On January 10, 2017 Argentine armed forces opened fire on a community of Mapuche indigenous people in the Chubut region fighting to reclaim ancestral lands currently in the hands of the multinational corporation Benetton. According to local news, close to 200 gendarme guards blocked Highway 40 and proceeded to attack the community of Lof en Resistencia del Departamento de Cushamen, which comprises fewer than two dozen adults and five children.

The attack left most of the community residents injured, two in a critical state. The armed forces ransacked the main house where the women and children were hiding, and detained them. At least ten members of the community were arrested and nothing has been heard from them since. Among the little news available about the events were reports of harassment and physical abuse of the women and children.

This brutal intervention constitutes a violation of Argentine law 26894 on the possession and property of land, which prohibits any eviction of indigenous people until November 2017. It has been severely condemned by Amnesty International, which called for “comprehensive and impartial investigations into the acts of violence” and published a list of actions which can be taken to pressure the Argentine government. A petition entitled “basta de repression al pueblo Mapuche” (enough repression of the Mapuche people) is currently in circulation.

Following is an investigation carried out in 2016 in Lof en Resistencia del Departamento de Cushamen. It recounts the community’s struggle, their organization and their dreams. The people interviewed for this article will remain anonymous for reasons of security. At their request, the word “peñi” (brother) is used for male interlocutors and the word “lamgen” (sister) for females.

—

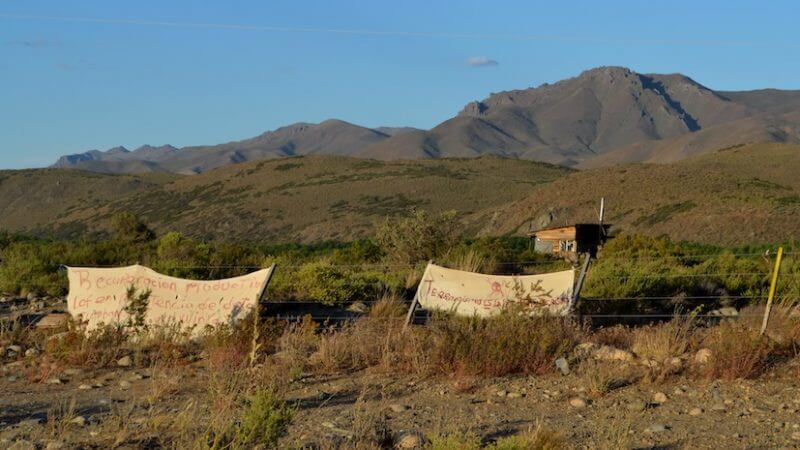

Somewhere along Route 40, in the middle of the desert-like Patagonian nowhere, stands an abandoned-looking wooden shack. All of a sudden, from this postcard-like scene emerges a hooded figure. He looks young. His clothes are ripped. His skin is dark. He comes up to the barbed wire fence at the roadside and stands guard. He takes a moment to rearrange a few sheets hanging over the fence, bearing slogans in red paint: “Land owners keep out”, “Territory in recovery”, “Anti-terrorism law is terrorism”.

The shack is a guard post where the Mapuche people from the community of Lof en Resistencia keep watch day and night to prevent the interventions of local police. Lof en Resistencia is one of many indigenous communities in the Chubut region trying to reclaim ancestral lands currently in the hands of multinational corporations such as Benetton, Lewis, CNN and The North Face. The story has received little local media coverage since the start of the occupation in March 2015. More alarming is the lack of international coverage, as these events occur in the context of a complex global struggle that pits indigenous people against multinational corporations and extractive industries throughout the world. Indeed, between indigenous land rights, private property law and international norms, these disputes over land ownership constitute an intractable legal puzzle that no one has yet been able to solve.

This particular David-and-Goliath battle features a handful of indigenous people on one side and the Benetton Group on the other. The Italian textile giant, better known for its marketing campaigns promoting human rights, peace and ethnic equality than its controversial possession of 900,000 hectares of Patagonian land, has been the subject of a few scandals in the past. In 2002, the company was responsible for the violent eviction of the Mapuche community of Santa Rosa Leleque, which sparked a wave of international indignation.

Today, a year and a half after beginning their occupation, Lof en Resistencia can accommodate more than 15 people, from toddlers to elders. They also receive numerous visits from other Mapuches in the region involved in the fight, who participate in the daily activities of the community. The layout of the community compound is ingeniously simple. The sloping area where they have set up camp is visible neither from the road nor the guard post. In case of emergencies, the person on guard duty blows a horn-like traditional instrument to raise the alarm.

From the guard post, you walk down through thorny Patagonian scrubland, cross some abandoned railroad tracks and climb a slope before the two big wooden houses erected by the community become visible. Roofs of rusty old steel plates sit on top of them, reflecting the sunlight. Each house has a chimney made of stones and mud for cooking and heating purposes, but despite efforts to insulate the houses on the inside living conditions are extremely harsh, particularly in winter when temperatures can drop to -10 degrees C. Slightly further downhill flows the river Leleque, and on the riverbank is a vegetable garden, a spot where the women do the laundry and fences have been built to keep lost sheep from the neighboring Benetton farms.

While Lof en Resistencia’s goal is to become completely self-sufficient and autonomous, the community still depends on a support network to bring them essential commodities from the nearest town, located 100km away.

Less than two centuries ago, the Mapuche people lived freely in Puelmapu, an independent indigenous region known today as Patagonia. Between 1878 and 1885, the Argentine government conducted a brutal military campaign known as La Conquista del Desierto (The Conquest of the Desert) to take over the region and incorporate it into the Republic of Argentina. In the aftermath of their victory, Argentina rewarded foreign enterprises for their financial help with parcels of Patagonian land. One of these, the Argentine Southern Land Company, was bought by Benetton in 1991, along with the property rights to nearly a million hectares the company owned in the Chubut region. Since then, the Italian multinational has been using the area for petrol and mining exploration, wool production and forest exploitation.

However, the last few years have witnessed a growing number of indigenous occupation movements all across Patagonia. The people of Lof en Resistencia claim the land they are currently occupying belongs to them ancestrally and is therefore rightfully theirs. “This region was considered free indigenous territory only 135 years ago. Our great-grandparents used to live on this land. And then one day, the military came and they slaughtered everybody,” explains the longko (chief) of the community. The Conquest of the Desert left thousands of indigenous people dead and around 14,000 were placed in servitude, forced to work on the very land that had been taken away from them. Shortly after, a merciless repression against the Mapuche ensued.

Adriana, who works for the community’s support network, has agreed to reveal her name. She talks about the oppression of the Mapuche as described to her by elders: “On the farms of the new latifundistas, they [the Mapuches] were forbidden to speak their own language. The huincas [white men] would cut off the tongues and ears of Mapuches they heard speaking Mapudungun. They would also cut men’s testicles and women’s breasts to prevent reproduction. It was a real campaign to annihilate our identity, to make people reject their heritage and their roots.”

Such testimonies have been passed down orally in Mapuche communities from generation to generation, as the Mapudungun language does not have a writing system. These stories of persecution, torture and massacre are thus deeply entrenched in their collective memory, and have now become an integral part of their identity.

Today, the Mapuche are faced with a new kind of oppression—social exclusion. The indigenous people who have settled in the scattered Patagonian towns live in extreme poverty. Most of them are unable to find jobs, and those who do are used as cheap labour. Adriana’s daughter remembers the constant bullying she experienced at school: “They would call me stupid, poor, filthy… just because I am Mapuche.” Adriana says she was falsely accused of sexually abusing her students at the dance school where she taught a few years ago. She was fired, despite her students’ protests, and has not found another job since.

For the people of Lof en Resistencia, social inequality and injustice was of one the main triggers for the exodus to their ancestral land. “The Conquest of the Desert didn’t really end in 1885; it just took on a different form. . . . We are much better off living out here in the end,” explains the longko, staring deeply at the immense surrounding plain. The charismatic leader describes how, growing up in a poor family, he used to spend all his time at the local library instead of in the streets like the other kids, who would eventually become delinquents. He believes books are what saved him from ending up in prison. Distrustful of the “neo-imperialist” Argentine educational system, he has taken it upon himself to supervise the education of the youngsters in the community.

But far beyond the conditions of their lives and the ancestral rights they defend, there is an even deeper wretchedness felt by these indigenous people, and it is this feeling that compelled them to initiate the occupation. The word Mapuche is a compound of the words “mapu” (the earth) and “che” (people). Nature lies at the very core of their belief system and spirituality—a way of life, which, according to them, the huincas are incapable of understanding.

Mapuche ceremonies are conducted by the machi (shaman) who represents the highest spiritual authority and is responsible for connecting the spirit world to the human one. The people of Lof en Resistencia have the utmost respect for the natural resources available to them. Special rituals are carried out, for instance, after killing an animal or taking water from the river, and fires are only ever made with deadwood. Life in industrialized cities is incompatible with Mapuche values, hence the need among some to return to their ancestral land. “If a mining company were to come here and destroy that hill over there to extract the resources inside, it would be like… amputating your leg or your arm. One becomes ill. It’s as simple as that. We have a strong spiritual connection with the Earth, that’s why we have to defend it at all costs,” declares a young lamgen.

Remoteness and isolation do not prevent people of Lof en Resistencia from having an extensive knowledge about the world. From the war in Algeria to the 2016 US elections, Max Weber, Islamist terrorism and the dissolution of Yugoslavia, debates are never-ending and ubiquitous. This knowledge of politics, history and philosophy allows them to articulate their ideas with caution and clarity. A peñi explains: “You could say that we’re anti-capitalists and anti-imperialists. But we don’t want labels. We don’t want to be associated with any movement. We are not Marxists, eco-activists, or indigenists. We are just Mapuches. We’re fighting because today’s extractivist economic system is destroying the Earth, which we need to live in balance with.”

As soon as they step out of the rukas (houses) the Mapuches put their hoods back on, or tie a t-shirt around their faces—a simple precaution to prevent the authorities from identifying them. They say there have been disappearances in the past, and as a result they fear for their loved ones. They laugh at the label the government has given them: “terrorists”. This label has, however, proven very useful in legitimizing the brutality of local police forces, which are justified as part of the “fight against terrorism”. This is a strategy known all too well in the United States and some Western European countries, where it’s used as a smokescreen to hide abuses of power and violations of human rights. In front of the main house, two little boys are role-playing, fighting over who gets to be the good guy. “I want to be the terrorist! You be the police this time!” says one. “No!” screams the other “I don’t want to be the police! I want to be the terrorist.”

Feelings of tension and insecurity are omnipresent in the community, with good reason. In the past, there have been many attempts at eviction as well as acts of intimidation, perpetrated not only by the authorities but also by civilians. However, the people from Lof en Resistencia are far from giving up. “If we didn’t believe it was possible to regain the land, we wouldn’t be fighting,” says one lamgen. “If it’s not us, it will be our children, but there’s no turning back now. We already know what torture is, what prison is, what death is. We are not afraid.”

Their strategy is simple: a slow, gradual occupation of the land. As the longko says, “We believe that each community should follow their own path to self-determination. . . . We want to rebuild our Nation. You could say that we are in a process of self-decolonization. We want to throw out the current ‘land owners’ and reconstruct the Puelmapu. We are not looking to overtake the huinca state. Frankly, we want nothing to do with the State. We don’t want to negotiate, because there is nothing to negotiate. This land is ours.”

Lof en Resistencia’s act of occupation might seem small, but its impact might not be. As one peñi puts it, “We are the annoying mosquito on Benetton’s arm. Actually… it goes much further than that. An occupation like ours puts in danger the very existence of other companies in the region, both national and transnational. This kind of occupation always generates replicas overtime in other communities. We are slowly planting the idea of regaining territorial control.”

Benetton declined to comment for this article, but in a position statement issued by the Benetton Group in December 2010 regarding the occupation of the Santa Rosa Leleque community, the company said it “found itself unwittingly involved” in a “historic problem relating to the creation of the Argentinean state in the 19th century and its relationship with the native populations who lived there before the birth of the state.”

Legally, the issue is a real jigsaw puzzle. While the company was probably aware of the historical circumstances under which the Argentinean Southern Land Company Ltd came to possess the land, can the Benetton Group really be held accountable? What about the property rights Benetton is brandishing in the courts? On the other hand, article 75 (subsection 17) of the Argentine National Constitution clearly recognizes the pre-existence of indigenous people in Argentina and guarantees their possession of lands they traditionally occupied. Argentina has also ratified the ILO Convention 169, as well as the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, guaranteeing indigenous people essential constitutional rights. According to Human Rights Watch and the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, however, Argentina hasn’t respected either piece of international legislation.

The issue also goes beyond mere legality. Benetton bought the 900,000-hectare parcel in 1991 for 80 million dollars. The value of that land has since increased tremendously. It is inconceivable to think the Italian company would easily give it back to the Mapuche, which means the land would have to be bought back by the Argentinean government with taxpayers’ money, something to the people in the region are firmly opposed.

This issue is neither narrow in its scope nor confined in its geography: it goes beyond the issue of indigenous rights and the region of Patagonia. The occupation of Lof en Resistencia takes place in the context of a global struggle carried out by indigenous people throughout the world, fighting for the sovereignty of their land and its natural resources, endangered today by well-known multinational corporations and the activities of extractive industries.

No agreement has yet been reached, and the clock is ticking. According to Argentine Law 26894 on the possession of land, all evictions are technically prohibited until November 2017, giving the government less than a year to find a solution. Meanwhile, Benetton is standing its ground, while indigenous occupation movements are spreading across the region. These struggles should serve as nothing less than an inspiration to those seeking alternatives to an unsustainable neoliberal economic system that favours corporations over people, profits over natural resources and individuals over communities.

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.