San Antonio Necua, Baja California Sur, Mexico – Here in the binational Kumiai tribe’s largest community south of the U.S. Mexico border, a guided tour of the living medicine chest yields an abundance of traditional knowledge that centers on indigenous remedies and edibles.

The native herbal garden is a focal point for revitalizing the nearly lost traditions of the ethnic population of 6,000 that the Mexican government considers to be among the most in danger of extinction.

Nurtured by the women’s cooperative here since 2003, the medicinal plant project is the crowning glory of a community ecotourism venture that has received ample participation from non-governmental consultants, academia and authorities.

For its potential to strengthen the culture and serve as a bulwark against climate change disaster, it won the National Merit Award for Forestry in 2009 and went on to serve as a sustainable development model for the three other Kumiai villages located in Baja California.

Women’s cooperative member Leticia Arce guides tours of the garden, pointing out natural remedies and edibles, such as mint, rue, root beer plant, islaya cactus (for headache), valerian and chakpil (an aromatic), noting: “We reforest with local plants, which are used as medicine and food, to teach respect for them.”

In the Kumiai tribe’s largest community south of the U.S.-Mexico border, a guided tour of the living medicine chest yields traditional knowledge of indigenous remedies. Photo: Talli Nauman

Her colleague, Rosa Morales Dominguez, says that even the oak tree and its products are medicinal. “The oak is part of the culture. That is why it is a protected species. It provides food, shade and strength. We do not allow any damage. We try to protect it,” she says.

The oak, called shinau in Kumiai, is actually central to and emblematic of the culture. Among its many uses, it offers a bark that acts as an astringent to tighten gums around loose teeth.

At the center of San Antonio Necua stands a giant oak with wide-reaching branches, a venerable member of the species. The tree is the gathering point for annual ceremonies that reunite tribal members separated by the heavily guarded international border between Mexico and the United States.

Morales Domínguez says, the grandfather tree that hosts all this has “its roots so deep that they survive the statewide drought.”

The festivities feature singing and dancing with gourd rattles to honor nature, as well as a hockey-like game called piak, and, of course, feasting and a crafts fair complete with jewelry carved from the nutty seeds of the oak — acorns.

Although, San Antonio Necua offers scant diversity in tree species, the community never cuts down an oak tree for firewood, settling instead for fuel from a scraggly bush. “Only manzanita wood is used,” Morales says.

She and the other matriarchs of the village keep alive the custom of preparing a restorative porridge of acorn meal, central to the protein needs for the gut to help the body resist disease. It is no small undertaking.

Every November-December harvest season, they collect the nuts and grind hard nutmeats by hand; sift the meal, wash, rinse, drain, and dry it to make it palatable as what they call atole.

They named their ecotourism project Siñaw Kuatay, which means Big Acorn in the Kumiai dialect of the Yuman language they share with other tribes of the California border region. The project logo is … an acorn, the Kumiai symbol of regeneration.

Cabins, campsites, horseback rides, hiking, biking, water sports, cooking classes, a museum, a gift shop, and the natural medicine cabinet attract visitors whose spending helps the community restore the balance of nature and develop pride in age-old wisdom.

A museum , interpretive trails and classes attract about 400 students and tourists a month, making the project a model for other indigenous communities. Photo:Talli Nauman

The Kumiai can trace their origins in this area back 12,000 years. Every winter solstice, their culture recognizes the sun’s share of the day beginning to grow and the return of its lifegiving energy to the wild foods and domestic crops that provide good health and livelihood.

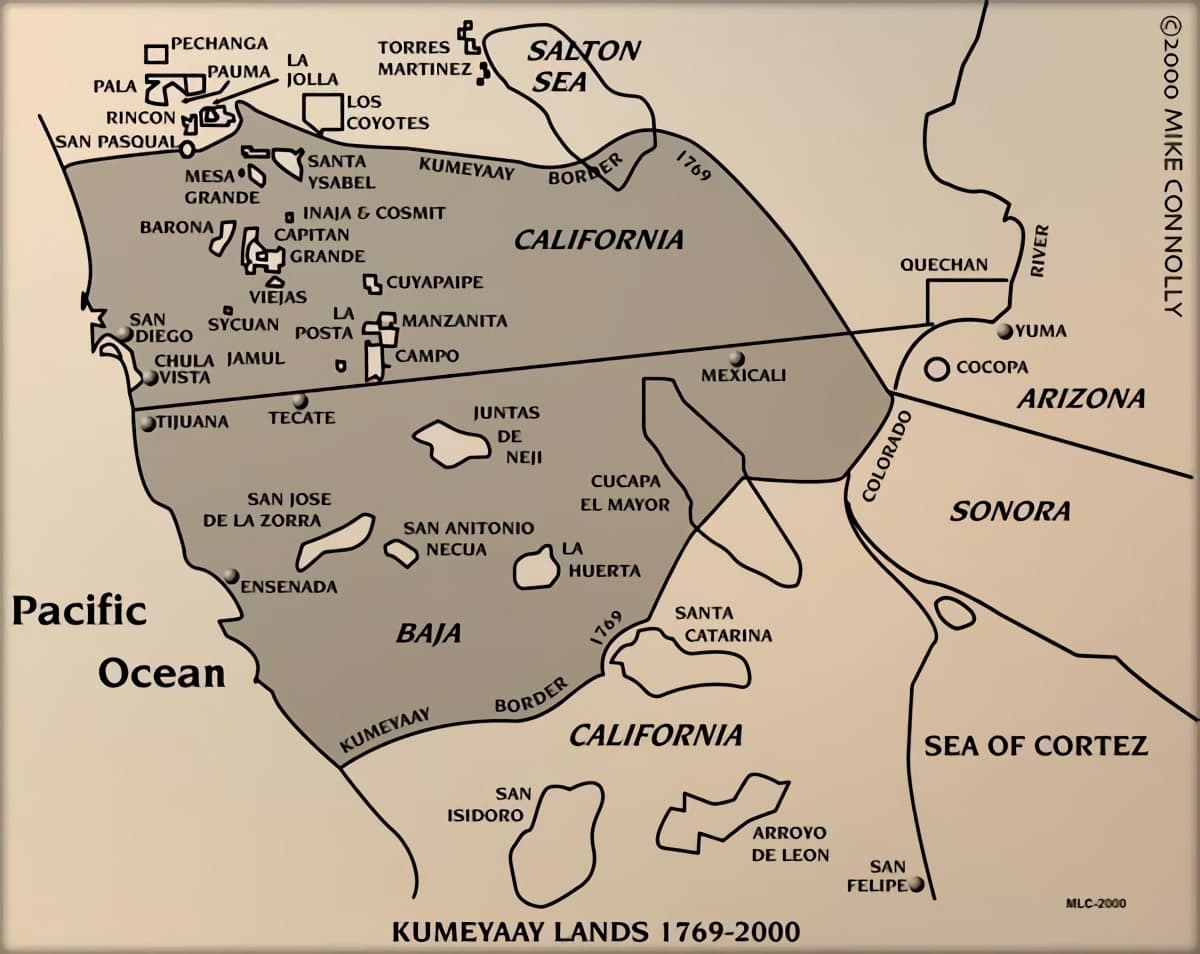

With only about 250 community members at San Antonio Necua and just 6,000 Kumiai between the entirety of the four Kumiai settlements in Baja California and the 13 in San Diego County, California, the Siñaw Kuatay Ecotourism Center is a matter of genetic and cultural survival.

To support the project, non-governmental organizations, including Terra Peninsular A.C., Instituto de Culturas Nativas de Baja California A.C., and Consultaría Vida Silvestre de México provided workshops framing community needs and aspirations.

The federal government’s National Commission for Indigenous Community Development pitched in for a museum, amphitheater, plumbing facilities and fencing.

The National Forestry Commission provided training in business management, ecotourism, and guide services, as well as a group shelter, nature trail, campground, barbeque grills, and garden installations. Agency personnel helped draw up and register organizational bylaws.

Cabin and campsite rentals bring in money to help the community restore the balance of nature and develop pride in age-old wisdom. Photo: Talli Nauman

With some 400 visitors arriving every month, participants and contributors consider the project an achievement in elevating appreciation for cultural heritage, recuperating cultural identity and promoting cultural exchange.

Meanwhile, they claim, they are raising environmental awareness, encouraging conservation of native species among locals and tourists alike.

Because of the center’s success, the project is being replicated in the indigenous Pai Pai Mission of Santa Catarina and the Kumiai village of La Huerta.

Among principle visitors arrive scientists and students, such as Marco Antonio Cardoza Beltran, who wrote a study called “Some Medicinal Plants of the Kumiai Indigenous Community of Northern Baja California” for his diploma at the non-profit Comunidad de Tlahui-Educa, a longstanding Mexican center for research in traditional medicine.

Cardoza’s compendium includes pictures taken here, such as that of the bark from the Quercus ilex, or oak tree, which is cut with a machete and chewed until the gums are numb to tighten them around teeth.

Cardoza cites Euphorbia prostrata Aiton, commonly known in Mexico as golondrina and called mat jnak in Kumiai. His description echoes cooperative member Arce’s. The leaves are brewed as a tea and used in drops for eye irritations, they say.

The Kumiai are also known to use this low-growing spurge to make a topical wash to relieve snake and bug bites, skin problems and unpleasant odors, according to The Mexican Atlas of Traditional Medicine Plants.

Similar in its Kumiai name of mat nak is the Anemopsis californica, an endemic flowering perennial known as lizard tail in English and yerba mansa in Spanish. This short-stemmed plant has big leaves with little pink or white rose-like blossoms.

According to some studies, it serves as a treatment for bleeding hemorrhoids due to its contents of flavonoids, phenolics and phenolic acid. Commonly used for relieving symptoms of cold and flu, it is recommended for preparation and consumption as a hot tea.

The Kumiai use the Sambucus nigra, or pshally, to stimulate perspiration and as a diuretic in detoxification treatments. Known as sauco in Mexico, its English name is black elderberry.

After the bunches of white flowers are picked off their bushes in May or June, two teaspoons of fresh or dried blossoms are steeped in a cup of hot water for use three times a day.

The Siñaw Kuatay botanical garden boasts Rosmarinus oficinalis, or rosemary, known as romero in promoting relaxation, and purification. Now they are finding it has a plethora of other medicinal uses.

Marrubium vulgarae, or white horehound is another favorite. Having been transplanted from across the Atlantic, it received the Kumiai name of melcupis. Its stem, leaves, and flowers all go into the pot for tea to counteract digestive discomfort.

It is also utilized widely for everything from combatting diabetes to respiratory problems, from hormonal reproductive imbalances to weight loss aid, from hernias to heart disorders, and from cancer to sprains, according to The Mexican Atlas of Traditional Medicine Plants.

Kujua, found in the garden at San Antonio Necua, is Cestrum auriculatum, or jessamine in English and hierba santa in Spanish. It’s a bush with branches that work for tea to counter chills and poultices for bruises.

Another in the herbal medicine cabinet here is Valeriana oficialis, which is jmilj in Kumiai, valeriana in Spanish, and valerian in English. Used mainly against insomnia, a tea of its flowers also can calm nerves, relieve cardiac conditions and soothe upset stomachs.

The Olea europea l., or olive tree, has earned the Kumiai name of noor pshiu since its transplant from the Mediterranean to the Guadalupe Valley at the doorstep of San Antonio Necua. The leaves are put to use in tea to lower blood cholesterol.

The leaves of the cottonwood tree, or Populus alba, are steeped in hot water to soak poultices for application to injuries and bug bite. The steeped concoction can be used as eye drops, and the leaves also can be applied directly to the temple in cases of headache.

The mint plant, Mentha spicata L., or hierba buena, is an analgesic that soothes the nerves, digestion and cold symptoms when its leaves are consumed in tea.

The resin of the Pistacia lentiscus has antibacterial and antifungal properties that Mediterranean people have valued for thousands of years in the treatment of gastrointestinal ailments. But here it is the leaves of the tall bush that are put to use, boiled for a drink and a cleanse; to aid in birthing.

To fight intestinal parasites in both humans and animals, the Kumiai use epazote tea made from Chenopodium ambrosioides, which some people call wormseed and others call Mexican tea.

Menstrual cramps, colds and eye infections all get treated with a tea made from a flower of the aster family, Matricaria chamomilla, aka chamomile.

A couple spoons full of the dried flowers from the plant known in Mexico as gordolobo, or mullein, works wonders on respiratory disorders ranging from asthma to colds. The scientific name is Verbascum thapsus.

For kidney pain, diabetes, and stomach ache, the Kumiai historically resort to Ephedra, known as Mormon Tea in the United States, and canutillo in Mexico. Additionally, the tea from its stalks is a decongestant commonly substituted with a synthetic medication in commercial cold medicines.

The baccharis glutinosa, or saltmarsh baccharis, called guatamote in Mexico, has proven to be anti-bacterial, as well as having properties for treating gynecological concerns, and even hair loss prevention.

Cardoza’s study adviser Mario Rojas Alba notes that many of the species in use are not endemic, yet the small collection studied serves as an introduction to the local use of medicinal plants.

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.