Lee Swepston, Former Senior Human Rights Adviser at the International Labour Organization (ILO), discusses the history of the ILO’s Conventions on Indigenous Peoples.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is a specialized United Nations agency that aims to improve the living and working conditions of people around the world. It was founded under the League of Nations in 1919 as part of the Treaty of Versailles.

Being the oldest of the specialized agencies of the UN system, it is also the first international body to address indigenous issues in a comprehensive manner through establishing the Indigenous and Tribal Populations Convention, 1957 (No. 107) and the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989 (No. 169).

ILO Convention 107 is widely regarded as a pioneering document, however, as Lee Swepston observes in this video, it was also a refection of the time. As such, “it advocated largely assimilationist goals” says Erin Hanson of Indigenous Foundations, “and [it] was written from a perspective that saw Indigenous cultures as lower on the evolutionary scale than those of European origin.”

For example, Convention 107 describes Indigenous populations as “at a less advanced stage” than the colonizers and suggests that “the process of losing their tribal characteristics” is inevitable. The convention extended political rights, such as citizenship and the vote in nations where these rights were absent (Aboriginal peoples in Canada did not receive the franchise until 1960). It also recommended vocational training to help Indigenous peoples enter the (settler-based) market economy. Regarding land rights, Article 12.1 of the convention states that Indigenous populations “shall not be removed without their free consent from their habitual territories”—unless the government wants to develop said territory for their own purposes. Critics argue that such clauses enable nation-states to continue their oppression of Indigenous peoples without consequence.

In the years following its adoption, the limitations of ILO Convention 107 became evident and indigenous peoples themselves began to call for new international standards, prompting the ILO to begin work on revising the Convention.

In 1989, C107 was revised and renamed Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989 (No. 169). Like its predecessor, ILO Convention 169 outlines the rights of indigenous and tribal peoples and the obligations of Nations that ratify it. But rather than support an archaic colonial endeavor like ‘integration’ C169 takes the more reasoned approach that the existing cultures and institutions of indigenous peoples should be respected. It also presumes the right of Indigenous Peoples to continued existence within their national societies, to establish their own institutions and to determine the path of their own development.

Some of its most important provisions include:

Article 4: requires ratifying States to adopt special measures for safeguarding the persons, institutions, property, labour, cultures and environment of indigenous and tribal peoples

Article 5: establishes that, in applying the Convention, ratifying States must recognize and protect the social, cultural, religious and spiritual values of indigenous and tribal peoples, and respect the integrity of their values, practices and institutions

Article 6: requires, among other things, that ratifying States consult indigenous and tribal peoples through appropriate procedures, particularly through their representative institutions when legislative or administrative measures that may directly affect them are being considered, and provides that States should establish means for the peoples concerned to develop their own institutions

Article 7: establishes, among other things, the right of indigenous and tribal peoples to decide their own priorities for the process of development and to exercise control over their own economic, social and cultural development, and establishes the obligation of ratifying States to take measures to protect and preserve the environment of the territories inhabited by these peoples

Article 8: requires States to take indigenous and tribal custom and customary law into account when applying national laws and regulations to the peoples concerned

Article 13: requires governments to respect the special importance to the cultures and spiritual values of indigenous and tribal peoples of their relationship with the lands or territories that they occupy

Article 14: establishes that ratifying States shall recognize the rights of ownership and possession of the peoples concerned over the lands that they traditionally occupy, and that States shall establish adequate procedures within the national legal system to resolve land claims brought by indigenous and tribal peoples

Unlike The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which is a set of guidelines that Nation States can adopt in good faith, ILO Convention 169 is a legally-binding international agreement. For that reason, the Convention has been ratified by just 22 States (as of March 2012); but that number is still growing.

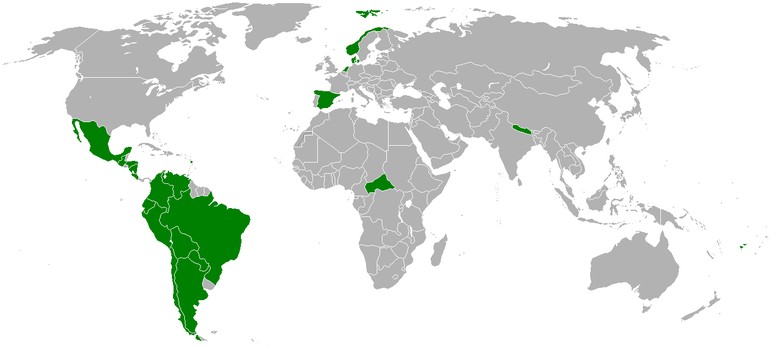

Map showing states that have signed and ratified the ILO-convention 169

States that have ratified the ILO-convention 169: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Central African Republic, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Denmark, Dominica, Ecuador, Fiji, Guatemala, Honduras, México, Nepal, Netherlands, Nicaragua, Norway, Paraguay, Peru, Spain, Venezuela

To learn more about ILO convention 169 visit PRO 169, the Programme to Promote ILO Convention No. 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples.

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.