Having already devastated Sumatra and Borneo, Indonesia’s plantation industry is aggressively breaking new frontiers, moving to the less-developed eastern provinces and looking for land on smaller islands. The companies connive with local leaders to move in stealthily. Indigenous inhabitants receive no information other than sweet promises of development; only when the bulldozers move in do they realize that they have been robbed of the forest that gave them their livelihood and their identity.

That could have been the fate of the Aru Islands, a low-lying archipelago situated some 200km south of West Papua in the Arafura sea. Since 2007, a plantation company had been scheming to take over more than three-quarters of the Indigenous islanders’ ancestral land. No one ever fully woke up to the gravity of the threat until about a year ago, when the Aru Islanders realized that action was needed. Since then, they have been united in defiance, building an impressive and diverse movement to defend the land they call Jargaria.

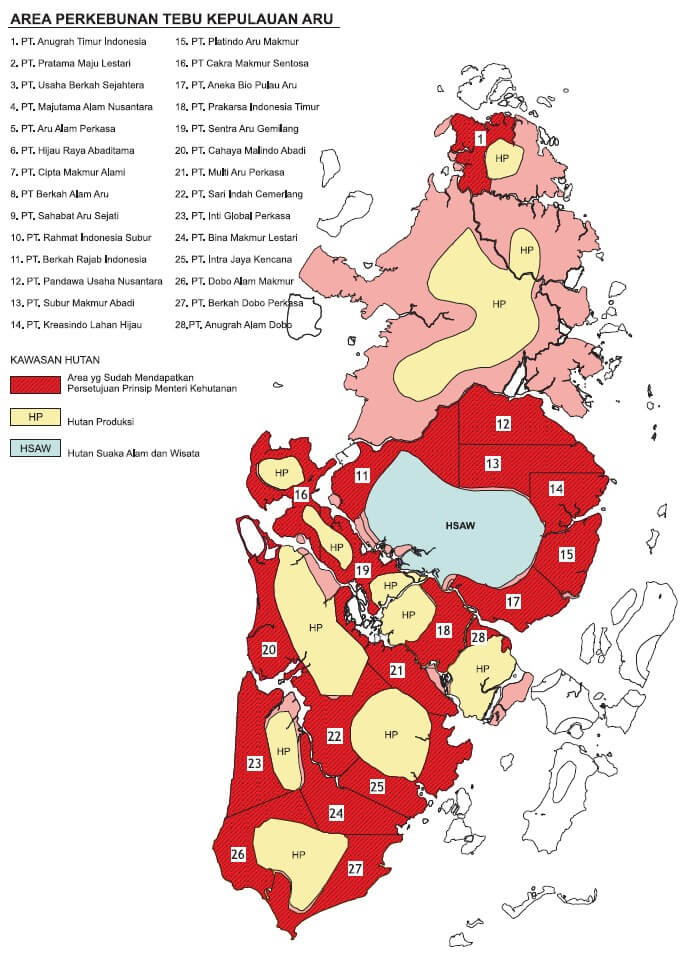

The Menara Group’s own map of its proposed sugar plantation. Local leaders gave them permits for the whole area marked in red and pink, nearly 500,000 hectares

The Menara Group, the company which dared to venture onto the soil of Jargaria, is a newcomer to the plantations game. The company, almost unknown and highly secretive, had an ambitious plan to cover 484,000 hectares with sugar-cane. That would consume most of the Aru Archipelago, whose total land surface is 629,000 hectares. To understand the enormity of this plan, imagine one company acquiring the rights to land the size of Norfolk in the UK or Delaware in the US.

Now it appears that the islanders are on track for a cautious victory. Indonesia’s forestry minister backtracked on his ministry’s former support for the plantation, confirming that he would not sign the permit to release hundreds of thousands of hectares of state forest.

Menara Group had been coming up with various proposals in the area since 2007, before embarking on this sugar-cane plan in 2010, lobbying local and provincial leaders to amend the land-use plan and issue the required permits. It got them easily enough; although every stage of the process was riddled with irregularities, leading most people to suspect that a lot of the lobbying was done through backhanded deals. There is insufficient evidence to prosecute, however, Teddy Tengko, the local District Head who gave Menara Group its plantation permit, has since been removed from his post and convicted for receiving bribes in a different case.

The forestry minister’s statement was certainly welcomed, but local activists are aware that the story could be far from over.

Going off to hunt on the grasslands of Southern Aru

Aru is an ecologically rich land. The forest rings out with birdsong, from its most famous inhabitant the greater bird of paradise, as well as white and black cockatoo species and the colourful eclectus parrots. The indigenous mammalian fauna are marsupials, kangaroos and cuscuses, although deer and wild pigs were brought from further west in the canoe of some distant ancestor and are now also plentiful. The forest for the most part escaped the ravages of the logging industry that swept through Indonesia in recent decades, and large ironwood trees grow abundantly. The surrounding Arafura sea teems with fish, and is well known as Indonesia’s richest fishing ground, with ships both legal and illegal coming from far away to reap a share of the harvest.

Indigenous villages are scattered around the coast, rivers and channels that dissect the archipelago into a jigsaw of islands; their inhabitants are generally able to live comfortably from this land. The subsistence food is the sago palm, which grows in abundance in the forest. Forest gardens provide fruits, vegetables and yams. Protein is also usually not a problem. One morning in Hokmar village a group of adults and children caught small fish from the village jetty using unbaited hooks. Pulling out a couple every minute, within ten minutes, one person caught enough to feed his family that day. Another day it could be shellfish gathered from the mangroves, or deer or kangaroo meat hunted from the forest.

A hunter carries home a kangaroo caught in the forest

The environment also provides many opportunities for autonomous income generation, from farming coconuts to be dried and sold as copra for their oil, collecting pearls and valuable sea-cucumbers from the sea-floor, or swiftlet nests from cave ceilings, setting lobster pots to catch lobsters and crabs for the international restaurant market (a 1kg live crab is bought for 100,000 rupiah by local traders), felling selected trees to be sold locally for construction, or hunting deer for their meat.

This is an important reason why local people have been so determined to resist PT Menara Group’s plan – although not rich, they live amidst relative abundance. There is no conceivable way they would be better off as plantation labourers, receiving the local minimum wage of 1,400,000 Rupiah per month ($125), out of which they would have to buy all their food because the forests are gone and the seas polluted.

Of course, the forest is more than a mere economic resource, together with the ocean it is what gives the Aru people their identity. For example, every year at the end of the dry season in the South of Aru, twelve different villages come together in a celebratory ritual and burn the areas of grassland which are interspersed with the thick forest. As deer and pigs run from the fire, hunters are ready with their bows and arrows. In this way, people get to feast, community bonds are strengthened, the ancestors are remembered and the grassland ecosystem is maintained, ensuring a valuable diversity of habitats.

According to Yusuf Gaelagoy from Marafenfen village “Every year, every season, we have to burn the grasslands. It is a tradition from long ago, from our ancestors, and we keep it alive until the present day. Menara Group would say that the grasslands is wasteland which has no use whatsoever. However for us, the indigenous people here, it is the most important of all.”

A demonstration against the Menara Group in Dobo, the largest town in Aru

Local people were a little slow to realize what was going on, but eventually the enormity of the plans sunk in: this one plantation could signal the annihilation of their entire homeland. In mid-2013, local young people discussed the situation with village elders and the local indigenous people’s organization. After agreeing that they had to fight the plan, the Coalition of Youth and Indigenous People of Aru was set up.

Many were motivated to join this new movement. Young people hitched rides on local boats or put their money together to buy fuel to travel round affected villages discussing the problem. In almost every village they reached, once people knew about the plan, opposition was overwhelming, and nearly every village head in the archipelago was happy to sign a statement of opposition to Menara Group and similar companies. Several demonstrations were also held in the main town Dobo to raise consciousness there. Women traders in the local market helped spread the word about the demos, aware that everything they sold was brought from their villages which are now under threat from the plantation.

The Maluku Protestant Church, responding to the concerns of its congregation, has also thrown its weight behind the struggle, and clergy are educating the people about what the likely effects of a sugar-cane plantation would be. Because there is a parish in most villages, this church has a unique network to spread the message about this issue. The Maluku Protestant Church also passed a motion in its Synod to support the struggle in Aru, and so now the whole church infrastructure provides practical support, for example, sending trainee priests with activist inclinations to work in Aru. Muslim and Catholic young people are also involved in the coalition.

Several villages have invoked the tradition of ‘sasi’, which is a traditional form of prohibition. In this case, outsiders from companies are prohibited from trespassing on ancestral land. A sign is given by affixing dry coconut branches to treetops, or planting them in the ground. People believe that nature will cause some misfortune to fall upon those who disregard the sasi – it could be a snake-bite, or they might get lost, or not find the land in the first place.

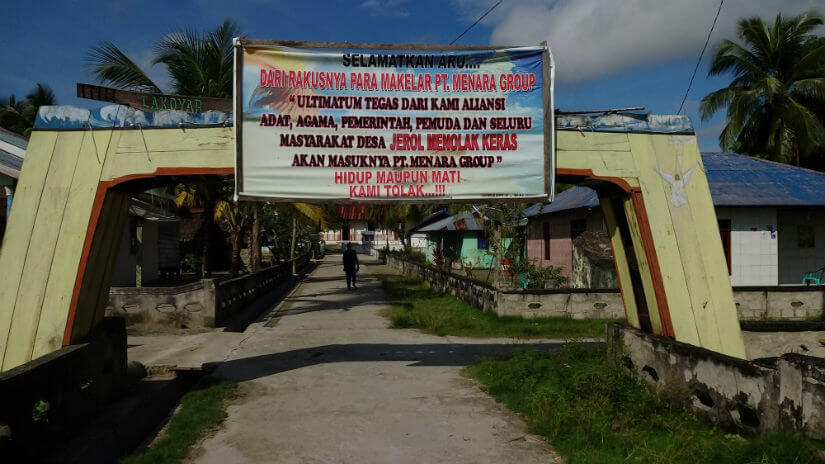

If all else fails, people from several villages have indicated that they are prepared to do whatever it takes to defend their land. If Menara Group or another company moves in, they will be ready with their bows and arrows.

A banner rejecting the sugar-cane plantation in Jerol Village. Translation: Save Aru from the greed of the Menara Group profiteers. “The clear ultimatum from our alliance of indigenous people, religious groups, government, youth and the whole population of Jerol village is that we strongly oppose Menara Group moving onto our land” Alive or dead we oppose them

One of the movement’s greatest strengths is that popular opposition is not only limited to Aru. After a group of indigenous elders visited the provincial capital Ambon in September 2013, they found many people that were eager to support their resistance. Local activists there came up with a two-pronged strategy to give visibility to the struggle: offline and online. Offline meant cultural action – street performances, discussions, music shows, hip-hop songs, poetry compilations, all mobilizing the youth of Ambon in solidarity. Online, a compelling website and astute use of Twitter meant that within a couple of days, people throughout Indonesia and around the world were aware of the Menara Group’s plans.

In this way, the far-flung archipelago’s big headache quickly became a global concern, despite hardly being mentioned by any commercial media. Within Mauluku itself it became an especially hot topic. This helped in triggering wider scrutiny of the company, and people in Aru found strength in a feeling that the world was behind them in their struggle.

A banner made of solidarity messages sent from around the world on social media is displayed in Dobo

An infographic produced by the campaign illustrates how much of Aru would be lost to the plantation company

With the increased attention, it became obvious that proper procedures had not been followed at any stage of the permit process. The whole deal reeked of corruption, and eventually the newly-elected Provincial Governor and a national monitoring unit appointed by the President said they would look into how the company got its permits.

In the end, the forestry minister, backtracking on the previous in-principle permit handed out by his ministry, said that a study team had just found that the land was not suitable for sugar-cane after all. Too hilly, he told the media. The stated reason may seem like grasping for any plausible excuse to cover one’s back, but it meant he would not be signing the final permission the company needed.

So it is good news for the Aru Islanders. However, so far there are only media reports to go on, no concrete action. Other permits the company obtained at the local and provincial levels have not been canceled. And as Indonesia is in the middle of a general election, there will be a new forestry minister within a few months. Menara Group may yet survive. It is a very well connected company; its chairman, D’ai Bachtiar, is the former head of Indonesia’s police force and ambassador to Malaysia.

However, the biggest concern at the moment is what will happen next if the Menara Group’s plan is canceled, as it presently seems. One of the Menara Group’s first steps was to lobby for a change in the land-use plan, which now allows 500,000 hectares of forest to be converted to plantations. There are plenty of companies eyeballing that land, most likely to plant oil palm. The valuable timber in these primary forests alone is a big attraction to any potential investor.

One of these companies is the Nusa Ina Group. This company, which has already ravaged the north coast of Seram island with its oil palm plantations, also hoped for a large concession in Aru back in 2010; however, it was outbid by Menara Group. For some time, it has been anticipating a post-Menara Group scenario, courting Indigenous elders with some subtlety by paying for indigenous council assemblies and flying leaders to Jakarta. The campaign to Save Aru has not bothered too much about these activities; however, with the Menara Group seemingly out of the way, Nusa Ina may be poised to make some bigger moves; that is, unless the campaign to Save Aru can stop them.

The biggest challenge now is whether or not everyone can build on the momentum in Aru to secure the land of Jargaria for the long term, so that future local leaders can not be tempted by more lucrative offers from plantation companies that will only bring misery for local people.

Meanwhile, activists in the area also express the hope that the energy and creativity of the struggle to save Aru will motivate Indigenous Peoples on other nearby islands – where plantation companies are also gearing up to take over hundreds of thousands of hectares – to step up and take control of their own future instead of becoming the next victims of development.

To learn more visit: www.savearuisland.com

Selwyn Moran researches and translates news from social movements across

Indonesia, and especially West Papua. He maintains the blog awasMIFEE

(awasmifee.potager.org) which focusses on plantations and other threats from top-down development in West Papua.

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.