Indigenous Peoples are environmental stewards of some 65 percent of the planet – despite making up just 6 percent of the world’s population – and some 95 percent of the world’s most threatened biodiverse regions. They are also experiencing the most advanced impacts of climate change. This makes Indigenous Peoples major stakeholders in the climate change debate.

Unfortunately, colonialism dies hard. Numerous structural inequalities prevent Indigenous Peoples from taking part in the climate change debate in a meaningful, democratic way. Instead, Indigenous Peoples are kept in the fringes as “Outside-Outsiders,” where they are denied access to delegates, blocked from contributing to negotiations and even excluded from outcome documents that have a direct impact on their lands, their livelihoods and their rights. To make matters even more complicated, Indigenous Peoples face another set of obstacles from lobby groups whose interests run counter to their own. As Tom Goldtooth explained in Part Two of our interview, Indigenous delegates may be “swarmed” to force that delegate to change his or her mind or to keep him or her from participating in a particular debate. There is also a wide use of divide and conquer tactics, ensuring that Indigenous Peoples have a minimal impact on international debate.

However, the situation is far from a lost cause. As we discuss with Tom Goldtooth in the third and final installment of this interview, Indigenous Peoples can strategize by taking advantage of opportunities to influence the outcomes of climate debates, and by utilizing the organizing power they have at home to ensure that states implement responsible climate change initiatives, laws and policies; especially if those states continue to deny them a right to deliberate at the international level.

Let’s talk about your success with non-civil society actors. Have you been able to speak with delegates from countries? Politicians? Or does everything happen through this backdoor channel of NGOs that you’ve been describing?

All of the above. There’s no one way, it’s a multi-pronged approach on the inside. Some of our delegates were accredited to go on the inside, and our tactics there are not just protesting and rallying. We use a number of tactics including scheduling press conferences and helping other indigenous groups to schedule press conferences. We have a media team. Media is very critical, so we’re able to schedule time to have press conferences for the caucus and for our own personal agenda around different issues. And then the caucus itself, with the participation of Alberto Salamando, for example, our legal advocate, and then the leadership that I know from throughout the years, are very good at lobbying strategies. There’s a number of different delegates there of indigenous peoples from different parts of the world. So, through the caucus we have a process of analyzing who we need to reach out to. Who has clout and power to support the rights language? And by the way, the REDD topic, the indigenous peoples who are pro-REDD, they understand now that the best scenario for them, if they’re supporting REDD, is to get their rights recognized. So that’s where we’ve been able to work with them and say, “well, at least let’s work together on strengthening rights.” At one point we suggested the narrative of “No rights, no REDD.” They need to do everything they can to get their land rights, their titles to land. Land titles are very important.

In Lima, [indigenous peoples] were pushing a legally binding agreement like Kyoto that had weight and meat to it, especially on the parts of the agreement that could recognize our rights. The recognition of the rights of indigenous peoples has always been a critical issue with us. Coming out of the many years of drafting the declaration, what we’re fighting for is our collective rights as peoples. That’s with an “s” on peoples. We’re not fighting for our individual human rights. Many of the NGOs that work on human rights are talking about the human rights of women, climate refugees, children, youth, etc. U.S. human rights are based upon individual human rights, but what we fought for are our collective rights, the “s” on peoples. And that was recognized in 2007 through the declaration that was adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations. Of course, the U.S., Canada, Australia, and New Zealand refused to adopt it.

Canada ratified the UNDRIP three days ago [May 10, 2016]. What is your opinion on that?

We’re cautious, because the important word to us is to adopt it “without qualification.” The minister of Indian Affairs representing Trudeau did say “without qualification.” But in her second breath, she said “in accordance with the Canadian Constitution.” So that’s going to be the problem. On the positive side of that, it does open the door for negotiations. But as we experienced with the US, it’s a question of whose terms. What are the terms of negotiation, and who defines those terms? In Canada, the Parliament gives money to the First Nation tribes in Canada. Any time tribes get radical and resistant to the Canadian federal government, they cut off their funding. There’s a long history of that. So some people are very cautious about their new direction.

Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Carolyn Bennett. Photo: Robert Thivierge / Wikipedia. Some Rights Reserved

There’s a lot of debate internally within indigenous peoples. One of the symptoms of colonization that we experience, along with Aboriginals, or the Adivasis from India, and many others, is internalized oppression. So we fight amongst ourselves. Sometimes governments can just sit back and let us go at it. There’s a lot of that in Canada. There’s an old term that came out of treaty-making times in the 1800s, it was brought up again in past decades: “hang-around-the-fort-Indians.” Forts went up, the more resistant tribes didn’t like settlers coming in, so they always resisted. Then there were the ones who said, “I want the best for my children, maybe these people are good. I’m going to hang around the fort.” So a lot of Indian people get handouts, they start to dress like the settlers, the white people, they cut their hair, they end up going to the church schools. And then there are the traditionalists, who say basically, “I’m going to keep on fighting, I’m going to wear my hair long. I’m going to wear my moccasins. I’m not going to sign no treaties.” So that kind of thing continues, even though that was back in the 1700s and 1800s. The pipeline resisters out of Sioux Country and the prairie lands come from that long lineage of resistors. Colonization in the U.S., Europe, the UK, Australia, New Zealand, they push that same phenomena in these climate negotiations. The World Bank does the same thing, especially on this issue of REDD. They divide and conquer.

Back to strategy: The caucuses were able to strategize, to get people to go and talk to a delegate from the country and try to get them to support one word, two words, or a sentence. So the caucus develops a lobbying text, which was done in Paris. And they share that lobbying text with NGOs, and say, this is what we’re fighting for, help us on this. All of the above, was tried in Paris. Who fought us? The United States was one of the ones fighting.

Right, they pushed for the text to be removed.

Yeah, and in Lima it was Japan that came in out of nowhere, against it. And then the UK stepped in. And there’s no indigenous peoples in the UK. We’re saying, “what the hell?” But that’s part of the strategy. The UK is invested in their colonization in India and in different parts of the world, so they have their own colonial perspectives, and in climate change, we’re talking about resources and we’re talking about market systems. So we’re talking about the privatization of nature. And the Prince [of Wales] has a handle on that. They’ve been participating in the privatization of land and trees and water and making money in the carbon market system. Those are some underlying things that we fight that the press usually doesn’t want to pick up.

What are the current obstacles within the United States for indigenous peoples who do not support REDD?

The biggest obstacle right now is getting the U.S. to really develop a climate policy of real solutions. Obama’s [Clean Power Plan] is not going to get the U.S. and the world to where we need to be, and we have to talk about emissions targets, reduction targets. The way that there’s a manipulation of numbers is something that we always recognize, and how historically the public of the United States has been left out of these negotiations. The market system is only one component, but it’s a major component. I always do say that of all the NGOs that are participating – and I can safely say, white NGOs – there are a few of them that really fully understand the market system, the market regimes, and those few are like EDF, for example, who’s invested in that. Domestically, NRDC. The other group is Conservation International. There are few that really understand it; the majority don’t. The Clean Power Plan incentivizes other forms of dirty energy. What it does is it shifts US energy policy towards nuclear power, towards mass incineration of biofuels and agrofuels. Here in Minnesota, we’re experiencing the state trying to include large hydrodams as clean energy, so that hyrdodams will meet the definition of clean energy standards so that the US will be able to fulfill their target reductions and look good on paper by including electricity from hydrodams. Here in Minnesota, I think it was about 14% [one source states 11%] of our energy comes from Manitoba hydro, which has actually flooded First Nation territories across the river. And then there’s Quebec hydro, and those have a history of devastating the tree lands, flooding them out. So these are different areas where we see false solutions in the US plan. There’s really no effort to cut CO2 emissions at the source. They’re greenwashing, they’re saying we’ve gone carbon neutral, and that doesn’t do much for the local low income people living in those areas, who are dying from respiratory illnesses. It requires a large scale popular education campaign of waking up Americans about the complexity of climate policy. And even when we do that, it just goes over people’s heads.

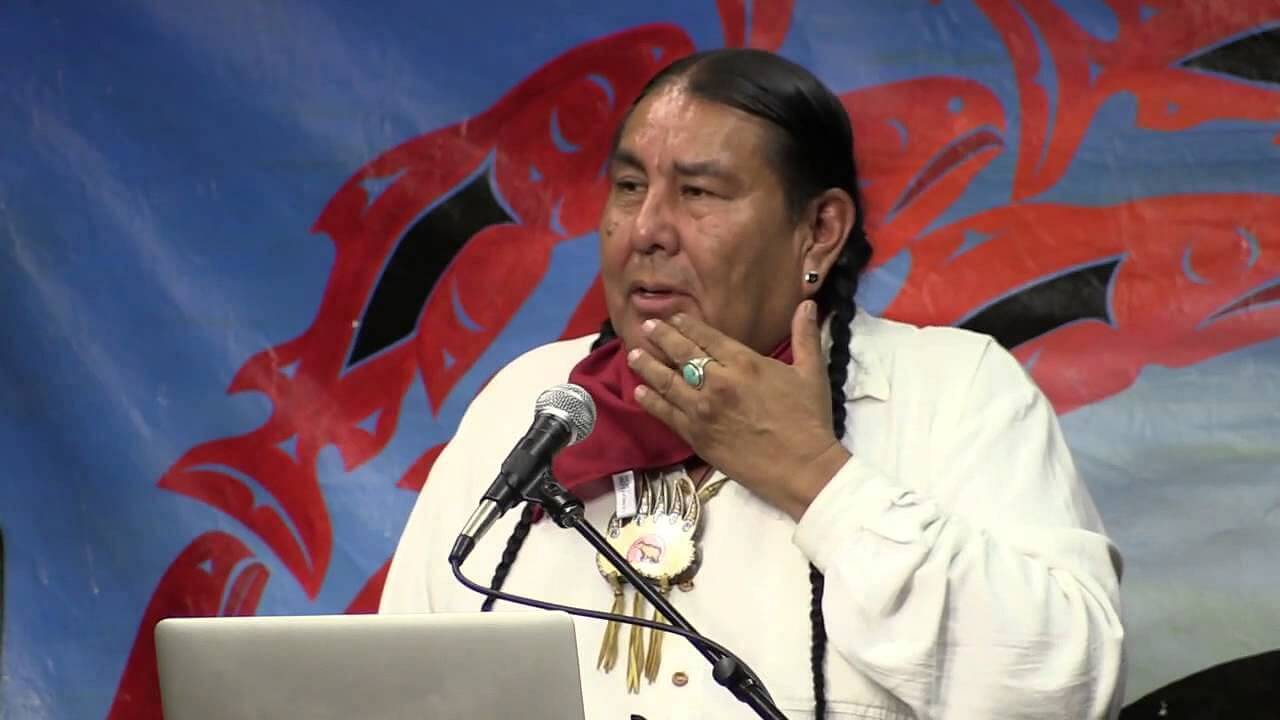

Photo: IEN

This interview with Tom Goldtooth reveals that the structural inequalities within the climate change debate are both complex and numerous, and that within the “Outside-Outisder” indigenous groups, some are more outside than others. Clearly, reforms are necessary in order to ensure that indigenous voices, and not only ones that support REDD, are heard. Part of this includes funding for Indigenous Peoples who do not support REDD. But the United Nations needs to ensure that the rules are fair within conferences as well. Meetings should be sponsored by the UN to ensure that politics are not being played in exclusive settings where NGOs with corporate agendas call the shots. Those who do engage in divide and conquer tactics should continue to be called out openly in the media. Equal access should be provided to conferences where policies are debated and shaped before being brought to the international negotiating table. Additional research on this exclusive game playing and these divide and conquer strategies are necessary, as well as working with states to ensure that indigenous voices are included in crafting climate change policies at the domestic level. Finally, it is essential that Indigenous Peoples are able to access and shape climate change debate outside of the international policy-making domain. By engaging with the public, Indigenous Peoples can ensure that these issues are argued out and that they can incentivize further activism and pressure for change.

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.