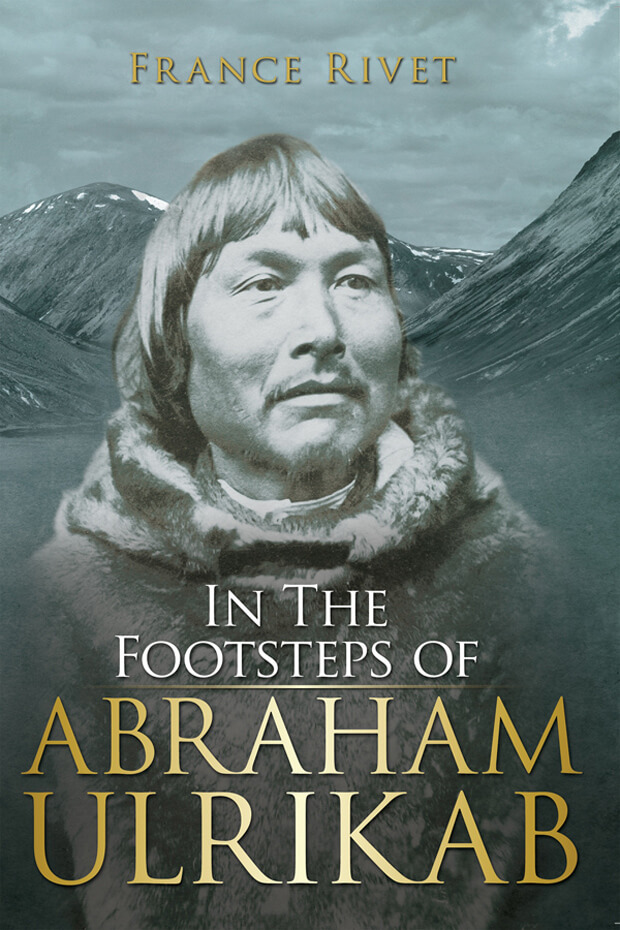

France Rivet is the author of In the Footsteps of Abraham Ulrikab: The Events of 1880-1881. She is also the founder of Polar Horizons, an enterprise that promotes greater awareness and appreciation of the Arctic, its nature, people, and history.

France Rivet is the author of In the Footsteps of Abraham Ulrikab: The Events of 1880-1881. She is also the founder of Polar Horizons, an enterprise that promotes greater awareness and appreciation of the Arctic, its nature, people, and history.

For more information: www.abrahamulrikab.com / france@polarhorizons.com

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.