Grand Canyon, AZ — On October 13, 2016, Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (ADEQ) issued three controversial air quality permits for uranium mines near the Grand Canyon. The uranium mining will desecrate sacred sites and further contaminate communities that have already been plagued by decades of toxic abandoned uranium mines.

“Mother Earth is very precious, every living thing depends on her,” said Cameron Chapter president Milton Tso, “Uranium belongs to our mother, it belongs to her and that’s where it should stay. You’re going to have a battle, I guarantee that you’re going to have a battle from me and from everybody else if this stuff starts going towards our way.”

“We are very upset that ADEQ approved the air quality permits.” stated Havasupai council member Carletta Tilousi, “Even though we stood firm on protecting the lands and sacred areas, again the state of Arizona won’t protect our Grand Canyon homelands as they went ahead and issued the air quality permits. We are very disappointed with the agency.”

Energy Fuels Resources, Inc. (EFRI) operates three uranium mines with leases from the US Forest Service on public lands near the Grand Canyon. The EZ and Arizona 1 mines are located north of Grand Canyon National Park, while the Canyon mine is located abut 5 miles to the south. Arizona 1 mining operations have ceased though uranium is still being stored onsite and hauled to the company’s processing mill in White Mesa, Utah. Energy Fuel’s EZ and Canyon Mines are currently in process of development.

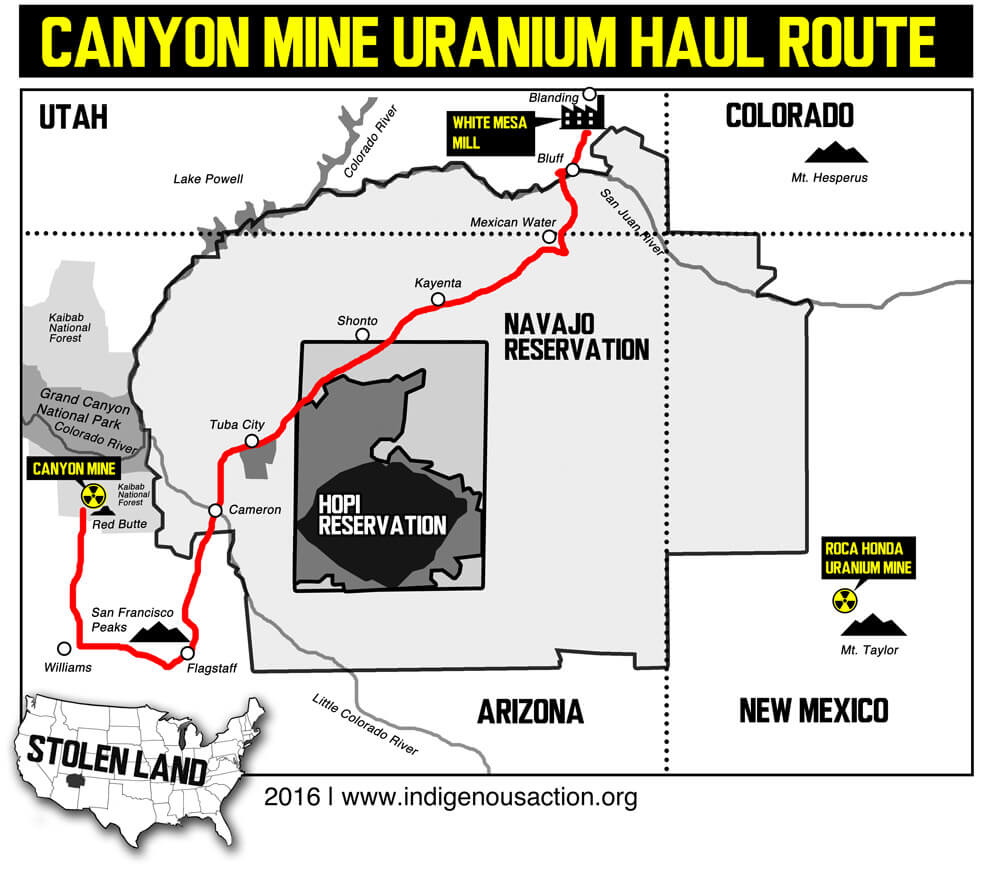

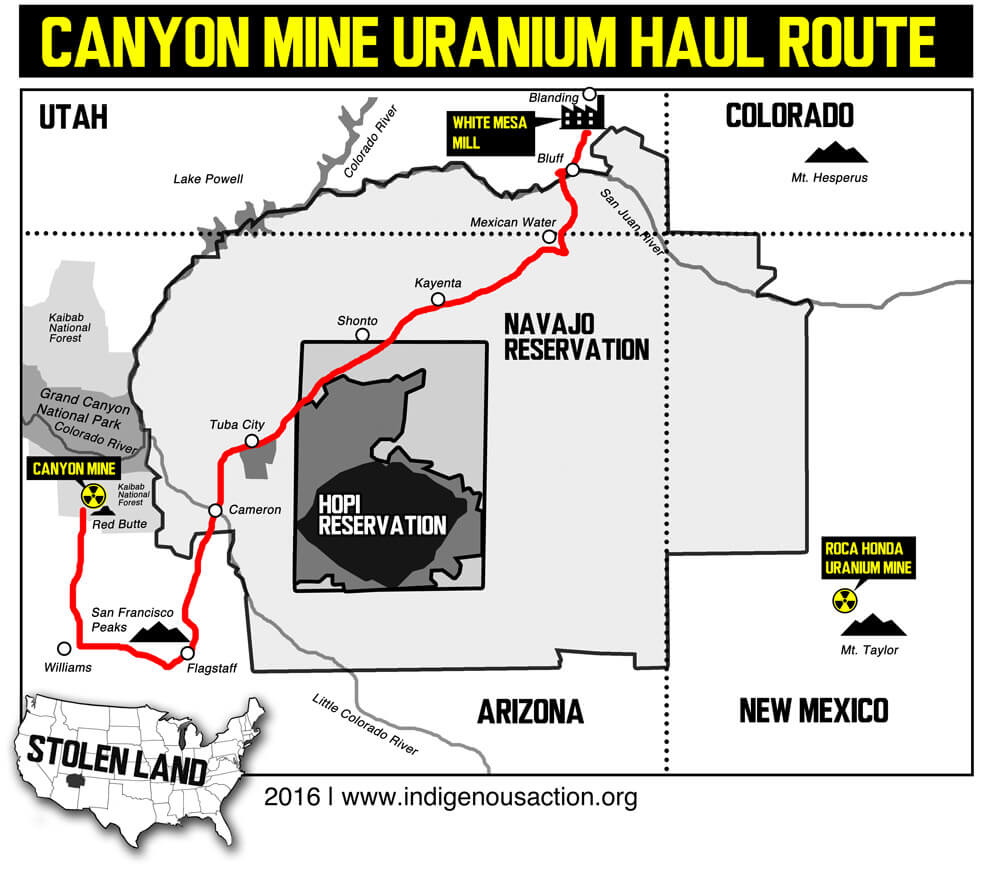

Uranium ore from Canyon Mine would be hauled in 30-ton capacity trucks up to 25 times per day, 300 miles through Flagstaff, Cameron, Tuba City, Kayenta, and Mexican Water to the company’s White Mesa Mill near Blanding, Utah.

The only protection communities along the haul route would have from radioactive pollution would be tarps covering the toxic ore.

Although the Navajo Nation has banned uranium mining and milling since 2005, nothing precludes transportation of this hazardous material through Diné lands. The 2005 ban was prompted by the hundreds of abandoned uranium mines that plague the reservation.

Areas such as the Diné community of Cameron continue to face high rates of cancer and poisoned drinking water due to uranium mines left abandoned from the nuclear industry’s toxic legacy.

According to the EPA, “Approximately 30 percent of the Navajo population does not have access to a public drinking water system and may be using unregulated water sources with uranium contamination.”

Nearly 180 miles of the Canyon Mine haul route is through the Navajo Nation, crossing bridges over the Little Colorado and the San Juan Rivers. In 1987, two separate accidents involving haul trucks spilled uranium ore across highways on the Navajo Nation.

ADEQ was initially prompted to suspend air pollution permits for the three mines due to high levels of radiation detected at one of the companies existing mines. The department recently held a series of public hearings in Northern Arizona regarding the permits.

At the August 30, 2016, hearing in Flagstaff, AZ, Milton Tso stated, “Now we’re talking about one of the most sacred places on earth that you want to mine uranium, the Grand Canyon. It’s not only sacred to us as Native people, but sacred to the whole world. We get millions of people that come just to look at this Canyon. And the water that runs through there is very sacred. There’s no guarantee for safety around uranium, around oil, around anything that’s brought out of our mother. There’s no guarantee that it’s going to be safe and it never is, there’s always going to be a spill, there’s always going to be an accident.” stated Tso.

When issuing the approval for air quality permits for the uranium mines, ADEQ responded to public concerns regarding tarps covering the radioactive ore by making requirements for tarps covering haul trucks more “stringent.” ADEQ stated that, “The tarp will be lapped over the sides of the haul truck bed at least 6 inches, and secured every 4 feet with a tie down rope.”

Red Butte

The Canyon mine where EFRI is currently drilling for uranium is near Red Butte, a mountain held sacred by the Havasupai Nation. Red Butte, including the Canyon Mine location, was determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places as a Traditional Cultural Property in 2009.

Havasupai council member Tilousi testified at the hearing, “We are the most impacted community in the front lines of this contamination and we were never given the opportunity to provide comment and I think that’s wrong. Our most sacred site, our most special sacred mountain, has been taken away from us and has been completely contaminated. We can no longer go over there and do our ceremonies that we’ve done for many centuries. We can no longer pick the sage and the cedar and burn it.” stated Tilousi.

In response to the desecration of Red Butte ADEQ stated, “State law does not allow the Department to include non-air quality requirements in the processing of these permits; however, EFRI is required to meet any and all other applicable state and federal requirements for protecting these resources and properties.” No laws currently ensure protection for sacred sites on federally held lands.

One comment submitted to ADEQ asked the department to conduct calculations to determine mine related emissions throughout Arizona along haul routes. They responded by stating, “ADEQ cannot look at off-site truck emissions when making a permitting decision.”

Several commenters requested that ADEQ perform an assessment of cumulative effects of radon gas, radiation, and radioactive dust in the Grand Canyon region. The department stated, “State law does not allow the Department to consider results of a study like this in a permitting decision for a specific site.”

“I feel that human lives are more important that profit. Water is more important than profit.” stated Carletta Tilousi at the hearing, “I would like for you to seriously look at what you have before you before you give that approval again to the mining companies.”

The uranium mines threaten to further contaminate the Colorado River which flows through the Grand Canyon. More than 40 million people rely on water from the Colorado. According the US Geological Survey, 15 springs and five wells in Grand Canyon watersheds already have high levels of radioactive pollution due to historical uranium mining in the region.

EFRI states that the “Canyon Mine is the highest-grade uranium mine in the US.”

Canyon mine production rate is 109,500 tons per year of uranium ore. The company is also permitted to stockpile up to 13,100 tons of uranium ore at Canyon Mine. The radioactive storage piles will be watered to control dust “and if this is shown to be insufficient” reduction of the storage pile size may be instituted, construction of wind barriers, or tarps could be placed over the storage piles.

Canyon mine

In October 1984, Energy Fuels Nuclear submitted a proposed Plan of Operations to mine uranium from the Canyon Mine claim on Kaibab National Forest Service lands. The final Environmental Impact Statement was issued in 1986, approving the mine. Though no mining occurred, preparations began immediately following that decision. The Havasupai Nation and others sued but lost the case in 1991. In 1987, a group called Evan Mecham Eco Terrorist International Conspiracy or EMETIC, cut 29 power line poles at the Canyon Mine costing the company $200,000. Due to falling uranium prices, the mine was shuttered until Denison Mines, Canyon Mines’ former owner, informed the Forest Service that they intended to resume mine development in 2011.

In 2006, the price of uranium began rising and as a direct result, thousands of new claims for uranium mines were filed around the Grand Canyon. In 2009, this threat prompted the US Secretary of the Interior to impose a 2-year moratorium for new mining claims on 1 million acres of federal lands surrounding the Grand Canyon. The moratorium was extended to a 20-year halt on new Grand Canyon uranium claims in 2012. This ban would be made permanent through a legislative proposal to establish the Greater Grand Canyon Heritage National Monument. Though, neither the moratorium or proposed National Monument prevents existing uranium mines, like the Canyon Mine, from operating.

On October 27, 2016, EFRI announced that it has located high-grade copper while drilling the shaft at Canyon Mine. The company is now evaluating whether or not it will recover the copper as a “by-product” of uranium mining. EFRI announced that it’s shares were up nearly 8% on Wall Street after it announced copper was found at the mine.

“We have not been informed or properly consulted with about any additional discovery of ore.” stated Tilousi, “If that is the case we need to be consulted with immediately by the mining company and Kaibab Forest Service.”

The Kaibab National Forest, which approved the mining based on the antiquated 1872 Mining Law, has been involved in litigation regarding Canyon Mine since March 2013. In 2015, the U.S. District Court found in favor of the U.S. Forest Service in a lawsuit filed by Grand Canyon Trust, Center for Biological Diversity, Sierra Club and Havasupai Tribe.

On April 14, 2015, the Havasupai Tribe filed an appeal to the 9th Circuit Court, the Grand Canyon Trust, Center for Biological Diversity and Sierra Club followed suit. Oral argument in appeals regarding the Canyon Mine will be heard at the 9th Circuit Court in San Francisco, CA on Thursday, December 15, 2016 at 9:30 am in Courtroom 4. Appeals regarding the case over the 2012 mineral withdrawal will be heard immediately after.

There are more than 15,000 abandoned uranium mines (AUMs) located throughout the entire US. Clean Up The Mines, which has proposed legislation to address AUM clean up, advocates that clean up of abandoned mines must occur immediately.

“Native American nations of North America are the miners’ canaries for the United States trying to awaken the people of the world to the dangers of radioactive pollution”, said Charmaine White Face who works with South Dakota based organization Defenders of the Black Hills and Clean Up The Mines.

South Dakota has 272 AUMs which are contaminating waterways such as the Cheyenne River and desecrating sacred and ceremonial sites. An estimated 169 AUMs are located within 50 miles of Mt. Rushmore where millions of tourists risk exposure to radioactive pollution each year. Indigenous communities have been disproportionately impacted as approximately 75% of AUMs are located on federal and Tribal lands.

“Colonization isn’t just the theft and assimilation of our lands and people, today we’re fighting against nuclear colonialism which is the theft of our future.” stated Morgan.

At a recent Native American Forum on Nuclear Issues held in Western Shoshone and Southern Paiute lands, Leona Morgan of Diné No Nukes stated, “When the US has over 15,000 abandoned uranium mines, it makes no sense to continue making more radioactive waste when we have no where to put it. Instead of spending billions of dollars on weapons modernization and subsidizing aging nuclear reactors, we need to start using those funds to clean up contaminated areas. It starts by leaving uranium in the ground.”

“Colonization isn’t just the theft and assimilation of our lands and people, today we’re fighting against nuclear colonialism which is the theft of our future.” stated Morgan.

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.