As winter passes and new life takes hold in New Zealand, indigenous guests from far abroad have arrived to exchange cultural knowledge.

It’s more than 12,000 kilometers from Salem, Oregon, to Dunedin, Otago – an epic journey across the Pacific – but for students like Cherokee Miranda Livers, it’s a pilgrimage for a cultural immersion like no other.

The University of Otago’s first ever Tūrangawaewae, Pōkai Whenua Indigenous Exchange Program is a community-to-community exchange centered not on an academic transaction but an immersive cultural transmission.

“The key word is manaakitanga,” says Tuari Potiki, Director of the Office of Māori Development at University of Otago.

The program runs for 15 weeks and houses international students from the 12 partner universities alongside community-minded Māori tauira, facilitating a lived exchange of tikanga and cultural taonga.

“It’s not about a few poi lessons and a trip to the marae,” says Potiki. “But actually taking part in a living culture, immersing oneself in indigeneity beyond and outside of the classroom.”

Born and raised in Sacramento, California, Livers came late to her indigenous identity, only grasping the implications of heritage upon graduating high school. During a native ceremony in which a Cherokee elder prayed for students, smudged them with sage and gifted each an eagle feather, Livers felt a sense of belonging.

“It was the catalyst for everything that followed,” she says. “I was honored to attend, although throughout the event I was surrounded by a culture and tradition I did not know how to navigate. But this ceremony felt like home. It was strange, awkward at times, but in my heart I felt like I was home.”

But home has its problems. Thirty-five percent of Native students will never graduate high school, and less than 10 percent of Native Americans will ever get a college degree, says Livers. The history of the Cherokee is the history of indigeneity across the continental US and beyond.

As with Māori in New Zealand, first nations people in the United States had no written language, teaching their children through oral traditions. Early colonizers saw this as savage and primitive, systematically stealing children from their communities in an attempt to, as Livers says, “kill the Indian and save the man”.

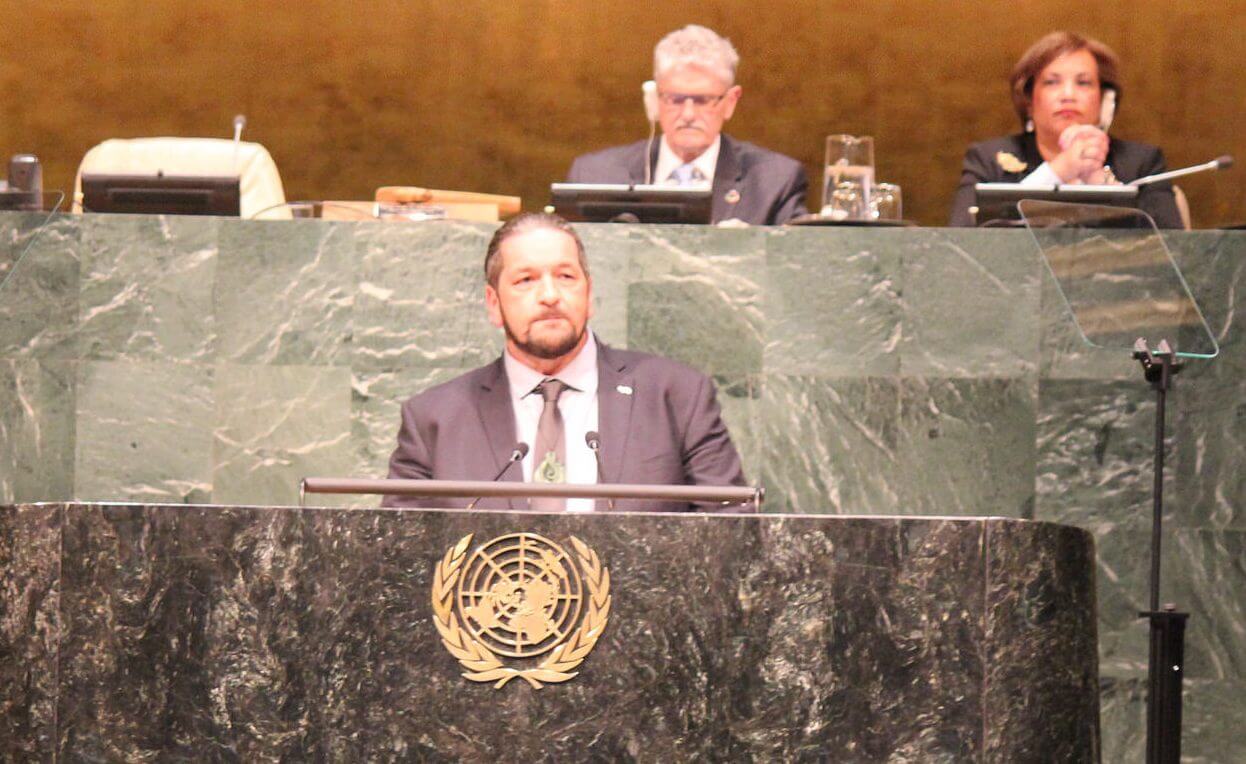

Tuari Potiki at the UN General assembly.

Tuari Potiki at the UN General assembly.

Colonizers also quite literally killed the Indian: slaughtering indigenous peoples, breaking treaties, dispossessing the tangata whenua of their land and cloistering families on marginalized, government-mandated reservations. As you would expect, the implications for an indigenous relationship with colonial education systems were dire.

“When talking about a connection between indigeneity and higher education – especially a historical one – the short answer is that there will always be a very close and weighted connection,” says Livers.

“The long answer is after time passed and we were finally allotted our lands, and given citizenship; after we had fought tooth and nail to keep our culture, language, and heritage alive; after years of trying to maintain our identity while finding a way to live within this new world; after hundreds of years, we have only achieved slight success in increasing our graduation rates for high school alone.”

Here in New Zealand Māori face similar challenges, languishing behind European and Asian students across most educational metrics. Barlow Anderson, a fourth year indigenous development student at University of Otago, says it is often the case in colonized societies that indigenous knowledge is undervalued. Anderson will travel to Canada’s Memorial University in Newfoundland this September to stay with the aboriginal peoples.

“Cultural knowledge, framework and practices aren’t fully acknowledged as a credible pathway in pursuing higher education,” he says. “The lack of equal status between wananga and universities is a good example of this.”

“Indigenous advancement success comes when indigenous people are able to enforce indigenous solutions to address indigenous issues. When indigenous frameworks are recognized as legitimate ways in addressing the problems that many of our indigenous communities face, indigenous advancement will follow.”

But for Livers, the existence of wananga at all is an intriguing difference between the relationship Māori have with the Crown, and that of first nations peoples to the United States government. It’s a case of indigenous communities empowering one another through shared discourse – the true value of any exchange.

“We know that in this life, this society, education is the key to a better life, and we will always push our children toward that brighter future. They just don’t all make it,” she says.

In the United States, native and indigenous families rank among the poorest in the country. Among every other financial burden faced by citizens of the US, college is yet another titanic investment. Bridging that gap, and increasing indigenous achievement at the highest levels of education, is tantamount to Liver’s’ work as a Cherokee.

“One of the main drivers I have for being here is to see how successful the Māori people are in keeping their culture and language alive, how they negotiate with the government, and what programs and systems they have in place to ensure their success. I want to learn and witness all of this, so I can understand what we are lacking back home.”

“Throughout history you will always see the back-and-forth, paradoxical relationship between education and indigeneity. On the one hand we fight against being colonized. Being told to conform – how to act and when, what is and isn’t proper. But on the other hand, we value education like life itself, because for us, in a way, it is.”

This content is brought to you by the University of Otago – a vibrant contributor to Māori development and the realization of Māori aspirations, through our Māori Strategic Framework and world-class researchers and teachers.It was originally published at The Spinoff and re-published at IC with permission.

[/sinoff]

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.