Venezuela is set to hand over 12% of the nation’s territory in the upper reaches of the Amazon rainforest to mining corporations, writes Lucio Marcello, with 150 companies from 35 countries poised to devastate the army-controlled ‘special economic zone’. But resistance is growing, and a counter-proposal aims to protect the area’s precious biodiversity, indigenous cultures and water resources in a new South Orinoco Mega Reserve.

On 24th February 2016, with no debate within Parliament or civil society, the Venezuelan government decreed that the upper reaches of the Amazon Rainforest, amounting to 12% of the country’s landmass, were to become a Special Economic Zone devoted to mining gold, diamonds, coltan, iron and bauxite.

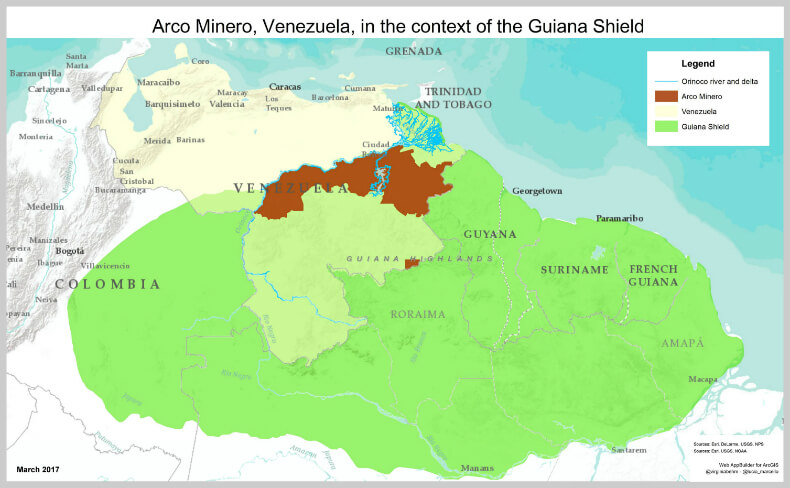

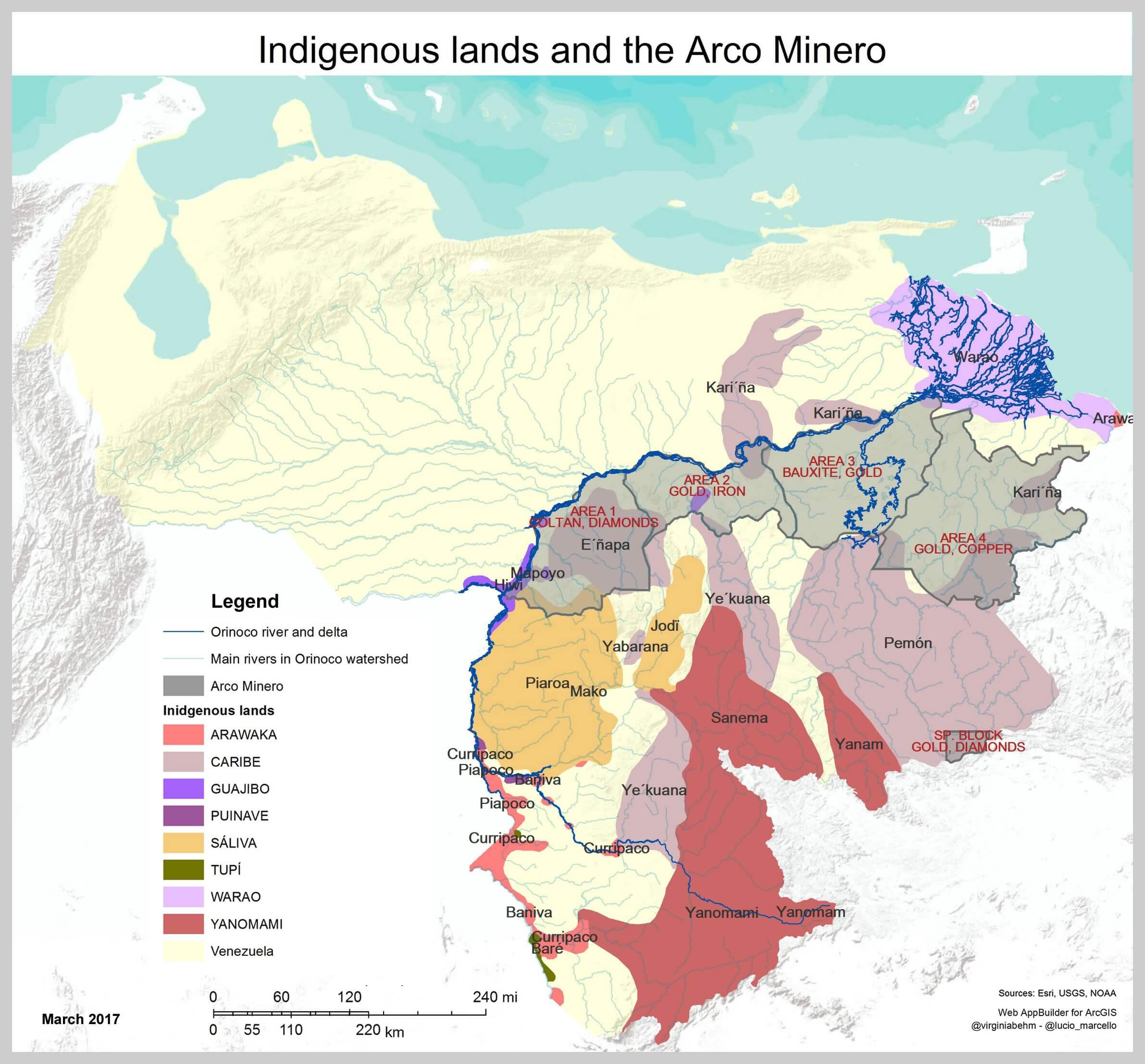

The name chosen for the new zone was the ‘Arco Minero del Orinoco’ (Orinoco Mining Arc), after the arc-shape made by the course of the Orinoco, Venezuela’s main river. The zone is now under military control, and constitutional rights have been restricted.

The area also happens to constitute a significant portion of the Guiana shield, a very ancient mineral-rich geological formation spanning Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana and Brazil, which is facing increasing threats from both small and large-scale mining operations.

Rising opposition to the Arco Minero

Concerted legal action was taken on 31st May 2016 by former ministers to request that the supreme court revoke the creation of the Arco Minero, and a broad civil society movement came together in July 2016 to form the ‘Plataforma por la Nulidad del decreto del Arco Minero del Orinoco’ (Platform for the Annulment of the Orinoco Mining Arc decree).

Those opposing the decree consider it to be unconstitutional and in breach of several laws protecting the land rights of indigenous people and existing natural reserves against mining.

On 27th November, the Supreme Court dismissed the appeal on grounds of violation of the constitution (writ of amparo) as baseless, given the ‘strategic importance’ of mining for the country. Nevertheless, the legal action continues.

On 2nd December 2016, three Venezuelan NGOs (Provea, Laboratorio de Paz and GTAI-Ula) addressed the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) to denounce that indigenous people had not given free prior and informed consent to the Arco Minero.

Government representatives had to admit that no environmental impact assessment had been undertaken, while claiming support from indigenous people, whose rights to free association have been curtailed and funnelled towards governmental organisations with limited grassroots support (Laboratorio de Paz investigation, 2014).

IACHR should issue a report and recommendations imminently (within three month of the hearing).

Venezuela’s systemic crisis

Venezuela is in the midst of a deep systemic crisis, with widespread hunger, very limited access to medicines and healthcare, and escalating violence and human rights abuses permeating all aspects of society. Its oil-dependent economy has been suffering since oil prices started falling in 2014.

The country plunged into a downward spiral, both spurred and worsened by widespread corruption and the mismanagement of existing resources and productive activities: over the years, the wealth derived from oil was not reinvested, but rather spent on imports or squandered; not only were many fields left untilled, the very oil extracting facilities upon which the entire economy depended had not been maintained.

Venezuela intends to use the revenue generated by mining to get out of the country’s crisis, but at what cost? Many people describe the operation as bringing ‘pan para hoy y hambre para mañana’ (bread today and hunger tomorrow).

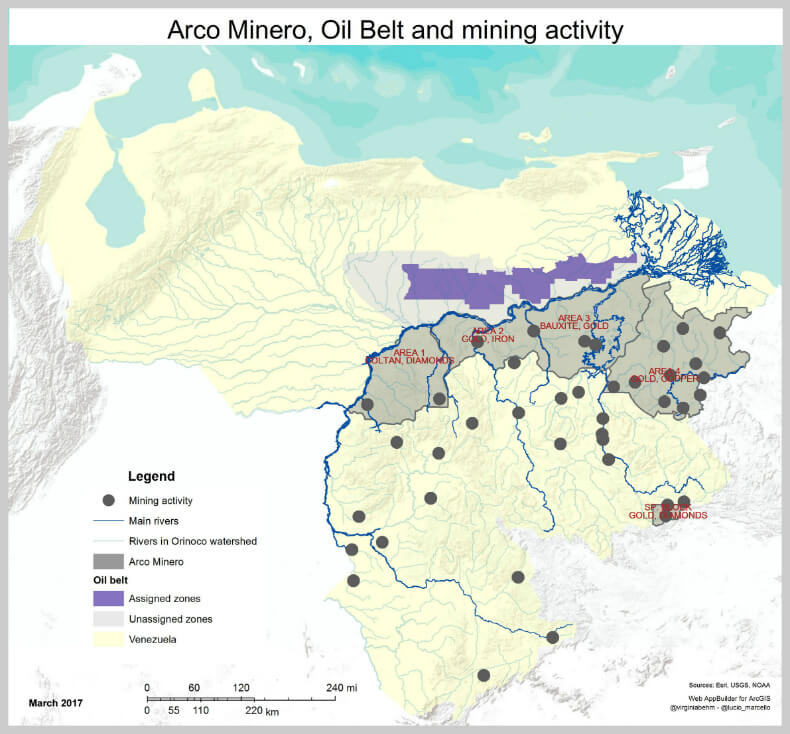

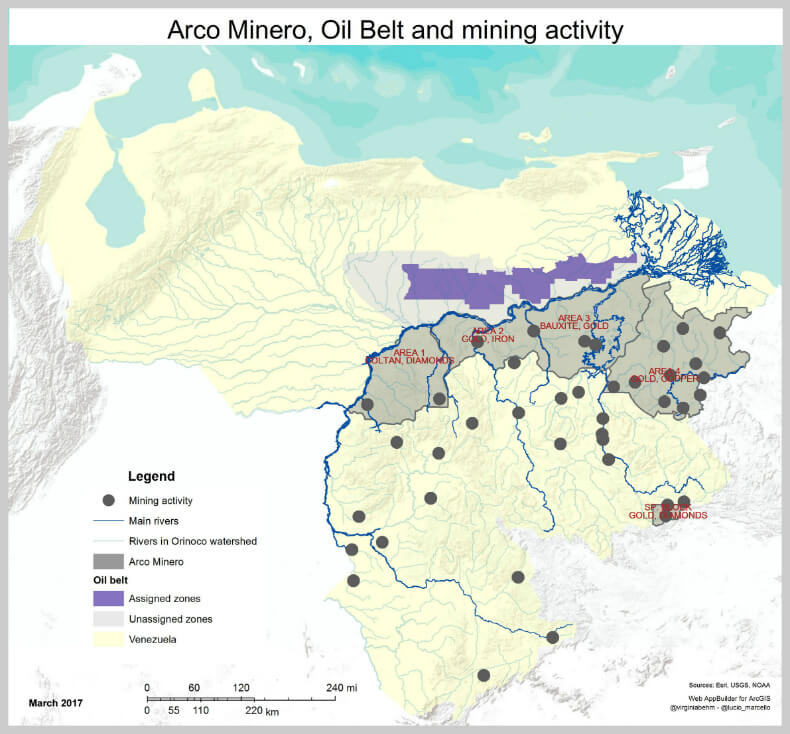

The Arco Minero also goes hand in hand with exploitation of the Orinoco Oil Belt (Faja Petrolifera del Orinoco), immediately north of the Orinoco river, the largest extra-heavy oil deposits in the world, in the form of tar sands whose characteristics and potential impact on the environment are directly comparable to the tar sands of Alberta in Canada.

Restructuring the economy in a sustainable manner and taking measures to address the severe problems at hand without perpetuating a rentier state model, whether based on oil or mining, is actually a viable alternative.

Although Venezuela’s interest in renewables is currently low (tellingly, Venezuela has yet to ratify the Paris Climate Change agreement), the country’s wind and solar power potential is huge. Tourism could be another great asset to the country, as long the county’s natural environment is preserved.

Unfortunately, the rentier model and widespread corruption seem to have been the driving forces of what has been described as a severe man-made crisis, and the mind-set behind a very disconcerting set of solutions.

Guayana: what are its real assets?

The Arco Minero (111,843.70 km2) corresponds to 24% of Guayana, the region within Venezuela south of the river Orinoco (458,344 km2), comprising the states of Amazonas, Bolivar and Delta Amacuro.

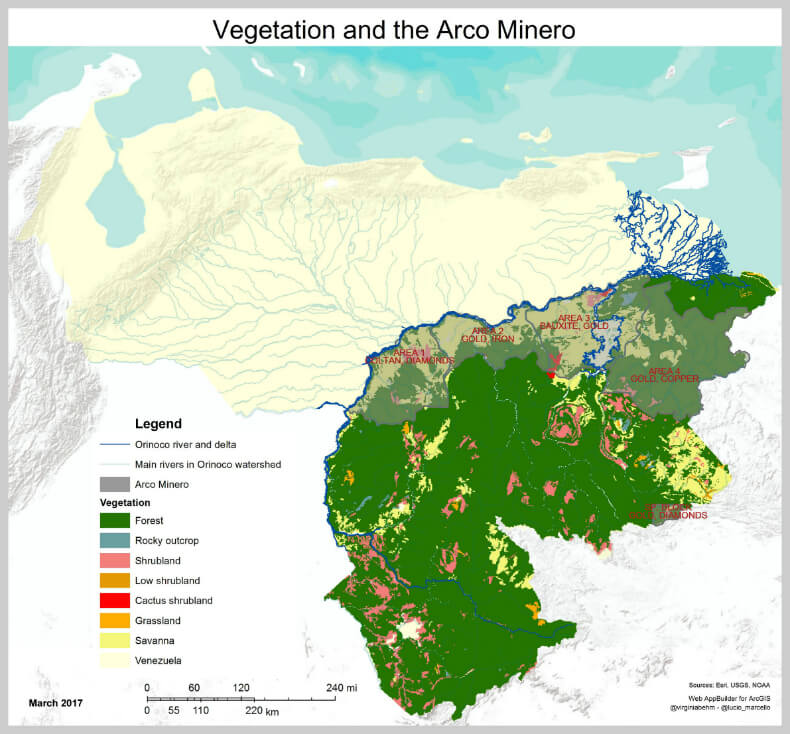

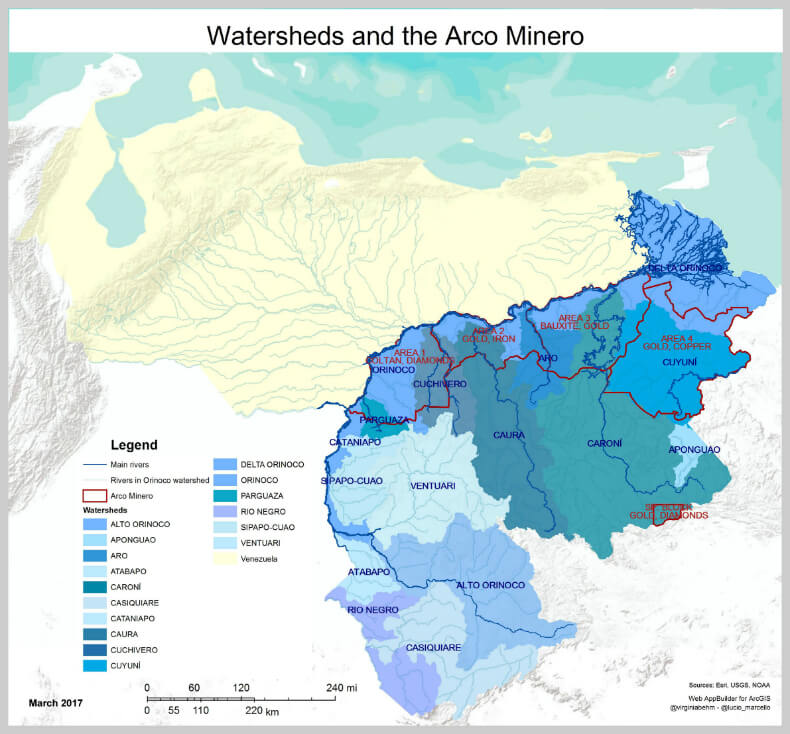

Guayana constitutes the upper reaches of the Amazon rainforest, and is of outstanding natural importance: it holds 60% of the country’s freshwater resources and 50% of its animal biodiversity. The Arco Minero is mostly forested (64%), with rainforests, primarily found in Area 4. amounting to over a third of forested areas.

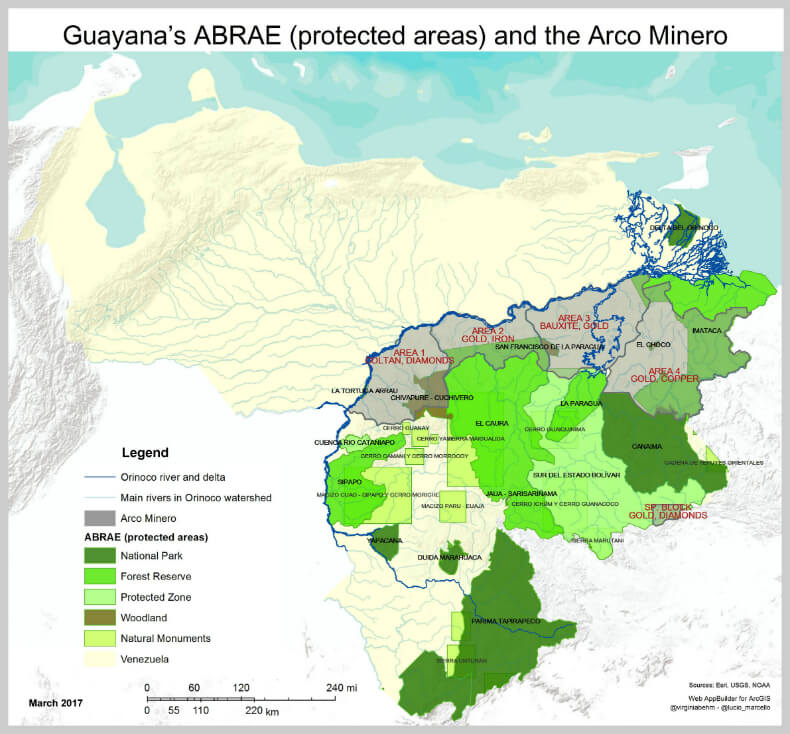

A number of Natural Reserves and National Parks collectively referred to as ABRAE (Áreas Bajo Régimen de Administración Especial – Areas under Special Administration) protect ~70% of Guayana from mining and other forms of environmental degradation, but protection measures are not always enforced effectively.

Immediately south of the Arco Minero lies Canaima National Park, a Unesco world heritage site, now threatened by encroaching mining operations (550 / 30,000 km2 are already affected, according to RAISG, the Red Amazónica De Información Socioambiental Georreferenciada).

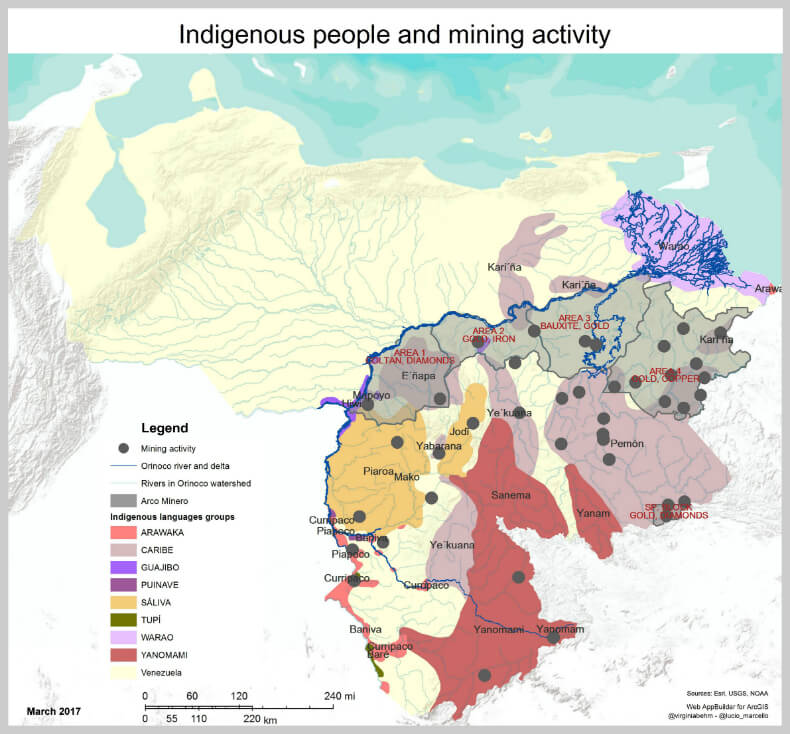

Guayana is also the home of 19 indigenous peoples, whose way of life is in principle safeguarded by Venezuela’s 1999 constitution. Even though only 12% of their lands have been demarcated, around two thirds of these are located within ABRAE, conferring some degree of protection, at least on paper. As many as 11 different peoples (Pemon, Yekuana, Karina, Enepa, Mapoyo, Arawak, Piaroa, Sanema, Akawayo, Jodi/Hoti and Pume) are directly affected by the Arco Minero.

Climate change and drought are already taking their toll on Venezuela: water scarcity has a direct effect on the generation of electricity, as 60% of the country’s electricity is generated by a set of four dams along the Caroni river (the major tributary of the Orinoco), whose flow in recent years has been severely affected by droughts, to the point that the government has had to ration electricity several times over the past years.

Now more than ever it would seem critical to maintain tree cover and an intact rainforest ecosystem.

Guayana has been purported to hold the second largest gold reserve in the world, estimated at 7,000 tonnes, worth some $200 billion dollars. Gold is not a recent discovery though, as the area has long been taken over by illegal mining operations.

In recent years, as many as 70,000 impoverished Venezuelans have left their homes to make a living in illegal mines and some estimates suggest that a total of 150,000 illegal miners (including Colombians and Brazilians) are operating across the entire region.

Living conditions are difficult, worsened by a severe malaria epidemic originating around mining sites, as tree cover is replaced with stagnant water pools, the perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes. The entire area is managed by criminal organisations, and mining is affecting local communities and indigenous people in particular, leading to social erosion and to a drastic increase in prostitution, as ‘wealth’ is generated in the mines.

According to another RAISG report, mining is already the main driver of deforestation in Guayana, Venezuela being the only country where Amazon rainforest deforestation rates increased between 2000 and 2013.

Arco Minero Plans (the Motor Minero)

In the government’s view, Arco Minero plans are also in place to put an end to illegal mining, and the authorities claim that mining operations will be restricted to those areas already affected by illegal mining within the Arc, rather than the entire Arc.

While illegal mining is recognised by all parties as a serious issue, the government’s solution to have more mining is at odds with the ecosystem services provided by the rainforest and with the lives of indigenous people.

As mentioned above, mining is currently not restricted to the Arco Minero: significant illegal mining operations are conducted across the rest of Guayana, and these are likely to continue undisturbed.

A confirmation of this can be seen in recent reports suggesting an increase in illegal mining in areas where operations can be only equipped and fuelled by rivers passing through the Arco Minero, suggesting that no effective measures have been put in place over the past year to curb this practice.

Within Venezuela, the operation has been widely described as an ‘ecocide’ and a ‘silent genocide’, as it would result in habitat degradation, forced relocation and urbanisation of traditional communities.

Gregorio Mirabal, leader of Venezuela’s non-governmental indigenous organisation ORPIA (Organización Regional de Pueblos Indígenas del Amazonas) has clearly stated the indigenous people’s opposition to the Arco Minero, also voiced by many other indigenous organisations.

Furthermore, there is precedent for mining companies to start with a relatively small and defined project and then expand following the results of explorations in surrounding areas. The recent case of Belo Sun mining in Brazil is emblematic: after a localised site downstream of the Belo Monte Dam, the company is now interested in a 120 km ‘strike’ of gold within a greenstone belt.

The interests at stake are huge, as gold is only one of the several minerals the region abounds with, which include diamonds, coltan, copper, iron and bauxite. As many as 150 corporations from 35 different countries have been enlisted in the project, though only a few names have so far been revealed.

These include Gold Reserve, Barrick Gold and Energold from Canada (gold), CAMC Engineering Co. and Yankuang Group from China (coltan and gold respectively), Afridiam from DR Congo (diamonds, gold and coltan), Bedeschi from Italy and Guaniamo Mining Company from the USA.

Coltan is particularly important for its strategic role in electronics and in the military sector, and has been the first industrial-scale mining operation to get the green light, with projected reserves worth $100 billion.

The newly-approved coltan mines are located in Area 1 close to where the Parguaza river meets the Orinoco, at the border with Colombia, where 10,000 hectares inhabited by the Piaroa indigenous people have been granted for 20 years to a new entity named ‘Parguaza corporation’.

The decision was taken in spite of Piaroa opposition (and with bribery attempts), and also in the absence of a mining plan, let alone an environmental assessment.

Environmental impacts

Gold mining comes with huge environmental risks: aside from deforestation, habitat fragmentation and the impact on local communities through forced processes of ‘modernisation’, it also causes significant pollution.

Though development of the Arco Minero might not include the use of mercury (which has caused and is still causing widespread water pollution across the entire Amazon basin), toxic waste generated by modern mining includes water contaminated with cyanide, which is stored in large tailings dams.

The Venezuelan government promises that the Arco Minero will be a model ‘clean’ and ‘eco-socialist’ mining project. However, even in state-of-the-art mining operations, tailing dams are prone to leaking and contamination of waterways. Just over the last year, two cyanide spills occurred at Barrick Gold’s mega-mines in Argentina, and the company was forced to suspend operations temporarily.

In addition, given the large volume of earth needed to extract 1 gram of gold (estimates are 1-1.5 tons of earth), the waste generated is enormous, and the area used for extraction is essentially dead thereafter, with little chance of it ever being recovered for other uses.

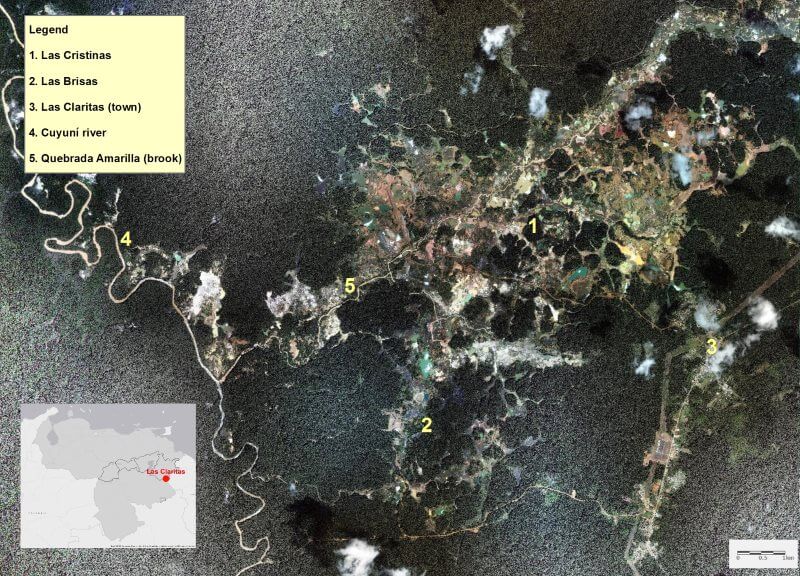

In Venezuela, large-scale gold mining is not an absolute novelty, it has already left deep scars at Las Cristinas and Las Brisas mining sites (see satellite image).

Satellite image: the scars of mining at Las Claritas and Las Brisas.

An alternative vision: the South Orinoco Mega-Reserve

Former senator Alexander Luzardo, co-author of the environmental section of Venezuela’s constitution, has put together a counter-plan to the Mining Arc, demanding the Arco Minero project to be scrapped and strengthening and extending the protected status of the regions south of the Orinoco River.

This has now become a law proposal under the name of ‘Mega Reserva del Sur del Orinoco’, the South Orinoco Mega-Reserve, and has been championed by Americo De Grazia, an opposition leader working within the Arco Minero parliamentary sub commission. It envisages a complete ban of mining, the protection of indigenous peoples, of the Orinoco river basin and of the rainforest at large, and the promotion of tourism and sustainability.

The proposal is currently being discussed by Venezuela’s National Assembly, where the majority is held by a coalition opposing the Maduro government, responsible for launching the Arco Minero project.

Why now?

Plans for the Arco Minero were first outlined by President Chavez in 2010, spurred by a spell of low oil prices and by geological surveys started in 2006 that led to the discovery of significant coltan deposits.

The plans mark a U-turn from Chavez’s previous climate change-conscious sustainable development intents. Venezuela’s current crisis seems to have come as the perfect opportunity to move forward with the project ‘for the public good’.

The government’s lack of transparency and clampdown on media, combined with the military hold over the Arco Minero, means that information is filtering through in tiny propaganda snippets (for example the celebration of the Mining Arc’s first ‘clean’ gold bar), stifling the opportunities for real debate.

More journalistic investigations and coverage on Venezuelan and international media are warranted to expose this potentially catastrophic operation and to lend strength to the alternative plans put forward by the large number of people and organisations wanting Venezuela to protect its already fragile rainforests.

Lucio Marcello is a molecular ecologist with a background in tropical disease research. He currently works as a researcher at the Rivers and Lochs Institute in Inverness, Scotland. He has been campaigning on rainforest issues since 2010, as part of the global movement arising in opposition to the plans to build the Belo Monte dam in Brazil.

In April 2016, he founded Listen to the Amazon, an organisation aimed at promoting awareness of the threats faced by the rainforests of Latin America, and of the actions taken by environmental defenders to protect forest communities and their lands, with particular focus on issues that might not receive much coverage in the media, such as the Arco Minero in Venezuela. He tweets @totheamazon.

Listen to the Amazon is part of the Yes to Life No to Mining network.

Acknowledgements

The maps featured in the article were derived from the Arco Minero Story Map, an ArcGIS interactive Story Map developed in collaboration with Virginia Behm (@virginiabehm), a geographer with extensive expertise in cartography and direct knowledge of the Venezuelan Guayana.

Key links

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.