While the annexation of Crimea has been discussed from multiple view-points in the European media, and largely from a single view-point in the increasingly state-controlled Russian media, relatively little attention has been paid to those who have by far the best claim to be the native and ultimately sovereign inhabitants (‘korenniy narod’) of the peninsula: the Crimean Tatars. The Crimean Tatars’ political leader, Refat Chubarov, proposed in March 2014 that an autonomous region be established for his people – a long-standing aspiration given renewed urgency by the ‘change of masters’ from Ukraine to Russia. A slow but constant exodus of Crimean Tatars followed the Russian occupation, due to the deep-seated unease with which Tatars view the authorities in Moscow.

The reasons for this unease – aside from the less than enthusiastic respect for cultural diversity in, say, Russian-controlled Transnistria (part of Moldavia, and therefore home to Moldovians/Romanians and Gagauz as well as Russians) – run deep. Soviet crimes against the Chechens, owing to their colourful and ambiguous place in the annals of history, as at once freedom-fighters and gangsters, and as leaders and rabble-rousers of other less ‘excitable’ nations of the North Caucasus, are fairly well-known. At the cost of several hundred thousand deaths, the small nations of the North Caucasus (the Chechens especially) were forcibly removed en masse to Siberia, under Stalin. In the Chechens’ case, the intention was to entirely eradicate the Chechen nation – not by outright genocide (although the number of deaths caused in the space of a few years would largely justify the term) but by dispersal and acculturation, leaving the whole territory of Chechnya empty, to be allotted to Russians and other regime-approved Soviet nationalities. (Cossacks in particular were viewed as a hardy and suitable replacement stock for the ‘reactionary tribes’ the Soviets were sadly obliged to destroy).

Less well-known is that the Caucasus was not entirely alone in this form of ‘collective revenge’ for alleged disloyalty to the state. In the long term, the Crimean Tatars were impacted more grievously than even the Chechens, for two reasons: their population was comparatively small to begin with; and denial of the right of return was maintained against them for far longer – for the entire duration of the Soviet Union, in fact. The right of return was only established with Ukrainian independence. Crimean Tatars returned to their homes from 1989 onwards. Just as their removal had been an especially total ethnic cleansing, their return was comparably wholesale: the greater part of the Crimean Tatar nation (almost 300, 000) came home. Now many are leaving once again.

There was a marked contrast between Lenin’s view of the non-Russian nations and Stalin’s. Lenin actively promoted a policy of ‘nativisation’ (коренизации/korenizatsii), enshrining the sovereignty of Autonomous Republics in law. The ‘freedom’ permitted was in many cases more apparent than real, but the languages and institutions, along with the lives, of non-Russians were respected. In October 1921, the Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (A.S.S.R.) of Crimea was formally established. As J. Otto Pohl notes:

This administrative unit actively promoted the cultural autonomy of the Crimean Tatars, who made up about a quarter of the territory’s population. Both Crimean Tatar and Russian were official state languages of the Crimean ASSR. On a local level the Crimean ASSR had 144 villages which used Crimean Tatar as their administrative language. The territory also possessed a myriad of Crimean Tatar cultural institutions including four teachers’ colleges, journals, newspapers, museums, libraries, theaters, and an Oriental Institute at Tavrida University specializing in Crimean Tatar language and literature. The Soviet government’s active promotion of Crimean Tatar national development in the 1920s contrasts sharply with Stalin’s later attempt to destroy the Crimean Tatars as a people.

If we were to draw any comparisons between Lenin, Stalin and Putin on nationalities policy, the last-mentioned would emerge more Stalinesque than Leninist.

The deportations – whether of Chechens, Ingush, Crimean Tatars, Meskhetian Turks, or even Kurds and Pontic Greeks – began in 1943, and continued until at least 1949. Roughly a quarter of those deported died within five years, mainly through starvation and disease. In some cases, rather than the likely death-sentence of transportation, straightforward massacre was practised: one of the more notorious instances took place in Khaibakh, Chechnya, where 600 people, deemed too old, too young or too sick to be transported, were boarded up in a stables block and burned alive. It so happens that among the victims of the massacre were Dzhokhar Dudayev’s grand-mother, aunt, and two cousins (aged eight and eleven). This very likely contributed to Dudayev’s alleged ‘fanaticism’, as the first President of the Chechen Republic (Ichkeria), in confronting the Russian army head-on during the first Russian invasion (1994-1997). (Dudayev himself was assassinated by the FSB in 1996, a year before his Chief of Staff, Aslan Maskhadov, dramatically drove the Russian army back out of the capital, Grozny, and effectively forced Yeltsin to come to terms. The conflict was settled due to some impressive diplomacy by Alexander Lebed, but later deliberately rekindled by Putin, for reasons even less comprehensible than Yeltsin’s).

While the massacres and deportations ceased upon Stalin’s death, the small nations he had marked down for ‘liquidation’ had to wait for Khrushchev’s reforms from 1956 onwards (following the somewhat inaccurately-dubbed ‘secret speech’, in which Khrushchev first acknowledged Stalin’s crimes and abuses) for permission to return to their own countries.

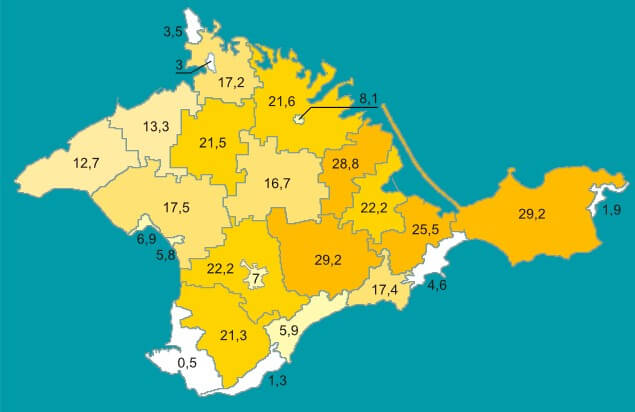

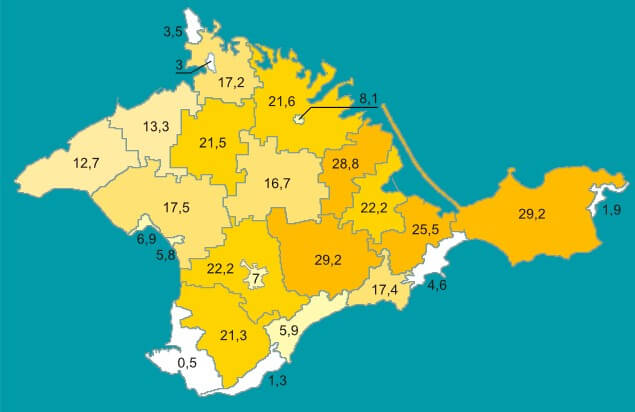

Crimean Tatar population density, according to the 2001 Ukrainian census: darker yellow indicates higher population (By Riwnodennyk. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons)

Yet even then, the Crimean Tatars were excepted from the general amnesty. One of the reasons that the Crimea was ethnically cleansed in the first place is doubtless a large part of the rationale for its recent reinvasion: a Black Sea port offers a huge strategic advantage for Russia. The extraordinary vindictiveness of Russian policy towards the Tatars over decades – now renewed once again – is thus grounded in hard-headed real-politik. This is also the reason for the broad direction of advance of Russian proxy forces (so-called ‘secessionists’) in eastern Ukraine recently: namely towards Mariupol, from where the intention was/is to link up Donetsk, Luhansk and Crimea (and perhaps Transnistria) with the coastal territory in-between, to create a Black Sea corridor under Russian control. The fatuous rhetoric about ‘fascists’ in Kiev is ironically almost identical to the reasons given by Stalin for the deportations – it was eventually acknowledged in 1967 that the ‘Nazi collaboration’ charges had been fabricated. (Crimean Tatars were the second largest contingent, relative to overall population, in the ranks of the partisans who had resisted the Germans). It is clear, to be even-handed about this, that Putin has read his Russian history attentively – read it and indeed recycled it. (Though it must also be acknowledged that Ukrainian as well as Russian units had launched unprovoked attacks against the Tatar population during the war).

All told, nearly 200,000 Crimean Tatars were removed from their homeland. The official figure given in a Soviet report is 183,155. To quote J. Otto Pohl,

In addition to these exiles, the NKVD also separated 11,000 young Crimean Tatar men from their families and sent them to perform forced labor. The Red Army conscripted 6,000 of these Crimean Tatars into construction battalions. The remaining 5,000 became part of an 8,000 man special contingent of the labor army requested by the Moscow Coal Trust. In a mere three days, the Soviet government forcibly removed 194,155 Crimean Tatars from the Crimea. The NKVD successfully expelled virtually the entire Crimean Tatar population from its ancestral homeland. To this day it remains one of the most rapid and thorough cases of ethnic cleansing in world history.

To the scene of which, we might add, Putin has returned as a dog returns to its vomit.

This is why Crimea’s 300,000 returned Tatars are finding something a little too familiar about all of this – why thousands have fled the country already and why there is a greater urgency than ever for the full restoration of Tatar constitutional and cultural rights. It might also go some way to explaining the somewhat anomalous presence of Chechen fighters alongside the Ukrainian armed forces and irregulars (apart from the obvious wish to give Moscow a bloody nose for its continued occupation of Chechnya itself, and its fulsome backing of the murderous dictator Kadyrov). However deployed, on the eastern front, they will not forget what is haunting the Tatars beyond that short stretch of Black Sea coast, since they know its ghost all too well.

In terms of recovering the Crimea, that seems hugely unlikely in the medium-term: In the absence of any dependable ally, Ukraine can hardly do anything but commit its full military resources to the prevention of further Russian advances in the east. It is all the more necessary, therefore, that no formal acknowledgement of the Russian puppet-state in Crimea be considered – since this would leave no recourse for the Crimean Tatars to present their case to international attention, for instance via the U.N. (A paltry platform but better than nothing). Few ‘statesmen’ will even waste their breath on the rights of minorities once they can be deemed ‘an internal matter’ (again, just ask the Chechens).

The re-establishment of a Crimean Tatar homeland is a matter of simple historical justice – and for this very reason, it is doubtful any major power will give it much consideration. But lacking a secure national territory, and now lacking even a patron state, so to speak, to count as an ally, moreover lacking any kind of armed movement for its defence, the spectre of the world’s short attention-span leaving them behind is what now drives the exodus. The story is already in danger of ‘moving on’.

What can we do? Not much. We can make some noise, we can say ‘we’re still watching‘, and we can reassert an unfashionably simple principle – that sovereignty belongs to, and only belongs to, the oldest extant population of a country. It can scarcely be questioned that means the Tatars. We can go beyond the faulty and less than fully human mind-set of so many of our leaders who say ‘yes but that was all so long ago‘ when it is more profitable to do nothing, and ‘well, it’s too late now‘ when it is less embarrassing to look away or forget. As many philosophers have noted, it is difficult to clearly distinguish memory from thought itself – in the age of instant everything, not forgetting, not being ‘sensible‘, not ‘moving on‘, even nursing just a little bit of a ‘chip on your shoulder‘ is a skill worth holding onto, so that ‘justice delayed‘ need not be ‘justice denied.’

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.