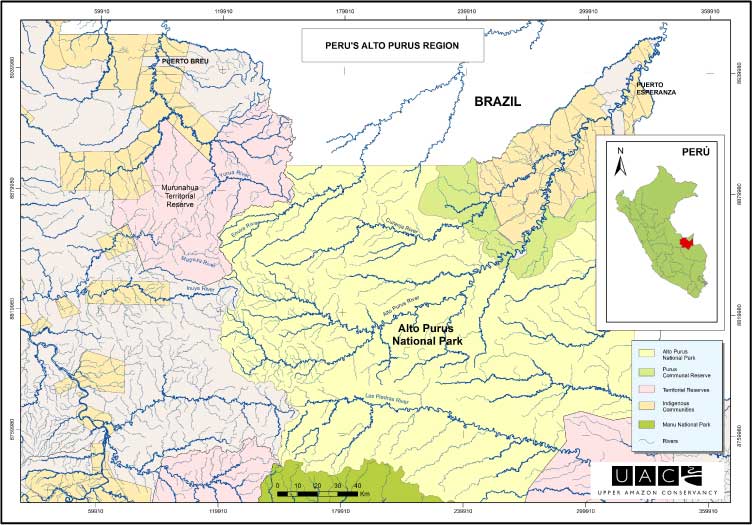

Cashinahua or Kashinawa (Kash- ‘bat’ or ‘cannibal’, nawa- ‘outsiders’) is the name commonly given to this group by other indigenous peoples living in Brazil and Peru along the waters of the Curanja and Purus rivers. However, their self designated name is Huni Kuin which means ‘real people’. The Huni Kuin speak hancha kuin – ‘real words’, a Panoan language, in the number of small settlements in which they live. Two thirds of Huni Kuin live in Brazil, mostly in Acre and the South of Amazonas state whilst a third hail from Peru, predominantly the state of Coronel Portillo. Population estimates vary greatly and taking both countries into account estimates range from 2,400 to 7,500.*

The Huni Kuin have a mixed subsistence economy that consists of hunting, fishing and gathering to supplement staples of Manioc and Plantain which they grow using swidden agricultural techniques. Villages, Mae kuin, are the main productive units and consist of a few extended families grouped matrilocally. However, despite the village autonomy, all Huni Kuin consider themselves bound to all others by the same name. They are known for their use of the powerfully hallucinogenic Liana plant and also as great artists, painting themselves and adorning many objects with designs and motifs of Kene Kuin- ‘true design.’

The Huni Kuin’s history since first contact has involved a great deal of hardship. Many were forced to migrate from their original home on the Envira river’s three affluents as early as the turn of the Twentieth Century, pressured and sometimes massacred by Brazilian rubber extractors in acts of organized violence to destroy ‘wild’ indians. The relationship between the Huni Kuin and forest prospectors seemed to improve in some cases around the 1940s when some began to seek contact and to offer their services working lumber and wild rubber. Unfortunately, poor treatment undermined this harmony and they broke off relations once more. Some Huni Kuin who were ‘tamed’ still bear the brands of their former ‘owners’ and today the real people still question their own logic in seeking contact. A handful became independent rubber trader or livestock owners for a time but most are no longer involved. Distrust for outsiders was further enhanced when the 1951 visit of an ethnographer was followed by a disease epidemic, wiping out a huge proportion of the population. Some groups did choose and maintain isolation from contact.

Today most still live in the villages they migrated to; though some have moved to cities such as Santa Rosa in Brazil. Alongside their traditional lifeways which the Huni Kuin staunchly defend they sell artifacts and forest goods to earn money and Western culture has been accepted in some forms. It is not uncommon to see the Huni Kuin use Western boats, tools or wear Western clothing. Brazilian groups tend to have been more greatly influenced in this respect.