In 2002, Siswo Pramono authored the paper “An Account of the Theory of Genocide (pdf), revealing several critical flaws in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. For one, the paper shows how the Convention was designed to “allow an exit strategy for those planning a future policy of genocide;” while also protecting the majority of perpetrators in the Modern World from being charged with this most abhorrent crime.

In the interests of pursuing Justice and extending dialogue on the matter of genocide, it’s important for us to be aware these (state-designed) flaws; in addition to the alternative, more realistic definition of genocide he outlines.

“Paralysis by Design”

The first major loophole Pramono reveals is found in the first line of Article 2 of the Convention, which reads:

“In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such…”

“Intent” is the magic word. The entire definition of genocide hinges on it. Frequently, on one particular side of the mainstream debate, the presence of “intent” is regularly applauded because it can mean that a genocidal act doesn’t actually have to be executed in order for genocide to actually occur. Professor Ben Kiernan, author of the book “Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur” expressed this very point while being interviewed on Voices on Genocide Prevention a few weeks ago; explaining that no one even needs to get hurt in order for there to be genocide. ‘There need only be an intent.’

While this is true, Pramono explains that at the same time, all the perpetrator has to do is prove they did not intend to commit genocide. Then, by definition, genocide must not have occurred. Let’s call it the “whoops clause.”

I’ll admit, this is a relatively minor issue, but then we’re not talking about opples and banonos are we? We’re talking about genocide in law. Since when is such an abstract, moral value like intent reasonable in law? Imagine some guy commits rape, but oh that’s ok, he didn’t mean it. Whoops.

Does that sound reasonable to you? Nor should the presence of “intent” in the legal definition of genocide.

Pramono argues that instead the definition should be “end-oriented;” that “a standard of knowledge on the course and outcome of genocidal acts” should be introduced to ensure genocidal acts can actually be punished.

Another, much more serious flaw is found in that first sentence—in “the deliberate omission of political group, and hence the corresponding politicide;” “an irony given that more people are destroyed for political reasons than any other. Nearly 170 million people, excluding war dead, were murdered by governments in the last century but, as a consequence of the current legal definition, “only” about 39 million qualified as genocide (Rummel, 1997: 94). What is then the remaining 131 million dead called? And most importantly, who should be deemed responsible for this “crime without a name”, if this is considered a crime at all? Genocide minus politicide is a scandal, if not a conspiracy.”

Pramono ends his paper explaining that “the current political and legal system to deal with genocide is best described as ‘paralysis by design’. The understanding of genocide is simplistic and thus the corresponding treatment to genocide is poor. It is indeed an half-hearted effort to deal with a gigantic, complex crime in which, unfortunately, those who supposed to repress it were or are involved in its commission. As such if a top-down approach led by states (i.e through diplomatic conference) to combat genocide is hart to attain, an alternative bottom-up resistance against this crime must be organised and pursued by civil society.

Such resistance must develop a new understanding, a reformed theory-as-practice, to shape social behaviour towards genocide.”

Redefining Genocide

To that end, Pramono explores what a ‘new,’ more realistic definition should look like. First he describes five major types of genocide:

Progressive (towards the ‘classless’ society),

Reactionary (towards the ‘racially pure’ state or ‘common marketisation’ of the world),

Developmental (eliminating ‘backward’ peoples and their economies),

Retributive (taking revenge); and

Hegemonic (seizing and holding power.)

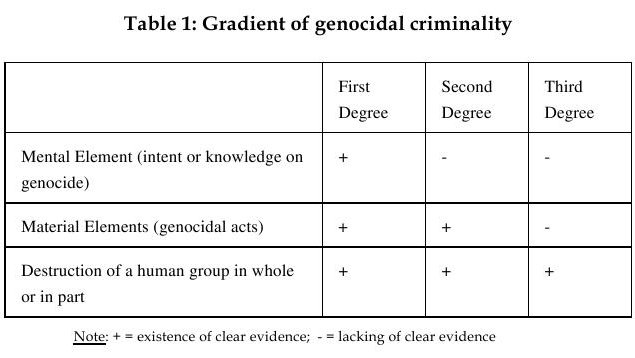

He also outlines a multi-layered gradient of criminality “to narrow the possible obfuscation by the (prospective) perpetrators…”

“…As such, first, if the genocidal mental element —either intent or knowledge— is evidently clear, the furtherance of genocidal acts (actus reus) qualifies as first-degree genocide. This applies to most cases of direct genocide. Second, if the genocidal mental element per se is unclear, while the genocidal acts (actus reus) are evident, the crime qualifies as second-degree genocide. This qualification would help to detect genocide during wars or armed conflicts of any kind. Third, if the genocidal mental element and genocidal acts are lacking, but due to recklessness and negligence, a group or more is inevitably destroyed —in whole or in part— the corresponding acts qualify as third-degree genocide. This would help detect genocide as a “by-product” of such policies as economic development or global capitalism.”

End of Discussion

If “Genocide” is to be anything more than a subject of debate–one fueled by opinion, emotion and fallacy; if it is to be an actual subject of international law then the basic framework outlined here is self-evident.

At the same time, it would be perverse to suggest that before law and debate, genocide has not been a common historical policy—one that continues to be engaged on a regular basis throughout the world Just look at the sheer number of indigenous societies being threatened by development and assimilation schemes. Whether or not there is a deliberate intent, the outcome of these policies are genocidal because they result in the destruction of separate and distinct societies.

For indigenous people the debate is moot. There is no debate; and genocide is not merely some abstract concept we apply to some far away place and time. It’s here and now.

Whether or not the mainstream debate continues or the meaning is changed by people with a conscience (or out of fear of humiliation) genocidal policy will continue being engaged because it is synonymous with colonial and imperialist endeavour.

Thanks to Tim Willard for posting Pramono’s paper on his blog

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.