“In my song you hear my soul, in my dance, you see its rhythm.”

~ Basil Johnson

On November 22, I was part of a halftime dance performance at the TCF Bank Stadium where the Minnesota Vikings celebrated Native American Heritage Month. The program included a pregame show with a presentation of 27 tribal nation flags from Minnesota and Wisconsin, the Lakota Warrior Women’s color guard with service flags, and the national anthem by Rep. Peggy Flanagan of the White Earth Ojibwe Nation.

The halftime show was the main feature. Under a dark sky with a temperature of 25 degrees, twenty-one dancers danced to the songs of the RedBone Singers, a Twin Cities based drum group. Six dance categories were represented – men’s traditional, women’s traditional, grass dance, jingle dress, fancy shawl, and fancy feather. To the rhythm of a grand entry song, the dancers formed a circle at the center of the field around the Vikings logo, and performed break dances with songs appropriate for each category.

It was only a six and half minute performance, but it left an indelible impression on the dancers, singers, and crowd of 52,000 fans. The official halftime video has been viewed by over 407K people on the Internet.

For me, it was the high point of my life as a dancer. I not only represented myself, but also my family, clan, tribe, and Native peoples across Turtle Island.

Most importantly, for the dancers and singers, it was the opportunity to counter the stereotypes epitomized by the Washington Redskins. It completed a circle in a city that has protested and marched against the Washington team in 1992, 2013, and 2014.

RedBone Singers and Dancers

Dance has been an integral part of indigenous cultures long before colonialization. In my culture, there are traditional stories regarding the origins of dance. In the story of Anishinaabe (Original Man), on the day of his creation, he rose up and took two steps with his left foot, then two steps with his right foot. Those steps became the steps used in dance. There was Papeekawis who gave dances to the Anishinaabeg and instilled in them a love for dancing. Lastly, there was Chibiabos who brought songs to the Anishinaabeg and taught them that music was the language of the soul.

Dance was deeply ingrained in the traditional life of the Anishinaabeg. Basil Johnson writes: “These performances [were] more like ballet in style and purpose than ordinary dances. The performances [were] meant to dramatize some event, happening, story, or even dream.”

Among the Anishinaabeg, certain dances engaged the entire community. The Scalp Dance was part of the dance complex generally referred to as Nandobaniishimowin, or the War Dance. The name was derived from the term Nandobaniiwin, meaning warfare. The Nandobaniishimowin dance complex consisted of several interconnected dances. Ogichidaag (Warriors) participated in certain dances that were a part of the complex. The Scalp Dance involved the community and was intended to honor the lives of those taken.

The beginning of the contemporary powwow can be traced back to the Hethushka that developed among Omaha and Ponca warrior societies in the early 1820s. By the mid-1800s, the Hethushka dance developed as a non-secular version of the war dance. The Hethushka were basically drum and dance societies, each with their own songs, singers, and dancers. Hethushka dancers wore their warrior regalia, including roaches, scalps of opponents represented by braids of sweet grass, eagle bone whistles, and feather belts or bustles. The Yankton Lakota adopted the Hethushka and called it the Omaha Dance, or Grass Dance, the latter in reference to the braided sweet grass worn at the belt.

By the 1860s, the Dakota brought the Omaha Dance into Anishinaabeg country where it was referred to as the Sioux Dance.

In the early 1900s, the powwow began to take shape and form. The Omaha/Sioux Dance divided into two distinct dance styles – men’s traditional and grass dance (non-bustled dancers). Among the Anishinaabe, a new dance style emerged for women – ziibaaska`iganagooday, the jingle dress.

By the 1960s, the transitional periods of dance emerged into the contemporary powwow of today with its various dance categories and attendant regalia. Although the powwow may be labeled as contemporary, it isn’t new. Native dance has always been a part of the community infrastructure.

In short, dance has a deep and rich history among tribal peoples. Dancing was, and continues to be, a fundamental expression of heritage and identity.

I can only write about dance from my own perspective, my own experiences, and my own history as a dancer. As a young boy, I attended the annual powwows held at Red Lake. Like most Red Lake families, we went to powwows as spectators. But that didn’t prevent me from dancing. I loved going out dancing in my street clothes, sitting on the wood benches around the arbor, listening to the old men at their drums, and looking at all the beautiful dancers in their colorful regalia. Someday I knew I would be a dancer.

That day came many years later, when I was in my mid-30s. I had stopped drinking and a few months into my sobriety, I had a powerful, lucid dream-vision. I went to an elder, gave him asemaa (tobacco), told him of my dream, and he said that the manidoog (spirits) were telling me to dance. In becoming a dancer, I not only fulfilled my dream-vision, but it also gave me a base of support for my sobriety. Most importantly, dance became a way to decolonize my identity that had been subjugated by the boarding schools my parents and grandparents were forced to attend. For me, dance was part of a healing journey that was part mental, emotional, physical, and spiritual.

As a dancer, I’ve participated in contests and traditional powwows. And I’ve been a part of dance exhibitions in schools. Exhibitions and lectures have played an important role in that they have allowed me to educate about dance and its meaning to Native people.

However, dance, like so many other things that are Native, has been appropriated and commodified by dominant society. Although its appropriation has, by no means, replaced Native American dance itself, it has provided a representative of dance that distorts and misinforms a tribal reality.

The Koshare Indian Dancers epitomize the appropriation of Native American dance in mainstream society. The Koshare Indian Dancers are the members of Boy Scout Troop 232 and Venturing Crew 2230 of the Rocky Mountain Council. They originated in 1933 at La Junta, Colorado.

According to their literature, new members are called Papooses, and begin their Koshare career by working on their Scout activities. Only when they have progressed about halfway up the Eagle Trail can they become Koshares. When a Scout has attained the rank of Star Scout, he must complete additional requirements to be elected as a Brave in the Koshare Indian Dancers:

To become a Chief in the Koshare Indian Dancers, a boy must first become an Eagle Scout. In its organizational structure, there is a head chief and assistant head chief; it is further divided into clans – Navajo Clan, Sioux Clan, and Kiowa Clan. Each clan has a chief. Beginning in 1993, two girls were added to make the performance more accurate in representing male and female dancers. In 2003, a Maiden program was formally created that allowed girls to participate in dance performances.

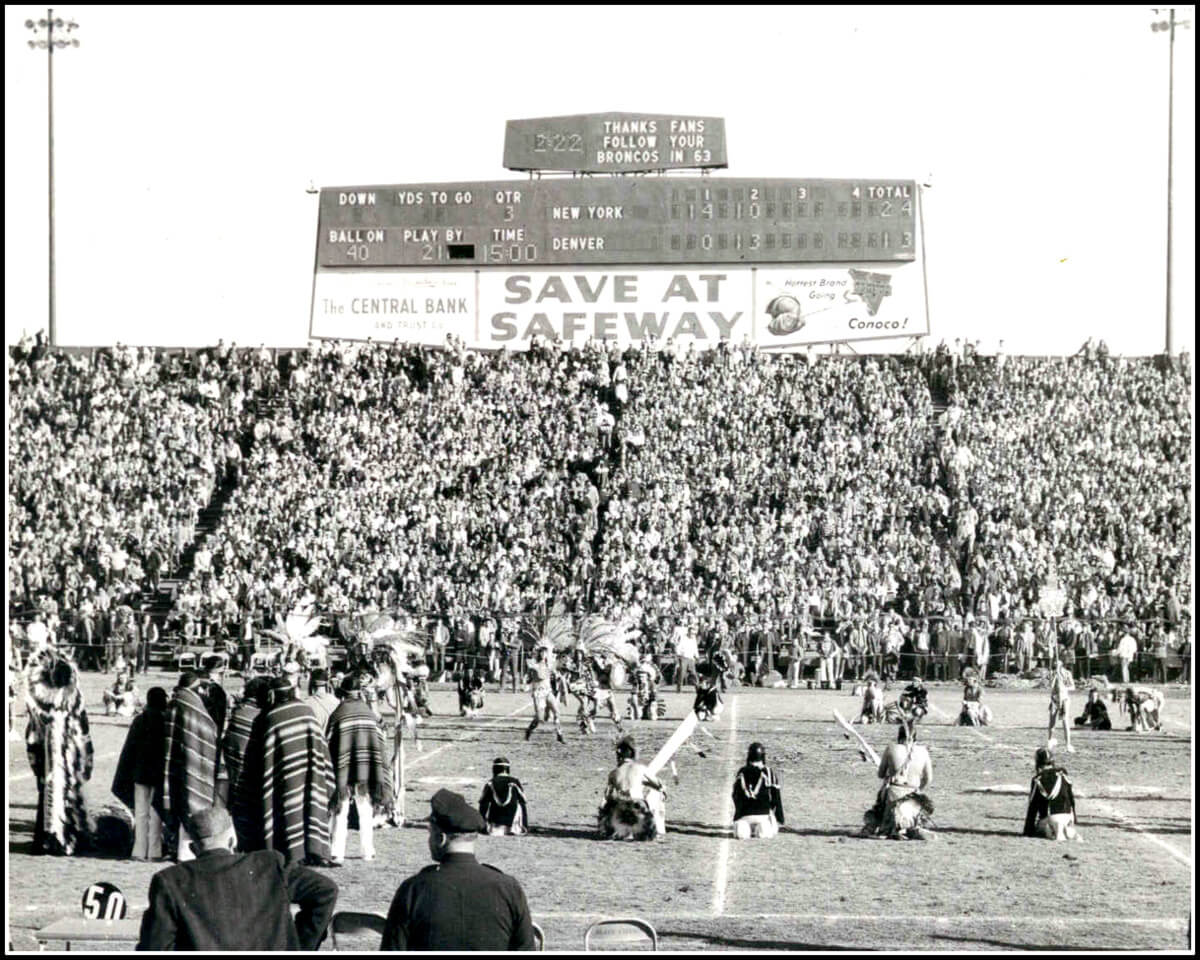

In their 83-year history, the Koshare Indian Dancers have received worldwide recognition. Their performances include Japan and England, and large sports venues including the halftime show between the Denver Broncos and New York Jets in 1962.

Koshare Indian Dancers, Halftime Show, 1962

The Koshare program developed during the time of the “Vanishing Indian.” Through treaties and allotment, tribal lands diminished to mere parcels of checker-boarded land. Tribal economies were basically non-existent. Traditional councils were overshadowed by progressive tribal entities that would become formalized under the Indian Reorganization Act in 1936.

Powwows were common events on many reservations and were attractions for tourists. For non-Natives, powwows were a vestige of a tribal past. It was the opportunity to see firsthand what many thought was the remnants of the Vanishing Indian.

It was against this backdrop that J.R. “Buck” Burshears founded the Koshare dancers in 1933. In September, the Koshares issued their first press release:

Scouts of Troop 230 met last evening and perfected a formal organization of the Indian club, which will be known as the Koshare club. Membership is limited to first-class scouts. The objectives will be to study Anthropology and Indian lore. It is hoped that they will be able to make public appearances within the next few months.

Two months later, the La Junta Daily Democrat covered the Koshare performance at an Elk’s Lodge:

A band of yelling, whooping, painted and be feathered Indians raided the Elks club last night, carrying off the figurative scalp of every member of the organization present.

Dressed in turkey feather or porcupine and deer head- dresses, wearing leather chaps, and stripped to the waist, the band of 18 warriors, led by heap big chief Francis Burshears rushed into the lodge room and captured the attention and applause of more than twice their number.

“The Indians” were members of Boy Scout Troop 230 and of the Koshara (note spelling) club which grew out of that organization. Beginning with the Sioux peace-pipe ceremony, the boys ranged themselves in a circle about the skull of a buffalo. Then came a hair raising Ojibway scalp dance, the Sioux circle dance, the sage chicken hop, the toe-heel step — all intricate and strenuous.

Featured was the Eagle dance which depicted an eagle caught in a trap. Vernon Elder showed excellent understanding of the pantomime, the great wings he carried circling nearer and nearer the imaginary trap until with a scream he was caught.

Starting with practically nothing, the Koshara club has built up its stock of costumes until today they are worth about $5,000 according to Burshears. Most of the work has been done by the boys themselves, even to dyeing the feathers and the stringing of their beads.

Koshare Dancers, 1937

Within the myth of the Vanishing Indian, the Koshare program emerged and objectified Native American dance into a dance pageant that, to this day, lacks form and meaning. Their dance outfits are costumes that are without cultural context. Koshare dance steps lack the rhythm of Native dance. Their repertoire includes dances from the Sioux, Kiowa, Ojibwe, Blackfoot, Navajo, Comanche, and Hopi. Specific dances include the ghost dance, eagle dance, deer dance, butterfly dance, and chief’s dance. Additionally, their Summer and Winter Ceremonials feature dances of the Pueblos of the Southwest.

The Koshare program has served as a model of cultural appropriation for other Boy Scout dance groups. These groups include the Kwahadi Dancers – Venture Crew 9, Aabikta Indian Dancers, Coyote Night Dancers, Kaniengehaga Dance Team, Kootaga Indian Dancers, Inc., Kossa Indian Dancers, Crew 476 Lakota Dancers, Paumanauke Dance Team, Sahawe Indian Dancers, The Mic-O-Say Dancers, Tsoyaha Indian Dancers / Mossy Creek.

The stereotypes that mark the Koshare dancers are not any different than professional models in headdresses, logos and mascots of professional sports teams like the Washington team, or Disney’s Peter Pan Indians. Their program has taken a culturally significant aesthetic and turned it into a pantomime that lacks the meaning and connections that are deeply rooted in the collective psyche of Native Americans. It represents the dark side of colonialism that, by its nature, subjugates the things that culturally diverse people value, and turns them into a commodity that they can profit from.

Koshare Indian Dancers

The Koshare program relies on corporate funding and grants, and individual membership donations for their activities and for their museum. The money from grants and donations commodifies the Koshare program and institutionalizes it as a stereotypical tribal reality. Not surprising in a state that forced out the Cheyenne and Arapaho Nations in its greedy quest for gold, that led to a notorious act of genocide – the Sand Creek Massacre. Indeed, the Koshare halftime show at Mile High Stadium in 1962, was not a celebration of Native life; rather, it was a celebration of cultural appropriation.

The Koshare group is no stranger to controversy. Several articles have been written regarding the Koshare dancers and their violation of cultural property that is central to the tribal ceremonial practices of the Tewa.

Patrick Victor Naranjo writes: “Cultural properties and the traditional knowledge associated with these indigenous identities are not relevant to the dominant perception of American Indians, as represented by the Cleveland Indian mascot and Koshare dance performance. While it is critical for tribes to incorporate an authentic indigenous aesthetic into dominant perception, indigenous identities should not simply be appropriated by a student group.”[1]

Naranjo suggests that tribal governments, under the rule of sovereignty, enact legislation to protect cultural property, in this case, Tewa cultural property. Such laws would have limited application since they could only be applied within the tribal domain; but they would give a tribe the power to issue resolutions that strongly condemn specific acts of appropriation.

The Koshare’s appropriation extends far beyond Tewa cultural property. Their cultural appropriation includes Native American dance itself and exploits the cultural property of several tribes including the Ojibwe, Lakota, Blackfoot, Kiowa, and Comanche.

Because the concept of the Koshare Dancers is so deeply embedded in the settler mindset, it will be difficult to eradicate. We can only expose it for what it is. Local Native groups can organize marches and rallies wherever the Koshare group performs. And social media can be used to apply pressure to expose flagrant acts of appropriation.

One thing is certain. The Boy Scouts of America are sensitive to public controversy. Sex abuse cases have led to multi-million dollar lawsuits. Litigation regarding homosexuals has led to lifting the ban against homosexuals.

Pressure from Native American organizations could very well lead to changes to subdue Koshare cultural appropriation. What is required is concerted effort to bring about that change and, in the effort, decolonize ourselves from the distortions of the settler mindset.

On a cold football field in November, people forgot about the stereotypes found in dominant society. In a brief moment in time, they witnessed the beauty of Native American dance. For the dancers and singers, it was a memorable moment of pride, grace, and dignity. And that’s the way it should be.

Photo by Miziway Migizi DesJarlait

Robert DesJarlait is an environmental activist, writer, artist, and dancer. He is from the Red Lake Ojibwe Nation and belongs to the Bear Clan.

[1] “A Lesson from the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 about Cultural Appropriation and Tribal Sovereignty: What Santa Clara Pueblo Can Do to Protect Tewa Cultural Property,” 2012.

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.