Ten years ago, when John “Ahni” Schertow launched the award-winning magazine Intercontinental Cry, about 50 Indigenous Nations led their own front-line struggles to save some of the last intact habitats on Earth from the ravages of modern industrial development. Now more than 500 such struggles are raging around the globe. You’d never know it, even if you were a dedicated reader of mainstream and alternative media – unless one of those publications happened to be Intercontinental Cry. IC has had a hand in bringing some of those struggles to the international stage, most notably with the publication of the crucial essay by First Nations writer and activist Russell Diabo, which played a vital role in helping to spark the Idle No More movement. Diabo was the first to fully expose Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s plan to terminate First Nations treaty rights, and the world first learned about it at IC.

Ten years ago, when John “Ahni” Schertow launched the award-winning magazine Intercontinental Cry, about 50 Indigenous Nations led their own front-line struggles to save some of the last intact habitats on Earth from the ravages of modern industrial development. Now more than 500 such struggles are raging around the globe. You’d never know it, even if you were a dedicated reader of mainstream and alternative media – unless one of those publications happened to be Intercontinental Cry. IC has had a hand in bringing some of those struggles to the international stage, most notably with the publication of the crucial essay by First Nations writer and activist Russell Diabo, which played a vital role in helping to spark the Idle No More movement. Diabo was the first to fully expose Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s plan to terminate First Nations treaty rights, and the world first learned about it at IC.

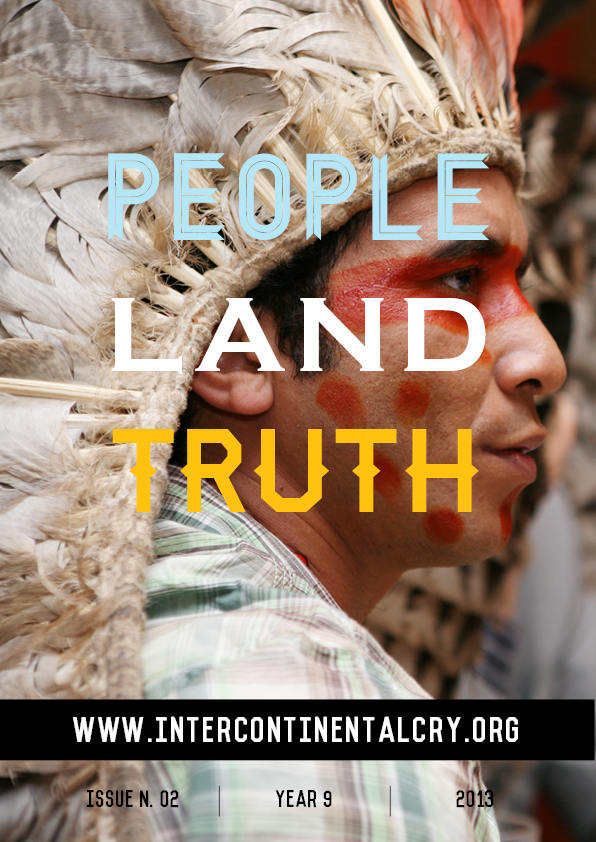

Schertow, from his bunker in a home office in Winnipeg, Manitoba, has taken up residence on those front lines, watching as the global indigenous movement has grown exponentially. He’s dedicated himself to telling the stories and to building a worldwide network of indigenous and non-indigenous reporters to serve as his eyes and ears. On any given day, he might be editing an eye-opening article from a writer in a far-flung land like the Philippines or Papua New Guinea; or investigating a fracking project threatening to contaminate the waters of an indigenous community in Canada or Botswana; or editing and designing the annual best-of collection, People Land Truth. How he does it all without a paid staff, a newsroom or even a journalism degree is worth a story in itself.

Truthout contributor Tracy L. Barnett took advantage of IC’s tenth anniversary to ask him a few questions.

Tracy Barnett for Truthout: Let’s start with your personal background. Where and how did you grow up, and how did that play into the journalist you are today?

I was born in the city of Winnipeg, quite a ways away from Mohawk territory. You might say I was a poster boy for neglected children, since I spent most of my youth wandering around drag strips, gas stations and the like. I actually grew up in a fairly anti-social and amoral environment. About the only lesson I was taught back then was that I was an emotional and psychological punching bag for almost everyone that mattered to me and I was powerless to stop it.

In my teens I developed a strong interest in poetry, which might’ve been my saving grace. I didn’t have much of a vocabulary back then – I mean, I wasn’t learning anything in school, so I started studying a dictionary. About four months after that I wrote and illustrated a small book of poetry that caught the attention of my English teacher. She was so impressed by my book that I never saw it again!

A few years later I rebelled with a vengeance. I dropped out of high school, rejected Catholicism and immersed myself in music, politics, poetry and art and alcohol and drugs. You might say that these were the first steps in my personal decolonization project, although I still had a very long way to go.

What inspired your decision to claim and embrace your indigenous identity?

It wasn’t until I met my two mentors and agreed to quit drinking and drugs that I was finally able to put things into perspective and come to terms with myself as a Mohawk breed and as a Two Spirit. It was sort of like someone turned the power on for the first time. Not only did they teach me every lesson I never had, they offered me the cultural foundation I always needed and showed me how to stand on it by example. They enabled me in all the ways that count. I was very fortunate in this respect.

What was it that inspired you to start the magazine?

I started IC just a couple days after walking away from a big political project I was working on at the time. I had this idea of creating an international confederacy of Indigenous Nations and an independent indigenous economy that would stand outside the capital system. I thought it was urgently needed, but after talking to the late Mohawk activist Dacajeweiah “Splitting the Sky” who started the League of Indigenous Sovereign Nations some years earlier, it became clear that the foundation was already in place. I still wanted to move forward with the economy, but around that time the group I was working with became obsessed with the fringe politics of the so-called sovereigntist movement. I tried to reason with them, to get back to the core vision, but they just weren’t interested, so I walked away. As soon as I did that, it occurred to me that I could work on something that was almost as important: informing the international community.

In 10 years of publishing Intercontinental Cry, what have been the highlights?

Back in 2010, we published a story about PetroWorth Resources’ fracking plans an arms stretch away from a Mi’kmaq community in Nova Scotia. At the time, this story was just starting to make headlines, which was great; but there was one thing missing in all that coverage: the Mi’kmaq! We put together a pretty good story that set the record straight. A few months after that, we covered the Kainai struggle against fracking in southern Alberta. That story rolled out a full six months before any other media picked up on it.

The Palawan’s recent victory against mining and oil palm development in the Philippines was another good moment for us. For quite some time, we were the only group outside of the Philippines to cover the Palawan’s struggle. Of course, that all changed when the highly successful “No to Mining in Palawan” campaign was launched; nevertheless, for almost a year we documented the Palawan’s efforts to protect their lands when others wouldn’t even so much as send out a tweet.

We were also the first to expose the Citizens Equal Rights Alliance’s 2013 launch of an ongoing national offensive that’s aimed at terminating American Indian treaty rights in the US. As well, we provided ground-breaking coverage on the convergence of Wall Street and the Tea Party in the political battle against Coast Salish First Nations defending the fisheries of the San Juan and Gulf Islands, which are threatened to become one of the world’s major carbon corridors.

What have been the biggest challenges you’ve had to face?

Fundraising, for one, has been extremely difficult. A lot of people think we have big money because we’re in Canada and because of the sheer strength of our investigative work, but we really don’t. I mean, we can’t even afford to get a bank account!

Keeping up with the news has been another big challenge. There was a time when I could cover all the major stories on my own, but those days are long gone – and it’s been very tough finding strong and credible writers to help cover everything, especially on a volunteer basis. We’ve had to turn a blind eye to a lot of important stories.

What have you learned along the way?

I never went to university or received any kind of training as a journalist, editor, or web designer so I’ve had to figure everything out on-the-fly. In that sense, IC has served as a kind of university for me. It’s been a constant challenge – but it’s one that I’ve thoroughly enjoyed.

In a broad brushstroke, what are some of the biggest challenges facing indigenous peoples today?

I would have to say it’s centered on building and maintaining a healthy relationship with Nation States that allows all Indigenous Nations to live in peace, without being constantly infringed upon, threatened, abused and extinguished. It’s the relationship so elegantly symbolized by the Kaswhenta or Two Row Wampum Treaty that the Confederacy signed withthe Dutch 400 years ago.

Ever since the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was passed, there has been a steady rise of governments considering sweeping legislation that targets Indigenous Rights. We’ve seen it in Canada, Australia, Brazil, Peru and a few other countries. We’ll see it in India soon enough. And we might see it in the US as well, given the recent court ruling that removed legal protections for the Indigenous population in Guam because those protections were “discriminatory.”

On the opposite side of the spectrum, there is a much larger rise in the number of Indigenous Peoples who are striving to quite literally defend the Earth. When I first started IC there were about 50 Indigenous Nations leading their own front-line struggles. Now there are easily more than 500.

Who has really inspired you over the years?

I’m continuously inspired by all the Indigenous communities that are stepping forward to reclaim their lands, revitalize their cultures and languages and re-establish themselves as self-sufficient Nations. I don’t know of anything more inspiring than that. I also draw a lot of inspiration and strength from people who lead by example and who tell it like it is, like Taiaiake Alfred, Evon Peter, Leanne Simpson and Russell Diabo.

What have been the hardest stories to cover?

We regularly face an uphill battle. We can’t exactly afford to send someone to Kenya to find out what’s happening to the Samburu or the Maasai. And we almost always have difficulty reaching people to get the bottom of something that might be happening. So, unless we happen to have someone on the ground to conduct interviews or someone from the community to document whatever might be happening, unfortunately our hands are tied.

With all challenges facing indigenous peoples today, what is there that gives you hope, that keeps you from despairing?

I consider myself to be a relentless optimist, but there are times when I’m filled with far more despair than hope, especially when I spend days working on different stories about grave human rights abuses while the media-at-large is obsessing over some silly spectacle; but, I press on anyway. I was taught that, as Kanienkehaka, Mohawk, I have a responsibility to serve the people. It’s always been my way, but now it keeps me going.

I also sincerely believe that, despite the constant stream of attacks and abuses and outright terror campaigns that so many Indigenous Peoples face today, we are going to overcome it. There’s just no question in my mind.

What is your goal for IC in the next 10 years?

I don’t know about the next ten years, but we have a big plan in motion to turn IC into a professionally run news service. Just last month we created a board of directors. Now we’re in the process of registering IC as a non-profit. Were also raising funds at Indiegogo so we can start offering more investigative pieces. Later, we plan to set up free media production workshops for Indigenous Peoples, offer a Spanish version of the site and among other things, host interdisciplinary gatherings, here in Winnipeg.

Why should non-indigenous people care about the stories you’re reporting? In a world where even the most caring can end up with a serious case of compassion fatigue, why should the average hardworking info-overloaded non-indigenous person take the time to read your publication?

We’re helping people stay on top of the efforts of the oldest and strongest movement in the world. On any given day, Indigenous communities are physically stopping mining companies from tearing apart biodiversity hotspots, preventing governments from enacting legislation that’s straight out of the 15th century and leading efforts to decommission hydro dams – all the while, fostering a global climate of political transparency and accountability. Suffice it to say, there’s a lot of insight and perspective to be gained from the work that Indigenous Peoples are doing, especially for those who are engaged in struggles of their own.

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.