How should indigenous forest peoples respond when the state declares them at risk of physical and cultural extinction?

How can they continue to protect their land and cultures when squeezed on all sides by armed conflict and encroaching oil companies?

To whom do they turn when they are abandoned by the very government institutions tasked with their protection?

The Siona people of the Putumayo — a watershed straddling Ecuador and Colombia — must answer these questions before their culture and the rainforest upon which it depends are lost forever.

Photo: Mateo Barriga Salazar

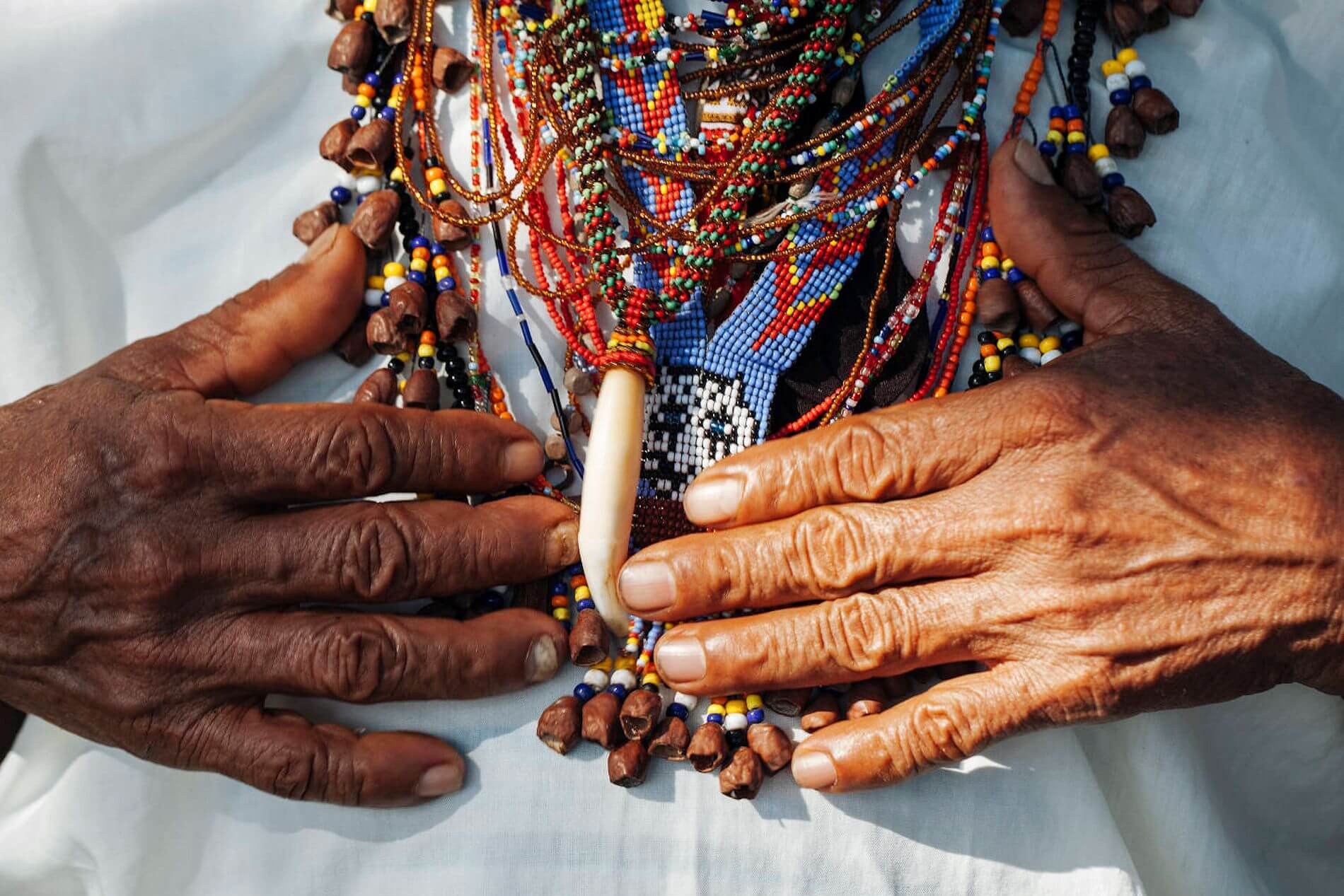

The Siona of Putumayo are a yagé drinking people. The hallucinogenic brew, also known as ayahuasca, is at the core of their ancient culture and current resistance.

It allows them to contact the spirits of the forest, heal illness, and bring the community together to make important decisions and face challenges as one. Above, elder shaman Humberto Piaguaje prepares yagé for the night’s ceremony.

Photo: Mateo Barriga Salazar

The Siona successfully guarded their yagé traditions throughout the Spanish invasion and their subsequent forced conversion into Christianity. They protected it during the slavery and brutality of the rubber trade of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and then again under a wave of Evangelical missionaries in the 1960s, which arrived intent on destroying the “devil’s brew” at the center of Siona culture.

Beginning in the 1980s, the Colombian three-sided conflict between the state, right-wing paramilitaries, and left-wing guerillas brought peril to daily life in the region. Yagé ceremonies were often interrupted by nearby gunfire or explosions.

Yet today the tradition remains strong. It is common for more than 200 community members to gather for the drinking ritual, a rarity in a region where the tradition is weakening under the accelerating encroachment of modern society.

Photo: Mateo Barriga Salazar

Whether their houses lie within the community of Buenavista on the Colombian side of the river, or in the community of San Jose de Wisuya on the Ecuadorian side, the Siona see the international border for what it really is: a river that’s long been their lifeline, since before either country existed.

For all practical purposes, the fiction of two distinct communities exists only on paper. Mario Erazo Yaiguaje, pictured above, is both the Governor of Buenavista and a member of the Leadership Council of San Jose de Wisuya.

Photo: Mateo Barriga Salazar

On both sides of the border, the Siona face recent threats from the same UK oil company, Amerisur Resources, which owns interests in high-risk oil blocks in Latin America. In Colombia, Amerisur operates dozens of oil wells within a few kilometers of Siona territory. The company proposed a large-scale oil exploration project at the heart of Siona land in 2014.

Photo: Mateo Barriga Salazar

The Siona of Putumayo have mobilized a full-fledged resistance against the environmental and culture destruction caused by oil activity. As stated in their Resolution of 2017, “We ratify that all of our territory, in its entirety, is sacred for our People, and for that reason we will not allow our territory to continue to be affected by the extractive ambitions of companies like Amerisur or the State.”

Photo: Mateo Barriga Salazar

In Ecuador, the Siona have launched a legal battle against Amerisur and the state-owned oil company PetroAmazonas for the illegal construction of a transnational pipeline beneath the Putumayo River.

The construction of the pipeline caused grave environmental and spiritual damage to the Siona, and it was built without conducting an environmental impact statement, without an approved environmental license, and most importantly, without prior consultation of the Siona, a right enshrined in international law and recognized by the Ecuadorian constitution.

Photo: Mateo Barriga Salazar

In Colombia, an Amerisur pipeline upriver from the Siona dumped toxic waste waters directly into the Putumayo for years. It was removed in 2013 only after neighboring communities filed complaints and threatened to blockade Amerisur’s operations.

The water is not safe to drink, and after bathing the Siona often get the rashes and boils that are typical of toxic exposure.

Photo: Mateo Barriga Salazar

Meanwhile, the Siona remain caught in the crossfire of the Colombian armed-conflict. Despite the recent Peace Accord, the three sides maintain strong political and economic interests in the region.

In 2009, the highest court of Colombia declared the Siona, along with 33 other indigenous peoples, at risk of physical and cultural extinction due to the armed-conflict, and required the state government to implement immediate measures to guarantee their survival. Instead, the state facilitated Amerisur’s oil operations in Putumayo and provided military personnel as round-the-clock security for the company. The increased military presence caused an escalation of armed hostilities, including shootouts, the laying of landmines and forced conscription.

For the Siona, the recent agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC is an empty political ploy. The early months of 2018 have brought an intensification of violence throughout their territory.

Photo: Mateo Barriga Salazar

Puerto Silencio, a small Siona village three hours into the forest from Buenavista, has born the brunt of the conflict.

The community lies along a tributary of the Putumayo that has for years been used as a key coca trafficking route. The primary natural material for cocaine production, coca leaf farms flourish throughout the Putumayo region, where poverty is rampant and economic alternatives are scarce. Some local farmers are forced by criminal organizations to grow the crop, threatened with violence if they don’t produce on schedule.

Photo: Mateo Barriga Salazar

Land mines placed by the FARC and Colombian military litter Siona territory. Above, Celio and Placido Yaiguaje speak at the site in Puerto Silencio where their mother was killed by a landmine. She was walking down to a favorite fishing spot near her home when a landmine placed by the FARC to deter Colombian military advancements took her life.

The presence of landmines has confined the Siona to just a few known trails, and has made traditional practices such as hunting, fishing and food recollection prohibitively high-risk.

Photo: Mateo Barriga Salazar

The Siona have persevered throughout centuries of attempts to wipe them out, and they have no intention of allowing new threats achieve what the Conquistadors and the rubber barons could not. They have legal demands pending before national and international legal systems to enact urgent measures to guarantee their physical and cultural survival.

On May 10, the Siona will appear in the Dominican Republic before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights as one of three case-studies on the vulnerability of Colombian indigenous peoples to violations of their human rights in conflict areas, with a specific focus on the heightened risk brought by the presence of extractive industry.

Photo: Mateo Barriga Salazar

Within their communities, the Siona have initiated an indigenous guardia, made up of young men and women dedicated to protecting the community’s well-being through autonomous monitoring and control of their territory.

No armed actors from any faction are allowed within Siona territory. It is the guardia’s role to inform armed-groups passing through that they must take a different route. Over the past ten years, the joint guardia of Buenavista and Wisuya has grown to over 60 members.

Photo: Mateo Barriga Salazar

The palm-wood batons carried by all members of the guardia give them strength, but the risks are real. In 2017, over 120 environmental and human rights defenders were killed in Colombia, many of them indigenous.

Siona leaders such as Celio, Alonso, Mario and Sandro, have all received death threats due to their roles defending their territory.

Photo: Mateo Barriga Salazar

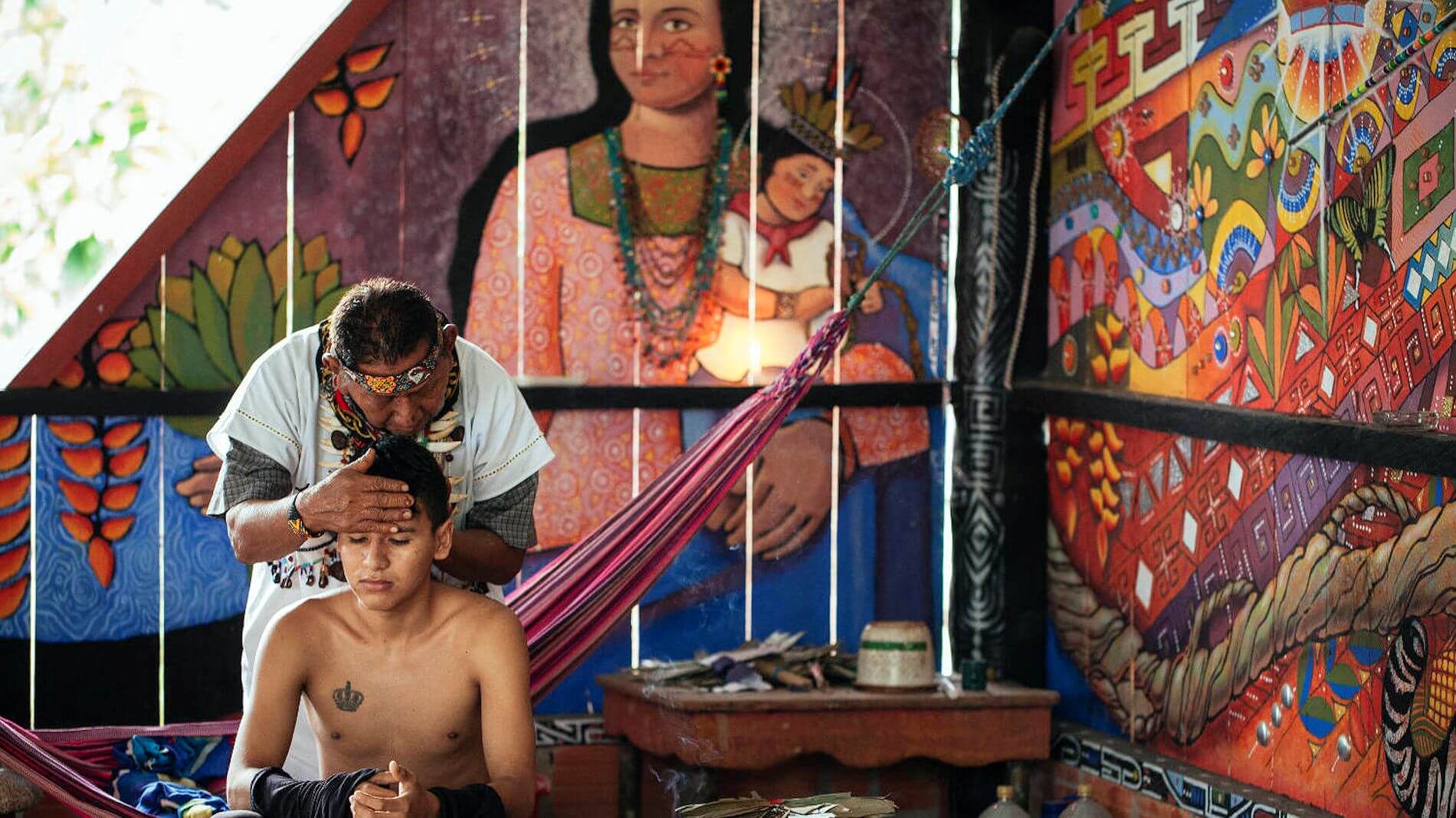

For guidance and spiritual protection, the leaders and guardia turn to the elder shamans, taitas as the Siona call them, and to yagé.

Photo: Mateo Barriga Salazar

Leaders such as Sandro Piaguaje, pictured above, are elected by the community, but only validated after a yagé ceremony and the approval of the taitas. Being a leader or a member of the guardia carries the responsibility of participating in continual yagé ceremonies to seek guidance from the spirits, collectively discuss important decisions with the taitas, and build spiritual strength for the path ahead.

Photo: Mateo Barriga Salazar

Sandro says that the taitas told him, “Get rid of that idea that this is the beginning, we began this a long time ago. For us, this isn’t war. This is survival. This is peace. This is harmony. This is understanding. This is brotherhood.”

Photo: Mateo Barriga Salazar

Over the next few months, Amazon Frontlines will be sharing more stories about the Siona of Putumayo’s battle for cultural and physical survival.

For the Siona of Putumayo, standing up in defense of their territory requires courage and it requires our solidarity. Stand with the Siona by signing and sharing our pledge.

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.