The camp smelled like smoke and urucum, a plant used for body painting. A defiant energy pulsed through the crowd. We could hear chants, ritual mantras, and ceremonial crying.

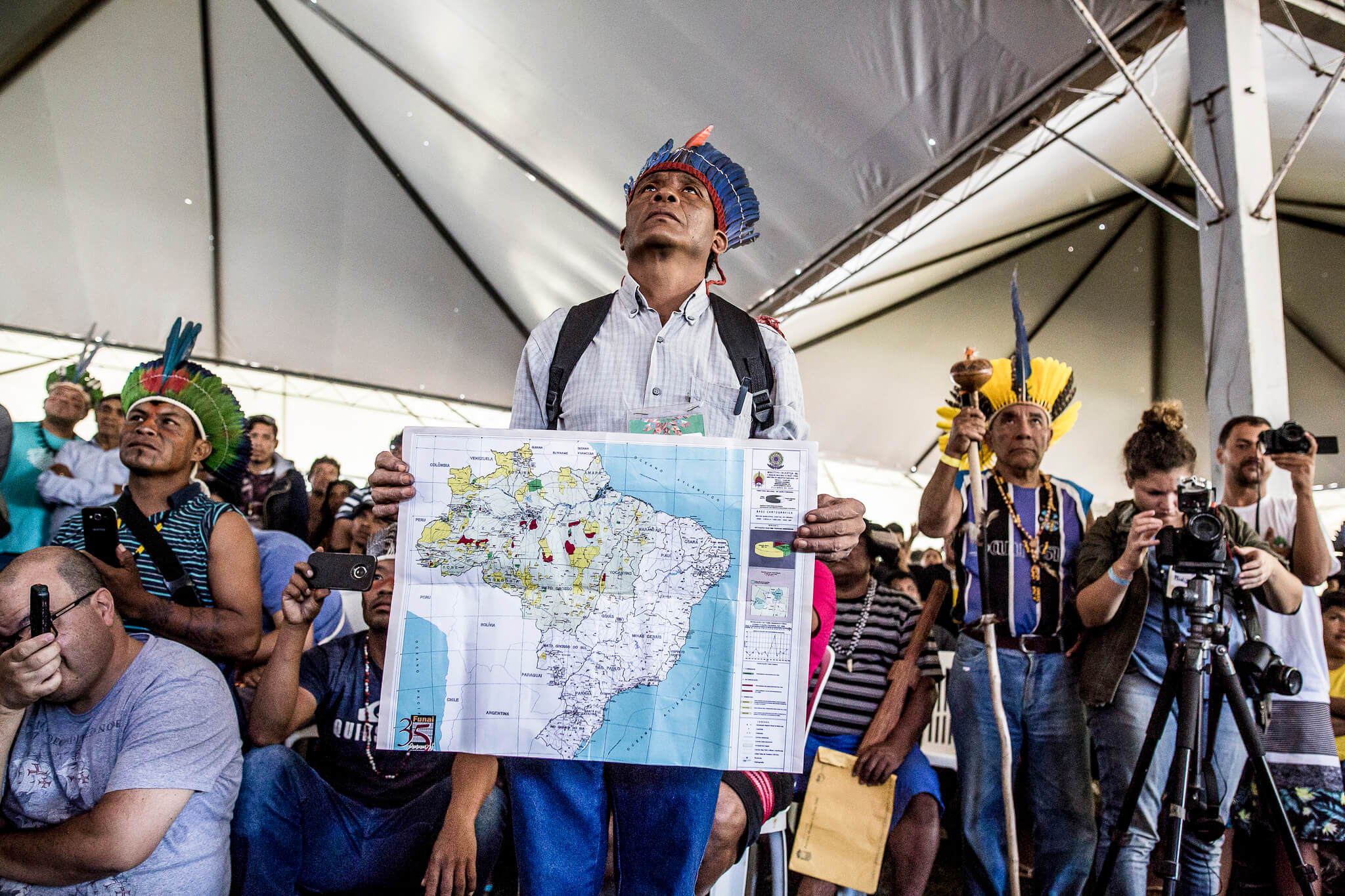

The place resounded with the voices of the more than 3,000 indigenous people from more than 100 different groups from all over Brazil, who gathered for the five-day 2018 National Indigenous Mobilization, held from April 23 to 27 in Brasilia, the Brazilian capital city.

Also known as the ‘Free Land Camp’ (‘Acampamento Terra Livre’, in Portuguese), the sit-in is a yearly event organized by the Articulation of the Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB, in the Portuguese acronym). This year’s was its 15th edition.

According to the last Brazilian demographic census, there are 305 indigenous populations in Brazil, speaking 274 different languages. Together, they number almost 897,000 — approximately 0.47% of the country’s 200-million-strong population.

Most of them are scattered over thousands of villages, from north to south of the national territory, located in the 715 Indigenous Lands already regularized and formally recognized by the federal government. There are more than 800 cases of indigenous lands awaiting regularization.

Photo: Mídia NINJA/flickr (Some Rights Reserved)

The movement has been facing a series of political setbacks, which gave renewed thrust to this year’s mobilization.

The Brazilian National Congress, whose majority is currently dominated by supporters of the agribusiness sector, are trying to approve a bill package that would undermine the rights of indigenous peoples guaranteed by Brazil’s 1988 Constitution and other international laws, such as Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization.

In the current complex political situation in Brazil, under the controversial administration of president Michel Temer, representatives of the agribusiness sector have gained even greater foothold and managed to also occupy other levels of government.

Only days before the Free Land Camp took place, President Temer yielded to pressure from a ruralist caucus and fired the president of the National Indigenous Foundation (FUNAI), replacing him with someone more agro-friendly.

The government’s reluctance to grant formal recognition of indigenous lands’ boundaries and the criminalization of the movement’s leaders were major points of concern and grievance for those who gathered in Brasilia.

Photo: Mídia NINJA/flickr (Some Rights Reserved)

Kretã Kaingang, an indigenous leader from the state of Paraná and coordinator of the indigenous program of 350.org in Brazil, recalled the kind of threats he has faced. “I was imprisoned for a time, accused of crimes that were not proven and I have been prevented by a judge from approaching the land where I was born. For four years I couldn’t step on the place where my umbilical cord is buried,” he said.

In September 2017, Brazil’s attorney general issued a legal opinion asserting that only indigenous peoples who were occupying their territory on the day the 1988 Constitution was promulgated should benefit from the recognition of their right to land.

Known as the “time limit” thesis, and sometimes called the “genocide opinion“, it has been endorsed by President Michel Temer. Should it ever become law, it would severely cripple the recognition of new indigenous lands.

The night fell as the indigenous leaders stood in vigil in front of the federal government building. At one point, the crowd raised candles and stopped their activities to listen to a lament sung by one of the indigenous women. It was a mourning ceremony.

Photo: Mídia NINJA/flickr (Some Rights Reserved)

On the following day, the Esplanade of Ministries, the main route where all federal government buildings are located, was occupied again by protesters, who marched towards the seat of the National Congress.

With paintings and adornments, dancing and singing war cries, indigenous Kaingang, Guarani, Guarani-Kaiowá, Guarani-Mbya, Xucuru, Pataxó, Munduruku, Awá-Guajá, Guajajara, Marubo, Xerente, Xavante, Kayapó, Tenetehara, Tembé, Tucano, Krahô, Kanela and many others demanded the process of demarcation of their lands be resumed and asked for respect for their rights, as enshrined in the 1988 Constitution.

Indigenous leaders carried banners with messages targeted at the authorities: “Demarcation Now!”, “No fracking in our lands!” and “Guarani resists”. Other signs called out the destruction of territories, rivers and natural resources by giant infrastructure and energy projects.

Photo: Mídia NINJA/flickr (Some Rights Reserved)

“We have only one objective here: to resume the process of demarcation of our lands. Many of our relatives could not join us, so we came to represent our communities,” said Kretã Kaingang.

During the demonstration, the street was stained red, symbolizing the blood shed by indigenous people during acts of repression and violence which are considered by many a continuation of the historical genocide perpetrated against them during colonial times.

“‘The trail of ‘blood’ we leave represents the violence and attacks imposed by the state to the original peoples of this country. Several invasions, threats, and assassinations have been occurring in Brazil, in addition to a cruel process of criminalization of our leaders. But despite this problematic conjuncture, we will always resist and fight, as we learned from our ancestral warriors,” said Chief Marcos Xukuru of Pernambuco.

Joênia Wapichana, the first indigenous woman and indigenous lawyer to stand up in the Federal Supreme Court, recalled what is really at play: “The fact that the Executive Branch has an instrument to restrict the right to demarcation puts the lives of all indigenous peoples at risk, whose subsistence depends directly on the land and everything it gives.”

Photo: Mídia NINJA/flickr (Some Rights Reserved)

“The demarcation of our lands equals their preservation. We have heard reports from our relatives from all regions about invasions pursued by loggers, prospectors, grabbers and state enterprises. What we want is to ensure the lives of future generations. We fight here not only for us indigenous peoples but for the Brazilian society as a whole,” said Tupã Guarani Mbya, from the Indigenous Land Tenondé Porã, in São Paulo.

For the chief Juarez Munduruku, indigenous peoples are like trees. “There’s life in the trees just as there is in us. If you kill them, they die and never come back. If a logger kills a ‘cacique’, a story ends.”

He recalled that in the middle of the Tapajós River, in the Amazon, where his territory is located, there are plans to build 43 big hydroelectric plants, which will dam one of the largest rivers in the country, a sacred place for his people. Two of these projects have already been implemented, and there are plans to also build 30 ports to transfer monoculture soybeans, in addition to mining and illegal logging.

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.