At this time of year the weather changes quickly in the north of the Colombian province of Cauca. A sudden chill can arrive on any breeze, sending shivers through the streets and sugarcane fields alike. Intense but short-lived bursts of rain usually follow. And the sun offers little consolation, returning just long enough to see the surrounding mountains bested by cloud.

The prospects for peace and regeneration in Colombia are as variable as the weather. Right now proposals are being developed to transform the agriculture-driven narcotics economy into one that produces medical marijuana and coca tea. The valley that runs down from mountainous Toribio, long contested by the FARC and army, has been touted as a future venue for mountain-biking.

But the stretch of land that runs where the mountains meet the plains, between the towns of Corinto, Caloto, and Santander de Quilichao, is becoming an epicentre of violence against social leaders that is shaping Colombia in the wake of the peace process with the FARC guerrillas. A report by the Fundación Ideas para la Paz (FIP) recorded 348 acts of aggression against social leaders in 2016 including 237 threats and 71 assassinations. The three areas of Colombia most affected were Cali (35 acts of aggression in a city with a metropolitan population of 3.4 million), Barranquilla (18 acts in a population of 2.4 million), and Caloto (15 acts in a population of just 17,642).” The FIP report adds that in this wave of violence “indigenous leaders (who were subjected to 55 acts of aggression) and trades unionists (subjected to 51 such acts) have been the most affected”.

The reservation of Huellas, Caloto, where the mountains meet the plains. Photo: Robin Llewellyn

The United Nations has condemned the wave of violence and observed that “75% of the homicide victims were carrying out their activities in rural environments, and that the methods of the killings and assassination attempts show a high level of sophistication to conceal the intellectual authors.”

Responsibility for many of the attacks has been claimed, however, by paramilitary groups including the Aguilas Negras (Black Eagles), the Rastrojos, and the Urabeños; groups that developed out of the right-wing paramilitary Self-Defence Forces (AUC) following their partial demobilisation between 2003-2006.

The Medellin-based think-tank Insight Crime describes the Black Eagles as “a non-cohesive group dedicated to protecting the economic interests of former mid-level paramilitary commanders scattered across Colombia… Frequently, paramilitary successors who have continued threatening or murdering journalists, lawyers and human rights activists have done so using the Aguilas Negras name. This political bent, along with their lack of a central leadership, distinguishes them in part from the other criminal groups operating in Colombia.”

The Nasa reservation of López Adentro lies within the municipality of Caloto. Its Governor, Daniel Estrada, told IC Magazine: “We have had a peace process in Colombia but the threats continue” frequently in the form of pamphlets signed by the Black Eagles that target “Leaders of the community, indigenous guards, council members, those involved in the liberation of land…”. The liberation of land is the Nasa term for their 46 year-old attempt to resettle and reseed the rich land of the plains of Cauca from which they say they were forced at the start of the twentieth century. “In López Adentro we’re currently involved in liberating two sugar haciendas: La Albania and Vista Hermosa.”

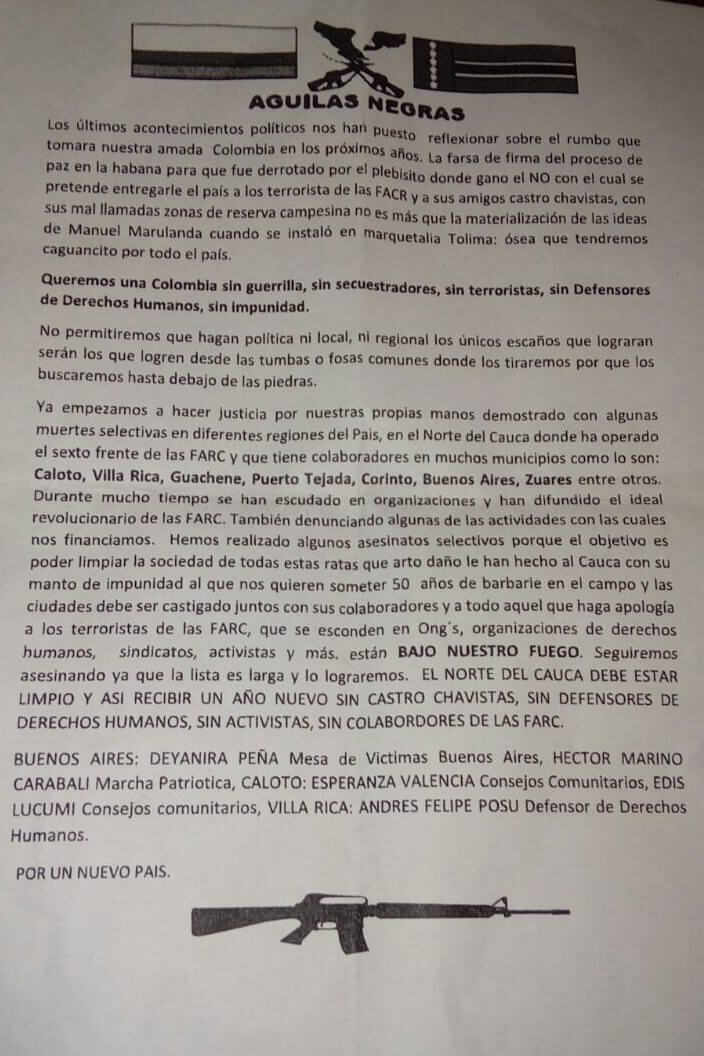

Last week new pamphlets signed by the Black Eagles were distributed in Caloto and other municipalities naming social leaders and warning them “We won’t permit them to conduct local or regional politics. The only seats they will win will be those in the tombs or in the common graves where we’ll throw them”. The pamphlet carried a claim of responsibility for “some selective assassinations” and declared the objective to be “a Colombia without guerrillas, without kidnappers, without terrorists, without defenders of human rights”.

A typical Black Eagles death threat, this time threatening predominantly Afro-Colombians. Photo: Robin Llewellyn

Daniel Estrada says that paramilitarism doesn’t reach the reservation in the form of names on pamphlets: “Here there is a group on the margin of the law that has a paramilitary structure. Its members wear both civil and military clothes, they pass at night in Troopers with black windows. On Nov. 23, ten to twelve people tried to kill a 17 year old in the La Mora sector of the reservation.”

The Association of Indigenous Councils of North Cauca (ACIN) says that fifteen of its members have been killed this year and that Cauca’s Afro-Colombian and campesino leaders have also been targeted. On Nov. 11, the campesino human rights activist and member of the left-wing Marcha Patriótica party José Antonio Velasco was killed in Huasano, Caloto, following the assassination of Caloto campesino human rights activist Jhon Jairo Rodríguez Torres. Cristian Delgado, spokesperson for the Francisco Isaías Cifuentes Human Rights Network, said the two killings had been wrongly attributed to personal circumstances or micro-trafficking because the authorities don’t want to recognize that they were acts of paramilitaries.

In the context of pervasive impunity throughout Colombia (Freedom House reports that convictions are achieved in only 10 percent of murders) the search for motives is widespread. The FIP report cautions against seeing paramilitarism as the “black hand” behind all the violence and elaborates an explanation that has significant acceptance given the spike in killings following the No vote in the plebiscite on the peace accords:

“’Peace’ continues to be a well-elaborated script that needs to be put into practice. It is still a dream and its opponents know very well that the social leaders carry the key to putting the peace accord into practice, and that one way to impede that process is to destroy the social organization that can push, demand, and monitor the implementation of the accord from the regions.”

Colombia is supposed to see land seized during the conflict–which amounts to around 15% of national territory– returned to the displaced, in a process that impacts large national and international companies.

The network of those responsible for many of the killings, suggests the FIP report, “has been much more extensive than we could imagine. Not just the state through corrupt notaries, but also local elites who continue contracting the services of organized crime to threaten and assassinate those who hinder them.”

The report’s author, Eduardo Álvarez Vanegas, told IC Magazine that, “in relation to the Black Eagles and their pamphlets and death threats, these are the typical distractionary elements used to hinder investigations and hide those directly and indirectly responsible for attacks. It is a very typical modus operandi in the production of this type of violence that is more selective and less indiscriminate.”

His report claimed that “In the case of the indigenous of Cauca that have opposed illegal mining and narco-trafficking, we can’t exclude the responsibility of narco-traffickers and organized crime”.

The road from López Adentro to Caloto passes the reservation of Toéz. There, Edwin Mauricio Capaz of the Human Rights Network of ACIN agrees that some of the local violence “is a response to the continued need felt by some to control narcotrafficking, because the money involved is immense. There are parallel industries in illegal mining and extortion, and the trafficking [of] chemicals needed for the drug trade. So there is an illegal economy based in fear and terror that an illegal armed group wants to control. The FARC is in the process of laying down its arms and has left a vacuum. There are others entering and there are micro-descendants of the FARC that are inheriting these interests.”

But Capaz cautions that, “For a long time in this zone between Caloto and Corinto the community has been seeing a pattern of armed groups that are not guerrillas and are not the Fuerza Publica (police and army) and yet are equipped with rifles. This theme of paramilitarism is very complicated in Cauca.”

“There is also a continuation of a paramilitary logic; groups that might not identify as paramilitaries but do act like paramilitaries, that protect powerful interests in this zone, such as those of large land owners… this has been evident during the struggle for the liberation of Mother Earth. There’s a dynamic here that doesn’t want to leave behind illegality.”

The road to Caloto then passes the reservation of Huellas, where 20 community members were killed while occupying the sugar hacienda of El Nilo on Dec. 16, 1991. Following the massacre, the state promised to transfer 15,600 hectares to the Nasa as compensation for a history of abuses, 141 hectares of which remain to be transferred. On Aug. 4 2014, Police General Fabio Alejandro Castañeda Mateus was ordered to pay compensation for having actively participated in the massacre as the captain of the anti-narcotics police based in Santander de Quilichao.

As Huellas passes on the left of the road, on the other side passes the hacienda of La Emperatriz, whose possession is fiercely contested by the Fuerza Publica and Nasa activists.

Nasa activists replanting the sugar plantation of La Emperatriz, Caloto, Cauca. Photo: Robin Llewellyn

In the office that the indigenous councils of the municipality maintain in the centre of Caloto, the governor of Huellas, Nelson Pacué, told IC Magazine that “There are regular threats being made against indigenous authorities and against those who cross the road to engage in the liberation of land. We also see cars with black windows passing in the night, that’s when they’re active, sometimes just one car and sometimes two.”

“On Nov. 22, the indigenous guards saw a car with black windows enter the reservation, a grey pick-up that had been seen in the place where two members of the Toéz reservation were killed. The guards intercepted the car and detained three armed men in civilian clothes; two claimed to be from the anti-narcotics police and one had no papers but appears to be an informant. They have been processed by the community and turned over to the Fiscalia (Colombia’s investigatory police) for their status to be verified and their past to be investigated.”

Police incursions into indigenous territory have to be permitted beforehand. The reservation’s official documentation of the initial encounter describes how the policemen repeatedly changed their story. First they claimed to be visiting a Pedro García (who was unknown in the area). Then they claimed to be visiting the La Emperatriz hacienda. Then they said they were lost. Finally, they claimed to be anti-narcotics police and asserted that the path of Chorrillos–where they were intercepted–was a corridor for narco-trafficking. The document notes the path of Chorillos is a cul-de-sac.

One of the policemen, on seeing a Kiwe Thigna (indigenous guard) allegedly tried to bribe their way out of the predicament, saying: “Sort this out for us or they will sack me from my job.”

The Nasa presenting the 3 captured suspects to the state. Photo: Anonymous

The policemen were identified as Jhon Berlín Gómez Ocampo and Giovanni Bautista Calderón, and the informant lacking papers as Manuel Muñoz of Santander de Quilichao, and their car a grey Dmax registration number DIN 517.

Commander Trujillo of the Fiscalia confirmed to IC that the two men were indeed part of the anti-narcotics police, and were now back at work. “They were just pursuing their intelligence-based anti-narcotics work in an area where they weren’t sure of the exact location of the border of indigenous territory and crossed over inadvertently.”

The reservation recorded a GPS system among the men’s possessions, and a member of ACIN responded: “the anti-narcotics police know the local geography extremely well.”

Whatever the nature of the mission of the anti-narcotic agents, suspicion of the Fuerza Publica is widespread among social leaders in Cauca, and the links between the state and paramilitary groups remain strong throughout Colombia. According to a leaked report from the Inspector General’s Office and correspondence between the Inspector General and Congressman Alirio Uribe, “It is clear that in some cases members of the security forces have been influenced by criminal interests”. The Congressman claimed that “The regional distribution of alleged collusion between state actors and illegal armed groups is surprisingly similar to the regional distribution of death threats and assassinations targeting human rights workers, unionists and others.”

The FIP report urgest the state to respond to the wave of killings by moving beyond its “cosmetic response” of inter-institutional committees and high-level tables of human rights, to “mount investigations that clarify the acts and those directly and indirectly responsible, including if they were involved, the untouchables that form part of the criminal spheres of the state.”

To some commentators the challenge in overcoming the latest violence remains immense, if only because it stems from the continued dominance of the “paramilitary ideology or phenomenon” in Colombia. Germán Ayala Osorio, professor at the Universidad Autónoma de Occidente, writes, “The economic, social, political and cultural project that the paramilitaries have been engaged in continues, only that now the political visibility that the AUC leaders once had is in the hands of the ‘natural’ agents and supporters of that Phenomenon, and the direct beneficiaries of the deprivation of large areas of land that the paramilitaries achieved are the agro-industrialists, sugar mills, cattle ranchers, mining companies and all those friends of the idea of the latifundia as the only possible model of production.”

Ayala Osorio also observes, “The paramilitary successors that did not demobilize are now acting without clear political references, which means that their operation is reduced, perhaps, to the provision of private security services or criminal actions. The dispersed operation of what the authorities call the “neo-paramilitaries” serves the strategy of sectors of the Establishment that insist that the paramilitary phenomenon and its armed expression, ‘Paramilitaries’, do not exist anymore.”

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.