“If there is not a restructuring, there will be a self-restructuring because we will not give up our land to invading settlers. If the blood of our people is spilled, we will get them out.”

This phrase from an indigenous Mískito, originally from Prinzapolka in the autonomous region of the Northern Caribbean, listed in the group of community members that have raised a defense of their lands; declares not only the clear determination to expulse the settlers who for years have occupied their communal lands, but is also the declaration of a political demand for self-determination that is not manifested publicly before the means of communication but which is read between the lines under the institutional political arena of the State.

The political demand of which he spoke has to do with the capacity for self-regulation of the processes inherent to restructuring their lands in a communal way, based, among other juridical and technical resources, on the tactical and operative control of their own armed forces to carry out this self-restructuring. This does not mean that said popular regulatory process is not exempt of risks, in large part due to the limited logistical professionalism of their armed forces, but their knowledge of the context combined with the lengthy experience of their community members with the care and vigilance of their lands and the links of trust that are woven between their communities to delegate these missions between their members, are enough to reaffirm that these communities are sufficiently organized – at least in this environment – to acquire juridical and logistical competencies at least in terms of safety.

The expression of the indigenous community member from Prinzapolka, declares, in a furtive and hidden manner as mentioned in the above paragraphs, a decentralizing political demand that is contained within the infrapolitics of the communities of Moskitia. This is to say, within the undeclared, but latent, politics of the communities of Moskitia. As Jorge Yagüe exposes well, “it is thus a policy of no-power, a policy against policy, a policy of no policy…It is the action that, searching for an impact on power relations, a, well, political impact, suspends in it all that could reproduce those relationships.” Following the book of James C. Scott, Domination and the Arts of Resistance, “the term infrapolitics appears to be an economic way to express the idea that we find ourselves in an environment of discreet political conflict. … the deaf struggle that the subordinate groups wage daily is found – like infrared lights – past the spectrum of the visible. Its invisibility is, as we have already seen, results a good deal from a deliberate action of a tactical decision that is conscious of the balance of power.”

On the other hand, the declarations of Lottie Cunningham, the president of the Centro por la Justicia y Derechos Humanos de la Costa Atlántica de Nicaragua (Center for Justice and Human Rights of the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua), powerfully call my attention as she, before a paternalistic State discourse that, paradoxically, delegates a conciliatory role to and dialogues with the national army, recently declared to a national newspaper a phrase that puts in perspective the necessity to divide the supposed conciliatory role from the police institution and the national military from the unrestricted self-determination process of the communities of Moskitia.

“We see the State as unique. But we know that the institutions that provide its security are the police and the military. That is my concern, what dialogue?…for us the community has self-determination.”

In stating this affirmation, Cunningham not only tells state hegemony that the military cannot – even through a logical instrument – be an institution with the capacity to dialogue and that the process of self-determination, as it literally reads, does not belong to anyone but the communities of Moskitia, but also manifests in a low tone, tenuous but overwhelming, that politically the resolution from which the conflict spills, is a task that can be carried out by the community members themselves if the non-existent conditions such as the logistic security of immersion, the tactical protection of human lives, the common weapons, and the juridical resources of the restructuring were in the hands of communal authorities; the problem probably would have been resolved a while ago without the hand of a coercive institution like the national army.

Instead, lets analyze, how much time has passed since these communities demanded that the State fulfill precautionary measures? How many disappeared and murdered indigenous people has this institutional negligence cost since the conflict sharpened in the year 2015? Have the improvised, institutional restructuring commissions delegated by the State achieved something concrete in almost two years of conflict?

With this I do not want to overstate this, but instead criticize the exclusionary history of how these national civil-legal security institutions have marginalized a region so it has to resolve amongst itself its own conflicts – even though their conflict resolution norms and traditions and ancestral judicial processes subsist indistinctly – instead I want to clarify how the empowerment of the community members through their own unofficial methods of territorial resistance, their justice proxy and logistical methods to resolve conflicts require institutional competencies to achieve these objectives without the need to depend on centralized institutions of judicial public control.

These competencies, logically first require to be requested by the autonomous cases of the regional government, but, as I showed at the beginning, the same structural conditions that do not allow for a communal and regional leadership to be reached that achieves the sufficient articulation to openly declare before national and international opinion, that they need said competencies and attributes to strengthen their own administrative and judicial communal organisms, which also strengthen the institutional channels to enforce regional autonomy.

As I stated at the beginning of this article, if I have not openly stated the need to transfer judicial and technical competencies to create a political apparatus in the community of Moskitia, it has been, among other reasons, due to the lack of political will of the State and the same regional autonomous governments that, lamentably, are contingent on the political alignments of the groups with political power nationally. Nevertheless, this demand, although it lies circumspect in the declaration of the indigenous before the means of communication, is not only a discursive elaboration that is latent and hidden in the communal language, but a real necessity that should be adapted to the true structural conditions of the region.

COMMUNITY POLICE IN MOSKITIA: FUNDAMENTAL DECENTRALIZATION

The experiences of Community Police in diverse latitudes of the Latin American continent where indigenous groups prevail, have had promising results regarding traditional forms of administration and delivery of justice, and above all with administrative systems of protection, control, and civil security. Such is the case of the Zapatista communities in Chiapas, Mexico, in Cheran, Michoacan, and indigenous communities in the state of Guerrerro, Mexico.

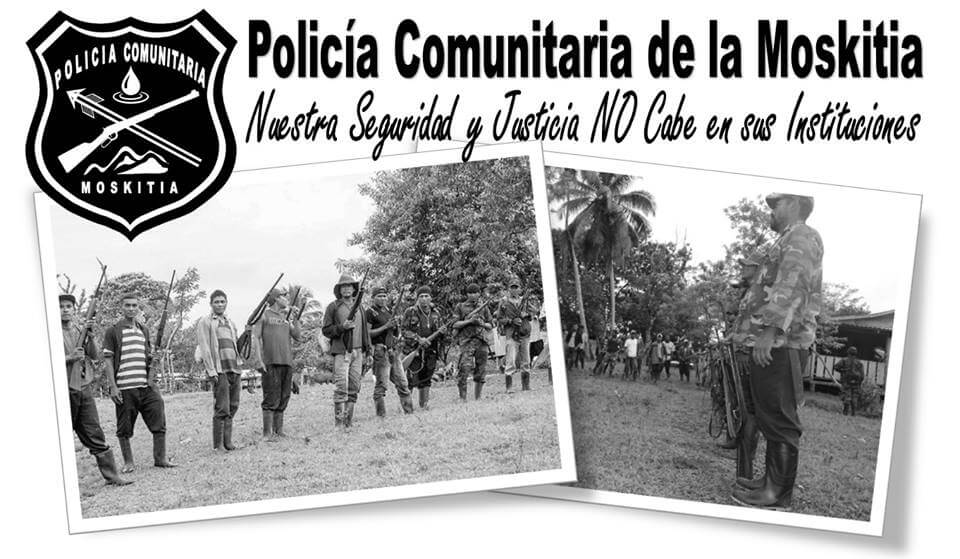

Nonetheless, even though the institutions of some community leaders regarding the consolidation of a decentralized political body are nebulous, the practices of community policing, generally sustained with the operative logic of the militia vestiges of MISURASATA and other indigenous military organizations that grew during the decade of the 80s, have fomented, but not consolidated, a rural military corps with a rudimentary arms arsenal to confront the settlers invading their communal lands.

This communal, proto-police organization is a clear example of a possible structure for a community police that could facilitate the constitution of a decentralized police model in Moskitia.

Regardless, what has impeded the transfer of juridical attributes and technical competencies for the formation of an autonomous institution under civil control?

Covenant 169, ratified in Nicaragua in the year 2010, clearly says in Article 6, section C, “establish the means for a clear development of the institutions and initiatives of the people, and in the appropriate cases to provide the necessary resources for this end.”

The experience of the Community Police of Costa Chica and Montaña de Guerrerro in Mexico is an institution that is born, among other reasons, in 1995 at the roots of insecurity on the paths that connect the indigenous communities, above all the latent racism in the national security and justice institutions that abused their institutional power to discriminate against and violate the human rights of the indigenous populations in the region. With a census population of more than 300,000 inhabitants, the Community Police of Guerrero managed to lower the region’s crime rate by 95%, employing their own model of civic control and public security and a system for the administration of justice connected to their traditional ways of imparting justice called the Sistema de Seguridad y Justicia Comunitaria (Community Security and Justice System).

The example from this region, even though it is far away in many ways from the reality of Moskitia, coincides in many aspects, above all, in relation to the theme of the defense of collective rights of indigenous peoples, now that, similar to the communities of Moskitia, the corruption of the security and justice institutions of the state and federal government favor groups with economic power, such as large land owners and politicians that illegally appropriate the communal lands inhabited by indigenous families.

Outside of the particularity of the Community Police of Guerrero, my intention is to demonstrate, grosso modo, how through the experience of these community models of security and justice, the self-determination of the indigenous peoples strengthens the community’s ties and strengthens, undoubtedly, autonomy. It is for this reason, and not other, that the primary demand for the decentralization of the justice system in Moskitia could open the path to the founding of a decentralized Community Police connected to the sociocultural reality of Moskitia.

The founding of an autonomous, decentralized, and communitarian justice system could take a lot of time, however, the demand for the decentralization of the security system, such as the National Police, could start the decentralization of a penal system in accordance with the traditional forms of justice in the communities of Moskitia.

In the case of Guerrero in Mexico, they initially appealed for the creation of a Community Police, but soon after it was consolidated in its totality and integrated into the Sistema de Seguridad y Justicia Comunitaria (Community Security and Justice System). This triumph not only demonstrated the operative potential of the indigenous communities in regards to the decentralization of the judicial-security apparatus of the Guerrero zone, its army and systematic consolidation of this, but also strengthened regional autonomy.

These practices, reaffirmed by community ties and civil solidarity, demonstrate that the cultural foundations and the intercultural army of the Na’Savi and Me’Pháá indigenous peoples of Costa Chica and Montaña de Guerrero, were able to consolidate autonomous jurisdiction, even lacking the technical competencies of the State. To date, the Coordinadora Regional de Autoridades Comunitaria – Policía Comunitaria (Regional Coordinator of Community Authorities – Community Police), has expressed the following written communiqué, a tenacious sign of the revaluation of their right to self-determination: “we reject whatever intent the government makes to make us official, we will never subordinate ourselves to the State”.

In any of these cases, the public declarations of some of the indigenous Mískitos and Mayagnas of Moskitia before the public press have manifested an increasing inconformity in the past few years with respect to the State mechanisms for conflict resolution in the region. There exists a structural disenchantment with national police and military authority and the national justice system lacks credibility.

The constant denouncements against the security and justice system that, due to omission or complicity with the central government, fall into a myopia before the collective human rights of the people of Moskitia, above all in the Northern Caribbean where many indigenous people have been displaced from their communities and had to seek refuge on the border with Honduras due to threats from settlers, who, in many cases carry high-caliber arms and are protected by elements from the army, like in the case of the logging mafias which feeds the relationship of illegal logging that is confiscated by the Batallón Ecológico (Ecological Batallion) – an appendix of the National Army – that traffics the seized wood through the Instituto Nacional Forestal (National forest Institute) so it can be usurped by the parastatal group ALBA-Forestal.

As I explained to great lengths in a recent article: the warnings of the indigenous peoples to the State to comply in record time with the restructuring and expulsion of the settlers, no need to read this literally (but between the lines) as a threat against the central government or against the settlers, but against the centralization of the possible structures that silence them – and oblige a mumble before public opinion – the enunciation of the true mechanisms to consummate self-determination.

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.