The Hawaiian language revitalization movement had humble beginnings: a dying language, native speakers who didn’t recognize the urgency, and next to no funding. But what the movement lacked in funding resources or stature, a committed circle of academics offered in a combination of vision and commitment that silenced their critics and established a legacy. Today ha’aha’a, or “humility,” remains a fundamental lesson to students at Hawaiian immersion schools, while the availability of Preschool – PhD education exclusively in Hawaiian is held up as a model for native language revitalization around the globe.

William “Pila” Wilson was part of the early cohort of academics in the seventies and has, in every sense of the phrase, walked the talk, from raising his children in an exclusively Hawaiian-speaking household, to building the ʻAha Pūnana Leo or “nest of voices” immersion school system. Pila has educated government leaders about the return on investment that supporting native language immersion has demonstrated (both raising graduation rates and lowering suicide rates) in some of the most remote areas with limited resources.

As a Native Hawaiian with a strong interest in evidence-based policy making, I’ve been amazed by the data on native language immersion and student success. With a desire to understand the why and the how, I asked Pila to explain the connection between native language learning student outcomes.

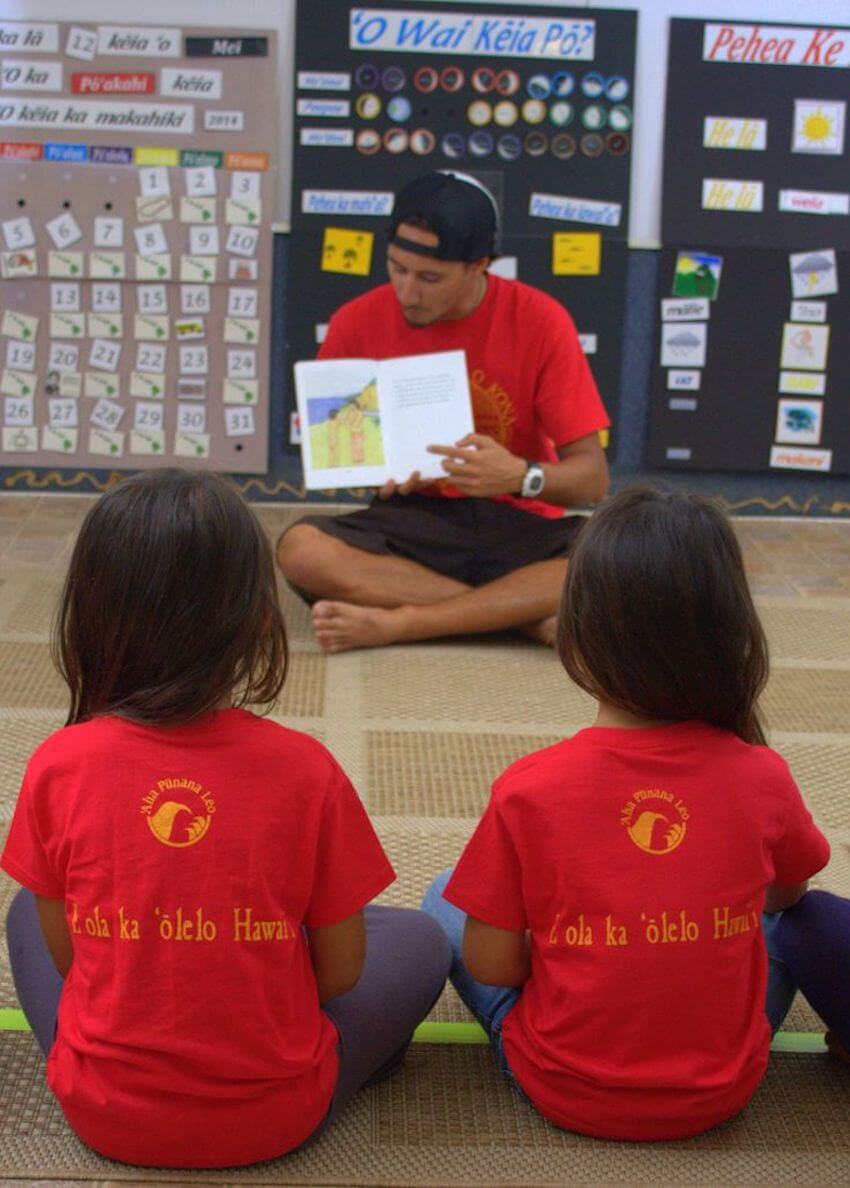

Young learners at ʻAha Pūnana Leo. Photo: ʻAha Pūnana Leo

Pila broadened my understanding of language from only the spoken and written word to include behavior as well as “how you hold yourself; treat others. How you act.” So that in the learning of the Hawaiian language, the curriculum in immersion schools weaves in cultural norms such as expressing respect and deference to your elders, mālama i ka ʻāina (to care for and live in harmony with the land) and what it means to live a pono or righteous life.

He also underscored the bond that speaking the same language creates, even when it seems you have nothing in common; if a person speaks with a dialect or uses a phrase that reminds you of home, familiarity is established and the wall between you shrinks.

“Language is important as a lens, but it also connects you to a base that goes back generations and generations that allowed the civilization to develop,” said Pila. Just as the high manifestations of language in song and poetry are important for a cultural identity, so are the low manifestations such as chatting on the porch with neighbors and making an effort to pronounce the Hawaiian words in your vocabulary correctly. The everydayness of people speaking to each other in their native tongue is necessary for the higher forms of language to have cultural resonance.

Another common misconception I realized I had given at least partial credence to was the impression that graduates from Hawaiian immersion schools were voting as a bloc in controversial disputes such as the TMT telescope on Mauna Kea and the stalemate over federal recognition. But Pila made the subtle point that the Hawaiian identity of students participating in immersion programs is very much intact, and so these students are less likely to need to rigorously defend what it means to be Hawaiian.

“If they are going to school in Hawaiian language the connection to language and culture is still very alive.” On the other hand, “…the person who is away from something tends to want to identify with it more than the person who has never been apart from it.” This exchange made me stop and question the public narrative that has linked pedagogy in Hawaiian immersion schools with the repatriation movement in Hawaiʻi, creating an unfairly weighted stereotype that immersion students are to blame for the recent protest movements in Hawaiʻi. Pila went on to give examples of the many and diverse paths that graduates of Hawaiian immersion schools follow, from doctors to construction contractors, policy advocates to artists.

“It is not a monolithic group,” he emphasized. Students represent a wide spectrum of political ideologies including opposing sides of well-known Hawaiian issues. They are not taught what to think but they are taught, partly by the very existence of the immersion schools, “…to be engaged and given a sense of agency.”

Some of the explanation for the modern or Western-leaning pursuits of immersion graduates is reflected in the constant evolution of language itself: “Language changes and culture changes, and even if you revive a language, you are not going to have the same culture that existed ages ago. It’s always changing.”

In that way, graduates of immersion schools are armed with the tools for success in any career path of their choosing, from livelihoods that seem more traditional, such as farming or navigating, to working in a laboratory or reading for the bar. Most of all, they are instilled with a curiosity for the world around them and a desire to participate.

In my family and the vast majority of other families in Hawaiʻi, there is a story of the blending and sharing of cultures where everyone seems to be mixed blood or hapa. I mentioned to Pila that I felt uncomfortable only celebrating the ancestry of one of my grandparents while neglecting my proud Portuguese and Chinese grandmothers and he warmly agreed: “It’s not Hawaiian to ignore the other cultures that have long been a part of Hawaii.”

Pila detailed how ʻAha Pūnana Leo has been experimenting with the layering of languages whereby students can learn to read and write Hawaiian by using kanji characters (characters used in Japanese and Chinese writing). And as complex as that initially sounded to me, it’s also an ingenious way to pay tribute to the blended ancestry that is typical in the islands. As he explained: “You cannot look at things, even language, in isolation. They need to be placed in context to be relevant. That is why learning Hawaiian through the lens of Japanese characters can be more of a reflection of the localness of Hawaii. In this way you’re not denying part of your background, you are building onto it.”

In response to my challenge that learning Hawaiian as a language has felt to me like an all or nothing endeavor – either you spend your formative years in immersion and develop a mastery or you are hopelessly limited to a handful of Hawaiian words and don’t know where to start, Pila was quick to respond saying: “You don’t have to do full immersion to add onto your knowledge of Hawaiian. Practicing hula, making music, celebrating the culture. Everyone can play a different role and we are probably stronger playing diverse roles in the revitalization … the most important thing is to preserve what we have and add onto that. Stay conscious, keep interacting with the language.”

The best place to start, recommends Pila, is close to home: “Connect to your family first. Ask them about Hawaiian words.” And in so doing, he said, you will ground the learning of Hawaiian language in your own personal story.

Since the day of our conversation, I have had Pila’s wise and earnest words returning to me again and again. I see now that I can weave my Hawaiian consciousness into the other areas of my life. I don’t need to be in Hawaiʻi, working for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, to be Hawaiian. I can carry it with me. Whether I’m living in Mexico City or negotiating trade policy, my perspective will always be influenced by the lessons of my elders and the place I come from.

The author with her kanaka grandpa

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.