In early 2011, Protect Our Manoomin (Weweni Ganawendan Gi-Manoomininaan), an Ojibwe-Anishinaabe grassroots group in Minnesota, was established to raise awareness of the threats of sulfide mining on the ceded lands under the treaties of 1854 and 1855. The main focus of Protect Our Manoomin has been to educate and inform people about sulfide mining and its detrimental impact on the environment – particularly the impact on manoomin.

Healthy stand of manoominThe English word for manoomin is wild rice. However, the English translation doesn’t convey the deep meaning that manoomin has for Ojibwe-Anishinaabe people. Manoomin means “Good Berry.” Manoomin is rooted in Ojibwe-Anishinaabeg prophecies and origin stories. It is a special gift given to the Ojibwe-Anishinaabeg by Gichi-Manidoo (the Creator). Manoomin is the food that grows on water. Manoomin not only provides food and an economic base, it also provides a cultural, spiritual and ceremonial connection. To the Ojibwe-Anishinaabeg, manoomin is a living being that has been an inherent part of Ojibwe-Anishinaabe culture for nearly a thousand years.

Healthy stand of manoominThe English word for manoomin is wild rice. However, the English translation doesn’t convey the deep meaning that manoomin has for Ojibwe-Anishinaabe people. Manoomin means “Good Berry.” Manoomin is rooted in Ojibwe-Anishinaabeg prophecies and origin stories. It is a special gift given to the Ojibwe-Anishinaabeg by Gichi-Manidoo (the Creator). Manoomin is the food that grows on water. Manoomin not only provides food and an economic base, it also provides a cultural, spiritual and ceremonial connection. To the Ojibwe-Anishinaabeg, manoomin is a living being that has been an inherent part of Ojibwe-Anishinaabe culture for nearly a thousand years.

Damaged stand of manoominManoomin is also an environmental resource. Healthy stands of manoomin are the barometer of a healthy ecosystem. But sulfates, which are released through the sulfide mining process, enter into rivers and lakes. The sulfates drift into the sediment where they convert into hydrogen sulfide that enters the root system of manoomin. Concentrations of sulfates that are over 10 parts per million of sulfate impairs the growth of manoomin resulting in withered leaves and smaller seeds; high concentrations of sulfates suffocate and kill manoomin. Macroinvertebrates, vegetation, flora, fish, waterfowl, and wildlife are impacted. Additionally, sulfate-reducing bacteria transforms into methyl mercury that leads to mercury fish contamination. Minnesota state law limits sulfate to 10 parts per million to protect manoomin. The extractive resource colonies proposed for northern and central Minnesota will exceed the limits of the law.

Damaged stand of manoominManoomin is also an environmental resource. Healthy stands of manoomin are the barometer of a healthy ecosystem. But sulfates, which are released through the sulfide mining process, enter into rivers and lakes. The sulfates drift into the sediment where they convert into hydrogen sulfide that enters the root system of manoomin. Concentrations of sulfates that are over 10 parts per million of sulfate impairs the growth of manoomin resulting in withered leaves and smaller seeds; high concentrations of sulfates suffocate and kill manoomin. Macroinvertebrates, vegetation, flora, fish, waterfowl, and wildlife are impacted. Additionally, sulfate-reducing bacteria transforms into methyl mercury that leads to mercury fish contamination. Minnesota state law limits sulfate to 10 parts per million to protect manoomin. The extractive resource colonies proposed for northern and central Minnesota will exceed the limits of the law.

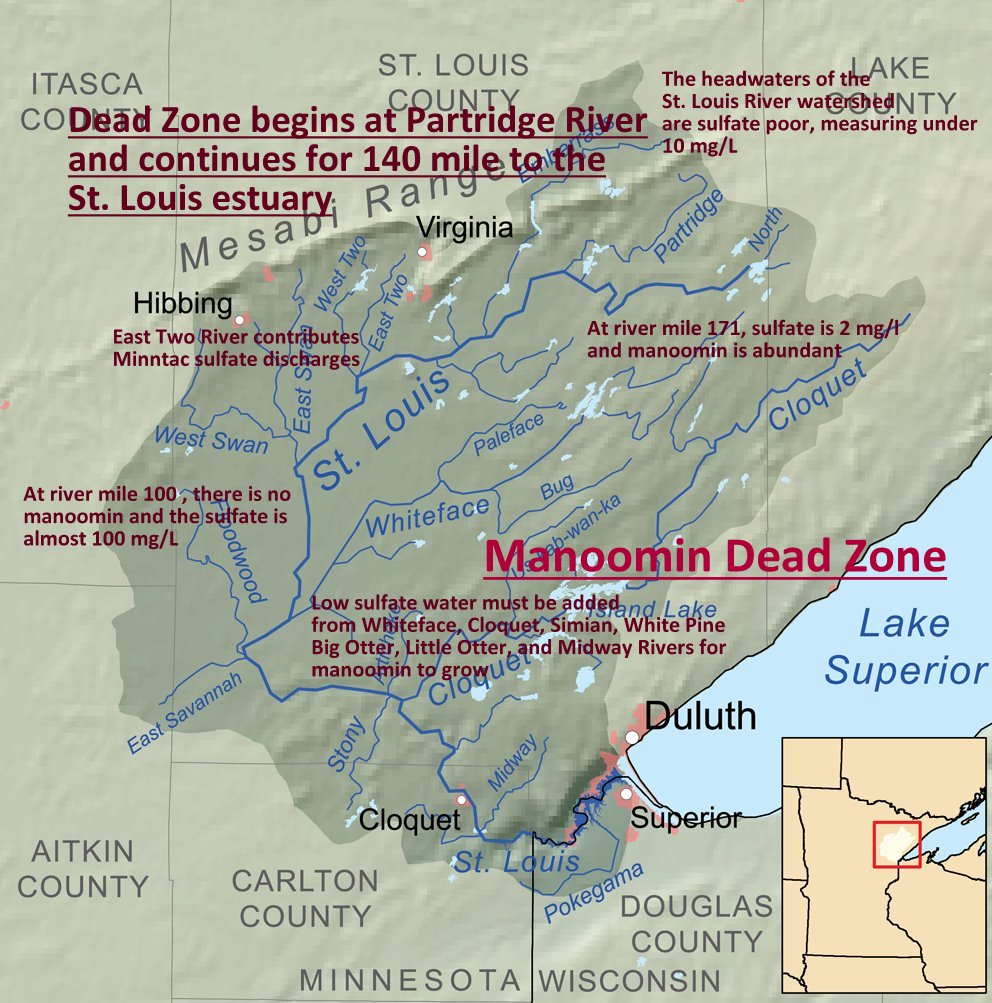

Wlid Rice Dead Zone on the St. Louis River.That sulfates can kill manoomin is evidenced by the Wild Rice Dead Zone – a stretch that begins where the Bine-ziibi (Partridge River) enters into Gichigamiwi-ziibi (St. Louis River) and extends 140 miles to the Anishinaabeg-Gichigami Maamawijiwan (Lake Superior Basin). The Wild Rice Dead Zone is the result of extremely high concentrations of sulfate released by U.S. Steel’s Keetac and Minntac taconite mines. Sulfide mining will add yet more sulfates into rivers and lakes thereby affecting the food that grows on water.

Wlid Rice Dead Zone on the St. Louis River.That sulfates can kill manoomin is evidenced by the Wild Rice Dead Zone – a stretch that begins where the Bine-ziibi (Partridge River) enters into Gichigamiwi-ziibi (St. Louis River) and extends 140 miles to the Anishinaabeg-Gichigami Maamawijiwan (Lake Superior Basin). The Wild Rice Dead Zone is the result of extremely high concentrations of sulfate released by U.S. Steel’s Keetac and Minntac taconite mines. Sulfide mining will add yet more sulfates into rivers and lakes thereby affecting the food that grows on water.

There is approximately 48,200 acreage of manoomin within the ceded lands of the 1854 and 1855 treaties. Thousands of acreage will be impacted by sulfide mining. The combined total of manoomin in 1854 and 1855 ceded lands account for over three-quarters of the estimated total 64,000 manoomin acreage in Minnesota. Under the treaties, the Anishinaabeg maintain usufructuary rights to hunt, fish, and gather manoomin. These usufructuary rights were affirmed by the Supreme Court decision – Minnesota v. Mille Lacs Band – in 1999. However, the issue of ceded lands has been marginalized by extractive resource colonies that seek to build mining districts within ceded lands.

The issue of sulfide mining is interwoven in the web of corporatism. Sulfide mining is about corporate greed, and profits made at the expense of the environment. The profit margin does not go back into local communities. Mining creates a boom and bust economy. Jobs for the local workforce are short-term and limited. The aging workforce on the Iron Range lacks the specialized, technical skills that require a minimum two-year college degree for a majority of the jobs.

In the case of PolyMet Mining, the profits go back to a Canadian extractive corporation and to Glencore Metals and Minerals, an international commodities conglomerate based in Switzerland. And the extracted copper will be exported to China.

How is it that foreign corporations are able to come into Minnesota, extract copper, and ship it overseas?

The answer is the legal fiction called corporate personhood that enables corporations, e.g., copper extractive resource corporations, to influence our state legislature through unlimited campaign contributions. Through a corporatist agenda, we have state legislators who are amending or rewriting laws for the benefit of extractive resource industries.

These revisions of laws undermine existing laws like Minnesota’s Wild Rice/Sulfate Water Quality Standard and the EPA’s Clean Water Act and Clean Air Act. And the extractive resource corporations can do this because Citizens United v. FEC has strengthened their status of “persons” with fundamental natural rights. Under that status, corporations, including foreign corporations, can make campaign expenditures, without limit, to influence candidates of their choice – in this case, influence pro-mining candidates who can further the sulfide mining agenda by passing laws that are favorable to copper extractive resource corporations like PolyMet Mining/Glencore Metals and Minerals, Kennecott Tamarack/Rio Tinto, Twin Metals/Antofagasta PLC, Cardero Resource Corp., and Teck Mining Corp, all of whom are planning to establish mining districts in Minnesota.

But the influence of corporate personhood goes beyond state legislators. It extends to congressional lawmakers in Washington. This is exampled by congressional lawmakers who are involved in efforts to weaken EPA standards for extractive resource corporations and thereby place our environment at risk for the benefit of economic gain.

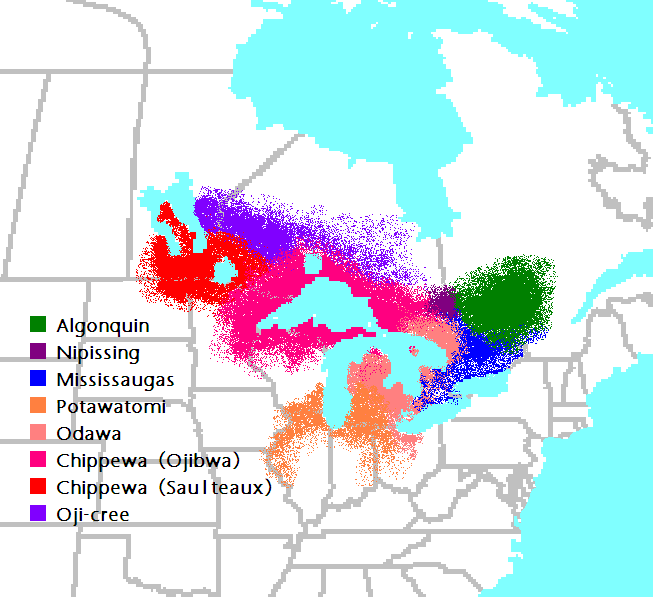

The Ojibwe-Anishinaabe people know about corporatism. It is part of Ojibwe-Anishinaabeg history. In the 1600s, the French came through Ojibwe-Anishinaabeg Akiing (Land of the Ojibwe-Anishinaabe that includes Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan) looking for copper deposits to exploit for economic gain. The Ojibwe-Anishinaabeg never revealed the locations of those deposits. In 1826, the U.S. negotiated a treaty at Nagaajiwanaang (Fond du Lac, Minnesota). The treaty was largely to identify the various Ojibwe-Anishinaabeg nations in Ojibwe-Anishinaabeg Akiing.

There was no cession of tribal land in the treaty of 1826. However, Article 3 of the treaty contained a provision that the U.S. had the right to search for, and carry away, any metals or minerals from any part of Ojibwe-Anishinaabe country. And further, the grant was not to affect the title of the land, nor the existing jurisdiction over it. Less than twenty years later, mining operations began in Michigan at Isle Royale and the Upper Peninsula.

There was no cession of tribal land in the treaty of 1826. However, Article 3 of the treaty contained a provision that the U.S. had the right to search for, and carry away, any metals or minerals from any part of Ojibwe-Anishinaabe country. And further, the grant was not to affect the title of the land, nor the existing jurisdiction over it. Less than twenty years later, mining operations began in Michigan at Isle Royale and the Upper Peninsula.

Later treaties weren’t just about the cession of tribal lands to open for settlers and farmers. The U.S. government’s main thrust focused on corporatism – the collusion of the government and extractive resource industries to exploit tribal ceded lands for economic gain and profit.

In the treaty making process, most tribes maintained a portion of their homelands, i.e., reservations, and ceded their outlying homelands. However, tribes maintained usufructuary rights, i.e., hunting, fishing, and gathering rights, on their ceded lands. For example, the Treaty of 1837 states: Article 5, “The privilege of hunting, fishing, and gathering the wild rice, upon the lands, the rivers and the lakes included in the territory ceded, is guaranteed to the Indians, during the pleasure of the President of the United States.”

Usufructuary rights were denied by the extractive resource companies who poured into ceded land to take the timber, metals, and minerals. And these rights were denied by the states because the ceded lands generated an economic base for the states.

It wasn’t until the 1970s that usufructuary rights began to be litigated in state courts and in the Supreme Court. In 1974, the Bolt Decision in Washington State set the precedent in recognizing usufructuary rights.

First evidence of Acid Mine Drainage (AMD) in Minnesota. The drainage is from a former mine at Ely, Minnesota The area of the AMD is located in the area of the proposed copper mines.What began with the treaties continues today under the banner of corporate personhood. And this time around, both Ojibwe-Anishinaabe and non-Natives are affected. Private land owners are affected. The environment is affected. The rights of human beings are affected because the so-called personhood rights of corporations take precedence over equal rights.

First evidence of Acid Mine Drainage (AMD) in Minnesota. The drainage is from a former mine at Ely, Minnesota The area of the AMD is located in the area of the proposed copper mines.What began with the treaties continues today under the banner of corporate personhood. And this time around, both Ojibwe-Anishinaabe and non-Natives are affected. Private land owners are affected. The environment is affected. The rights of human beings are affected because the so-called personhood rights of corporations take precedence over equal rights.

A fact sheet issued by Protect Our Manoomin cites the following information on the PolyMet mine:

(Sources – Protect Our Manoomin, WaterLegacy, Friends of the Boundary Waters Wilderness, Save Our Blue Sky Waters)

Despite PolyMet’s assurances of environmentally safe and responsible mining, the above facts attest to the deceit that PolyMet is willing to commit in presenting itself as a steward of the environment. In response, Protect Our Manoomin issued the following resolution regarding its position on safe and responsible mining.

Protect Our Manoomin supports environmentally safe and responsible mining if the following criterion is met:

In closing, Protect Our Manoomin has issued the following summation:

What we do today affects the generations that follow us. Corporate personhood isn’t concerned about the next generation that follows or future generations. Corporate personhood is about instant gratification for profits and economic gain. There is no concern about our nibi, our water, which is sacred and provides us with life. There is no concern about the impaired environment and the poisoned waters they will leave for their children and their children’s children. Indeed, if corporations are “persons,” then it can be said that their personhood personifies the dysfunctional behaviors of greed, bulliness, and intimidation to get what they want.

In the Anishinaabe mindset, we think in terms of the Seventh Generation. When we undertake any actions or make any decisions, we consider how our actions and decisions will affect the Seventh Generation from now. It is that mindset that we all need to help guide us in our opposition to corporate personhood and sulfide mining. What we do today, we do for the generations that follow.

E-Mail: r_desjarlait@protectourmanoomin.org

Website: http://www.protectourmanoomin.org

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/groups/protectourmanoomin

Robert DesJarlait is a Co-Founder of Protect Our Manoomin. He is from the Red Lake Ojibwe-Anishinaabe Nation. He is a free-lance journalist and his articles have been published in several Native news media.

Indigenous Peoples are putting their bodies on the line and it's our responsibility to make sure you know why. That takes time, expertise and resources - and we're up against a constant tide of misinformation and distorted coverage. By supporting IC you're empowering the kind of journalism we need, at the moment we need it most.